For someone who shuns the spotlight, chemicals billionaire Jim Ratcliffe has been in the news rather a lot lately.

Crowned Britain's richest person by the Sunday Times in May, knighted by the British Queen in June, he's now poised to quit the UK to live in Monaco, according to the Telegraph - sparking a fair bit of criticism given his support for Brexit.

This straight-talking runner, mountaineer and adventurer certainly likes to stay busy. He’s also developing a successor to the Land Rover Defender, a favourite of Britain’s moneyed rural classes, and merrily snapping up trophy assets such as the fashionable motorcycle jacket maker Belstaff, a Swiss football club and a safari park. There have been reports that he’d like to buy English Premier League Chelsea Football Club from Roman Abramovich.

Mr Ratcliffe, 65, can no doubt afford it. His globe-spanning chemicals empire Ineos generated $6.6 billion of earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (ebitda) in 2017 on sales of about $60bn, thanks to buoyant demand and ruthless cost control.

He’s worth about $14.5bn, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, based on his 60 per cent or so equity interest in Ineos and a couple of mega-yachts. That’s maybe a conservative calculation.

He’s a complicated character, though, and his Anglo-Swiss company is pretty opaque. Still, if you're wondering what it takes to become Britain's richest person, here’s how he did it.

Don't worry about being a late starter

Mr Ratcliffe, who studied chemical engineering and worked later in venture capital, only started as an entrepreneur in 1992, aged 40, and founded Ineos just 20 years ago. It expanded quickly by buying unfashionable petrochemical assets cast off by big oil and chemicals groups. By slashing fixed costs, he soon had most of them generating lots of cash, allowing him to refinance loans. Hiss trusted equity partners Andy Currie and John Reece each own almost one-fifth of Ineos.

Make friends with debt but don’t fall in love with it

One of Mr Ratcliffe’s big talents is persuading banks to lend him vast amounts of money against Ineos’s assets to use for more deals. Most important was the $9bn purchase of BP’s Innovene petrochemicals business in 2005, which made Ineos a big player in the industry. The financial crisis showed how risky that borrowing can be, though. Demand for chemicals crashed in 2008, Ineos tripped a debt covenant and its bonds crashed to about 10 cents on the dollar. Ineos lived to fight another day, but Mr Ratcliffe still resents the extra fees he had to pay to lenders. He seems to have learned his lesson. Net debt at the core group was more than $8bn in 2009, or seven times ebitda according to Bloomberg data, but that fell to below two times at the end of last year. It’s been able to pay out about €500 million (Dh2.07bn) in dividends during the past two years. No wonder Mr Ratcliffe’s been on a shopping spree.

New man at the helm for UK energy major seeking to fuel fracking boom

BP sells crucial oil pipeline in North Sea to Ineos

Never sell equity and definitely don't go public

Mr Ratcliffe once ran a public company (Inspec, which he sold in 1998) but seems to have no intention of doing so again. Public markets, he reckons, are too short-termist and don’t value cyclical and commodity chemicals properly. Selling equity is dumb if you don’t have to. “Once it’s gone you never get it back,” he says. Elon Musk would doubtless agree. Like the embattled Tesla chief, Mr Ratcliffe is dismissive of 20-something equity analysts (still “in short trousers”) and pretty averse to non-executive directors. Besides the three owners, Ineos has just one other board member. Some credit agencies flag this as a potential problem, alongside related-party transactions involving Ineos.

Keep it tight

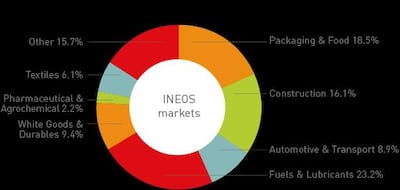

Think of Ineos as the anti-BASF. Unlike the bureaucratic German giant, Mr Ratcliffe’s Ineos empire is run by a small team of 40 people from a Knightsbridge headquarters. Power is devolved to the business units and managers given incentives to boost profits. For an outsider, however, keeping track of all the subsidiary companies is difficult. Ineos has almost 20,000 employees at more than 30 chemicals, oil and gas business units. This makes the finances very complicated, something that the trained accountants Mr Ratcliffe and Mr Reece appear to enjoy.

Don’t always be nice

Mr Ratcliffe is a divisive figure, admired for his business nous but disliked by many trade unionists and environmentalists (Ineos wants to frack in the UK) In 2013, Ineos took on the unions at its loss-making Grangemouth petrochemicals plant, threatening to shut it down before eventually forcing through cuts to pension benefits.

Together with new investment and the import of cheap shale ethane feedstock by its supertanker from the US, this seem to have done the trick - at least from a business perspective. The Grangemouth petrochemicals business made €150m of net profit last year, according to a filing.

Be a patriot, unless it costs too much

Mr Ratcliffe clearly likes the UK or he wouldn’t keep buying assets there, but it’s a testy relationship. He’s justifiably criticised its government for allowing the industrial base to wither and has a soft spot for German engineering - he’s developing the Defender there and prefers Germany’s more consensual labour relations.

It’s harder to justify his attitude toward tax. In 2010, he uprooted key staff and decamped to a village near Geneva when the Labour prime minister Gordon Brown wouldn’t let Ineos defer a big sales-tax bill. Mr Ratcliffe returned to the UK in 2016, but is now poised to disappear to Monaco, which also has a pretty favourable tax system.

This also makes you wonder about his support for Brexit. He’s not the only wealthy Brexiter who’s explored routes out of Britain for their own money or assets - an option not open to most Brits if the economy tanks. But Britain’s departure from the EU may yet prove harmful to Mr Ratcliffe’s own financial interests, too, including his nascent car business. Ineos’ annual report isn’t exactly a glowing endorsement of Brexit, warning that it could “disrupt the free movement of goods, services, capital and people” and “significantly disrupt trade in the UK and the EU markets in which we operate”.

Given his desire for Britain to quit the EU, it seems only fitting that he still has a dog in this fight too.

Whether he watches it from Monaco or anywhere else.

Bloomberg