Gaurang Mehta, who owns a restaurant on the outskirts of Mumbai, is worried about the future of his business.

Things were just starting to pick up after it was hit hard by nationwide lockdown restrictions in India last year. It therefore came as a huge shock to him and many other business owners when the local government imposed fresh curbs this month amid a record surge in Covid-19 infections. These include only allowing restaurants in the state to offer deliveries.

“I won't be able to pay the rent and I won't be able to pay salaries,” says Mr Mehta. “Our problems will only increase.”

India's financial capital, Mumbai, and the wider state of Maharashtra – by far the worst affected in terms of the latest Covid-19 infections – has introduced some of the strictest curbs. In the state that generates 15 per cent of India's gross domestic product, most citizens can only leave home to work in essential services or to carry out necessary tasks. Most establishments, including shopping malls and cinemas, are shut once again until at least May 1.

Several other parts of the country have also introduced new measures to tackle the spread of the virus, with weekend curfews now in place in the nation's capital, New Delhi. India on Saturday recorded a record daily high of 234,692 new coronavirus infections, according to data from the country's health ministry. This brings total Covid-19 infections to date to more than 14.5 million.

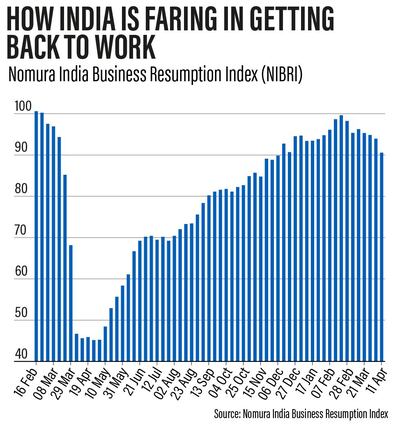

Economists say that the massive second wave of the virus in India poses a threat to the country's economic recovery.

“Numerous restrictions have been imposed by several states to curb the sharp rise in virus cases, which could have an impact on the economic activity and slowdown the recovery anticipated,” says Siddhartha Khemka, the head of retail research at Mumbai-based Motilal Oswal Financial Services.

India only recently emerged from a pandemic-induced recession after the economy shrank by 23.9 per cent at the height of movement restrictions in the April to June quarter last year, followed by a further contraction of 7.5 per cent in the following quarter as restrictions started to ease. The latest official numbers showed that India's GDP returned to growth of 0.4 per cent in the quarter to the end of December. But the impact of the crisis pushed many companies to the brink, with smaller firms and sectors including tourism and aviation hit particularly hard.

In a report published last week, Barclays said the various local Covid-19 curbs being imposed in India could cost the economy $1.25 billion a week and shave 140 basis points off GDP growth for the current quarter.

Meanwhile, ratings agency Moody's Investors Service has warned that the second wave of infections in India poses a credit-negative threat.

It “presents a risk to our growth forecast as the virus management measures will curb economic activity and could dampen market and consumer sentiment”, according to Moody's.

However, the fact that the country has not imposed a blanket nationwide lockdown and the continuation of India's massive vaccination drive could help to mitigate the impact, the agency added. Moody's still forecasts a double-digit expansion of India's economy this year from 2020's low base.

But there is a great deal of uncertainty.

“Both the pandemic situation and its impact on growth continue to evolve,” says Sonal Varma, the chief economist for India at Japanese investment bank Nomura. “The key concern is when lower mobility translates into lower out-turns in other real economic growth indicators.

“We do expect more states to impose restrictions in coming weeks.”

India's central bank, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), also highlighted the threat to economic growth due to the resurgence in infections.

“Fiscal and monetary authorities stand ready to act in a coordinated manner to limit its spillovers to the economy at large and contain its fallout on the ongoing recovery,” said Shaktikanta Das, the governor of the RBI, as he announced that the central bank had decided to keep interest rates on hold during this month's policy meeting because of upside inflationary risks.

The RBI has taken several steps to boost liquidity in the system amid the Covid-19 crisis, including scaling up open market operations and the implementation of two emergency interest rate cuts last year. It has also committed to buying $14bn of government bonds this quarter.

But such measures are fuelling the depreciation of the Indian rupee.

The currency was Asia's strongest performer in the last quarter but it has now become its worst as it weakened past 75 to the US dollar for the first time in eight months last week.

Accelerating inflation “amid rising crude oil and metal prices is a negative trigger for the Indian rupee”, explains Sugandha Sachdeva, vice president of commodity and currency research at Religare Broking. “A sharp surge in the domestic gold imports in March and abundant rupee liquidity after the RBI’s announcement of its bond buying programme are other headwinds for the rupee-dollar exchange rate.”

Ms Sachdeva says that the 75.50 mark may act “as a short-term support .... but the Indian rupee looks broadly skewed on the negative trajectory”.

On the ground, there are widespread concerns among industry leaders about the impact of Covid-19 measures on operations.

Some migrant labourers have already left cities once more for their home villages as they fear being left stranded without work.

“The real estate and construction industry is witnessing project delivery challenges due to the reverse migration of migrant workers and the pending supply of orders for construction material,” says Vinit Dungarwal, director at AMS Project Consultants, a construction consultancy based in Pune in Maharashtra, who explains that the sector was just about adapting to “the new normal” when the second wave struck.

“Covid-19 has disrupted the supply chain and consumer behaviour,” he adds.

Aditya Kushwaha, the chief executive at property developer Axis Ecorp, says that the resurgence in infections is a challenge for the real estate sector, which had managed to stage “a great rebound” following last year's lockdown.

“The second wave of coronavirus is a cause of concern and buyers and investors too are taking a cautious approach at the moment,” says Mr Kushwaha.

It is a relief to him and other developers, however, that authorities are allowing construction to continue amid the current curbs, with strict procedures to be followed such as keeping labourers on site.

The company is also taking its own steps to try to ensure that work continues.

“We're encouraging our labourers to stay back by offering them food storage, provisioning medical supplies and additional daily wages,” says Mr Kushwaha.

Although the outlook remains clouded for now, some economists remain optimistic that India is well positioned to quickly resurface from its latest struggles with the pandemic.

“Overall, we expect a loss of sequential momentum in the second quarter of 2021, even though we expect the medium-term growth upcycle to remain intact due to ongoing vaccinations, the lagged impact of easy financial conditions, front-loaded fiscal activism and strong global growth,” says Ms Varma.

For now, Nomura is maintaining its recently downgraded projection for the financial year ending in March 2022 of GDP growth at 12.6 per cent, compared to an earlier forecast of 13.5 per cent.

“The impact is nowhere as severe as last April on any of the parameters,” says Ms Varma.

For restaurant owner Mr Mehta, however, the situation for his business continues to worsen as the pandemic rages on. His concern is that his eatery may not survive the latest wave of the virus.

"Our sales have completely fallen. The circumstances aren't getting any better."