Iran may be losing more than just crude oil exports with just over three days left until the US re-imposes sanctions on Tehran’s oil industry.

In mid-2012, as the US imposed sanctions on entities and financial institutions dealing with Iranian oil and payments and Europe embargoed crude imports from Tehran, the impact was devastating.

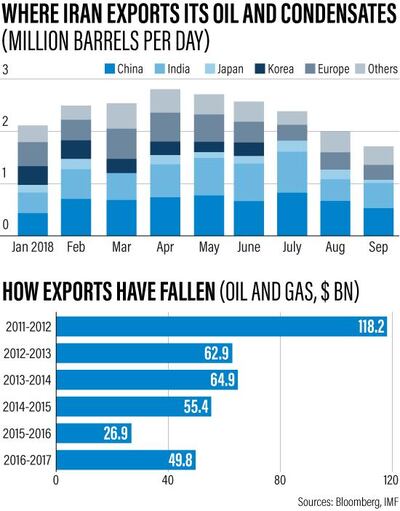

Iranian oil and gas exports which netted the country $118.2 billion (Dh434bn) in the 2011-2012 financial year ending March, plummeted to $62.9bn the following fiscal year, according to International Monetary Fund figures. The erosion in earning power sent the rial plunging against the US dollar and Iranians took to the streets, twisting Tehran’s arm to join the negotiating table over its nuclear programme.

The scene today is not very different and likely to get worse

On May 8, US President Donald Trump pulled out of the nuclear deal struck in 2015 and said he would re-impose US sanctions on Iran, triggering a 180-day countdown to reinstate economic barriers that were lifted in 2016.

Iranian oil exports have plunged 36 per cent to 1.6 million barrels per day at the end of September from 2.5 million bpd at the end of April, translating into nearly 900,000 bpd, according to Bloomberg data.

Experts expect Iran oil exports to plunge to a low of 1 million bpd if the US does not grant waivers to countries that continue to import oil from Tehran. Exports of crude and condensate, a light oil that fetches a higher price than standard oil, plunged in September to their lowest level since February 2016, according to Bloomberg data.

Many countries, mainly India, China and Turkey are in a wait-and-see mode and are discussing getting waivers from the US, which has indicated that it wants Iranian oil exports to go down to zero.

Several countries “may not be able to go all the way to zero” right away on purchases of Iranian oil after US sanctions on the Middle East nation take effect, White House national security adviser John Bolton said on October 31.

“We want to achieve maximum pressure but we don’t want to hurt friends and allies," Mr Bolton said.

_____________

Read more:

Iran to face recession as US sanctions bite

Iranian inflation set to rise sharply as US sanctions deadline approaches

_____________

Whether waivers are granted or not, sanctions will exacerbate an already weak banking infrastructure that had forced many Iranian lenders to offer unsustainably high levels of interest rates of 30 per cent to depositors in the pre-2015 sanctions regime.

Iran needs hard currency to pay for its imports and the less oil it sells the fewer dollars it has to pay for goods and services.

The IMF had forecast in March Iran’s gross official reserves to reach $111.7bn this 2017-2018 financial year, which equates to 14.6 months of imports. Reserves are expected to have fallen further as the rial has lost as much as 75 per cent of its value since the beginning of the year, stoking inflation.

As panic set in, amid the run up to sanctions and a plummeting national currency, Iranians sought refuge in gold bars and coins as a haven for their investments. Demand for gold reached 21.1 tonnes in the third quarter of this year, the highest level since the second quarter of 2013, accounting for three-quarters of demand in the Middle East, according to the World Gold Council.

“As hard currency inflows decline, the rial will remain subject to downside pressure,” said Andrine Skjelland, Mena analyst at Fitch Solutions, part of the Fitch Group. “Inflation, which is also fuelled by rapid money supply growth, in turn looks set accelerate. This will weigh on domestic investment and consumption.”

Fitch estimates inflation in Iran to average 33.2 per cent in the 2018-2019 financial year, nearly double its previous forecast of 17 per cent. Last year it stood at 9.6 per cent. With the deteriorating financials and in the wake of criticism from hardliners at home, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani has had to replace the central bank governor while policymakers ousted his economy and labour ministers over the summer.

"We view it as unlikely that the Iranian authorities will have the capacity to fully meet import demand over a sustained period of time under tightening US sanctions," said Ms Skjelland. "We therefore believe it is likely that the authorities will eventually devalue the preferential exchange rate or narrow the definition of basic goods that qualify for imports at that rate."

Inflation will reach 35 per cent this year and 40 per cent in 2019 as sanctions bite, according to the Institute of International Finance. Imports are projected to fall 10 per cent in volume terms in 2018 from a year earlier.

“Iran will rely on a combination of barter trade and other foreign currency payment to buy goods from foreign countries,” said Garbis Iradian, chief Mena economist at the IIF.

If Tehran goes down the barter deal route, it won’t be the first time.

During the sanctions regime under then US President Barack Obama, Iran engaged in barter deals and used local currencies such as the rupee to sell oil to India, Tehran’s second-largest oil customer after China.

India imported over 488,000 bpd of oil from Iran in September, down from 655,000 bpd in April, Bloomberg data show.

“In China it is pretty easy [to do barter deals] because they sell everything. The question is how much China wants to go around the sanctions and set up these payment systems,” said Roger Diwan, vice president of financial services at IHS Markit. “With India you have less options with what you can do with it [a barter deal].”

The European Union, Tehran's third-largest oil customer, has also cut its exposure to Iranian oil, although it is still party to the nuclear deal struck in 2015.

The EU is planning to set up a special payments vehicle to allow its companies to buy oil from Iran and bypass US sanctions. But companies are reluctant to engage with Tehran nonetheless.

"If you are an entity that has any kind of commercial relationship with the United States and exposure to the US financial system there is a risk of violating sanctions," said Neil Davidson, head of the oil industry and markets division at the Paris-based energy watchdog, the International Energy Agency.

“It is that risk which has led many major companies such as [France's] Total to pull out of deals with Iran even though the European Union has announced a scheme to protect European companies from exposure to the US.”

Energy major Total pulled out of a $4.8bn deal to develop gas reserves in Iran, which is in dire need of foreign technology to prop up its dilapidated oil and gas industry.

Not everyone sees an end in sight for the sanctions era.

"This US administration would like to see the imports go to zero but I don’t think India and China can afford to not buy Iranian crude," said Peter Kiernan, lead energy analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit. "The Obama administration had a purpose with the sanctions and that was to bring about negotiations to the nuclear issue and the intent of sanctions was to force other countries to reduce the purchase of Iranian oil. But this time around what is the endgame? It is going to be indefinite."

A further issue that Iran faced in the past is shipping because international insurers refused to deal with Tehran and its maritime transport last time around for fear of falling foul with the US.

“Another limitation is insurance and shipping but Iran has a fairly large fleet of tankers to continue to export 1 million to 1.3 million bpd of crude,” said Mr Diwan.

What do the sanctions mean?

With the US sanctions against the Islamic Republic set to take effect on November 4, we take a look at what it encompasses, what’s at stake, and who is likely to be most impacted.

What are the US sanctions against Iran?

The US announced targeted sanctions against the Islamic Republic in May 2018, after pulling out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, a deal brokered by the Obama administration, which allowed Tehran to earn revenues from the sale of oil and condensates and okayed its slow integration back into global financial markets. The latest sanctions being pushed by the US administration under President Donald Trump imposed 90 and 180-day ultimatums for countries to wind down all their trade engagements with Iran.

What happens on November 4?

While the 90-day period ended on August 6, the 180-day period ends on November 4, the deadline which the Trump administration has given to Tehran’s oil importers to completely halt their supply of Iranian crude. The measures are the harshest sanctions against Iran’s energy industry, which has been crippled by lack of infrastructure development due to the earlier wave of sanctions, which came into effect in 2012.

Why does the loss of Iranian crude matter?

Iran, a founding member of Opec is the third-largest producer of oil in the Middle East after Saudi Arabia and Iraq. The country has some of the oldest refineries dating back around a 100 years and a decades-long rapport with buyers in Asia. A halt in the supply of Iranian crude will remove around 1.1 million barrels per day of oil off the market, at a time of already limited spare capacity among Opec producers.

What will be the impact on the oil markets?

Analysts have cautioned that the loss of Iranian barrels could spike oil prices, which have already breached the $80 per barrel mark after three years, close to $100 levels by year-end.

Who are Iran’s biggest buyers of crude?

China is the biggest buyer of Iranian crude, followed by India, South Korea, Turkey, Italy and Japan. Iran’s major buyers have already cut back on crude supplies to a 32-month low with the South Koreans and Japanese halting supply completely.

What will be the impact on the top buyers?

Analysis by firms such as Wood Mackenzie suggests that Chinese imports will average 500,000 bpd, while India and Turkey will continue to buy on a reduced basis, with New Delhi continuing to export around 150,000 bpd. Countries such as Syria, where Iran is involved in a proxy war, will likely continue imports of around 50,000 bpd on a cargo-by-cargo basis.

Can they seek exemptions?

The European Union has been trying to persuade the US to exempt SWIFT from the latest sanctions and has also worked to shield its companies that work in Iran.

What are the penalties if they don’t gain exemptions?

If companies continue to buy and trade in Iranian oil without procurement of waivers, they will not be able to access the US financial system. Iran and China have both started looking at alternative payment options to the US dollar for oil sales such as the Yuan exchange and cryptocurrencies to find a way to bypass the US financial system.

Jennifer Gnana