President Donald Trump often cites China’s massive exports to the US as a grave injustice hanging over the world economy. But lately it pays to look at Chinese imports for the pain that his tariff wars are inflicting on global growth.

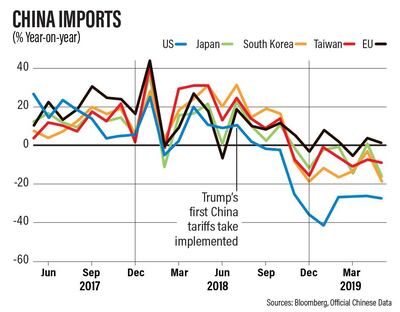

The world’s biggest trading nation last month saw imports from Japan, South Korea and the US fall sharply from a year earlier, according to official data. The 27 per cent fall from the US is perhaps not surprising given a year of tit-for-tat tariffs, but a drop of 16 per cent from Japan and 18 per cent from South Korea is reason to consider the broader effects of Mr Trump’s trade battles.

Such data illustrate why trade is at the top of the agenda for this week’s G20 meeting of leaders who preside over more than three-quarters of the global economy. While much of the focus will be on Mr Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping’s ability to resume talks, the other leaders in attendance have their own stakes to worry about.

Global commerce is “being hit by new trade restrictions on a historically high level”, World Trade Organisation director general Roberto Azevedo said in a report on Monday that pointed to an increase in protectionist measures by G20 countries. “This will have consequences in increased uncertainty, lower investment and weaker trade growth.”

Almost every day brings fresh data on the economic impact.

An analysis released on Monday by Bloomberg Economics of the more than 10,000 Chinese product categories hit by tariffs already found they had led to a 26 per cent fall in the value of their exports to the US in the first quarter of 2019.

That was before the recent breakdown of US-China talks and an increase on May 10 to 25 per cent from 10 per cent of tariffs on products worth some $200 billion (Dh734.5bn) in annual trade before the conflict, the largest tranche of $250bn in imports affected. Mr Trump has also threatened to hit a further $300bn in imports from China.

Monthly trade data are volatile. But in numbers like China’s May import data, WTO chief economist Robert Koopman sees evidence of the Trump trade wars rippling through supply chains and dragging on the world economy.

Big economies such as the European Union, China and the US are slowing for reasons ranging from Brexit to faltering manufacturing in China to the disappearing fiscal stimulus from tax cuts in the US.

Adding to the malaise is rising uncertainty over the direction of the global economy and trade that is dampening investment, Mr Koopman says. Then there is the direct cost of tariffs and counter-tariffs for businesses. Each feeds into the other and a global economy changing in response, he says.

Mr Trump and his aides insist his push to take on China and go beyond that by threatening allies such as the EU and Japan with auto tariffs among other things is aimed at rebalancing America’s economic relationships.

Those actions have nothing to do with the slowdown under way in the world economy, they argue, though institutions such as the International Monetary Fund have called escalating trade tensions the largest risk out there.

“I don’t believe for a second that what we’re doing is having a largely negative effect on economic growth,” Robert Lighthizer, Mr Trump’s chief trade negotiator, told a congressional committee this month, pointing to a US economy growing faster than G7 peers. “The economy in a lot of other countries is slowing down and it doesn’t have anything to do, in my judgment, with what we’re doing.”

Robin Brooks, chief economist at the Institute of International Finance, says it is too early in the trade wars to blame them for any broad economic trends. Nations such as Germany, which has been hit by Brexit and a slowdown in Turkey, have faced idiosyncratic forces, he argues. Data like those showing a slowdown in exports from Japan or South Korea to China represent “just the normal ups and downs of global manufacturing.’’

While economists such as Mr Koopman say it is hard to say how much Trump’s actions are to blame for a slowdown there’s no doubt they are changing trade flows. Put another way: Mr Trump is causing globalisation to adapt rather than go into reverse as he intended.

Production is shifting to other countries rather than coming home. Bloomberg’s new analysis found that in the first quarter of 2019, Taiwan saw sales to the US of products hit by Mr Trump’s China tariffs rise about 30 per cent from a year earlier, while South Korea’s jumped 17 per cent. Vietnam saw sales of China-tariffed products to the US increase 27 per cent.

“Globalisation going into reverse would mean a lot of the production coming back to the domestic market,’’ Mr Koopman says. “That’s not what we are seeing.’’

China also hasn’t let Mr Trump’s penalties go unanswered. Peterson Institute analysts point out that even as it has retaliated and raised import taxes on US products, China has lowered duties on goods from the rest of the world. Still, China’s data last month showed it’s not clear that strategy has resulted in a broad surge in non-US trade just yet.

So whatever the outcome of the Trump-Xi talks at G20 later this week, the early disruptions may leave lasting scars. “Even if we get some agreement at the G-20 meeting, we may underestimate the damage already done to capex planning and corporate sentiment by the trade war,” Torsten Slok, Deutsche Bank’s chief economist, said on Sunday.