Logistics provider Blowhorn has managed to double its business to achieve 2 million deliveries a month, servicing more than 70 cities in India amid a surge in online purchases since the pandemic hit last year and as the logistics sector continues its own process of going digital.

The technology-driven, Bangalore-based company connects customers to warehousing space and trucks for deliveries within cities via its website and mobile app.

Mithun Srivatsa, who co-founded Blowhorn in 2014, describes his company as “an Uber for trucking or moving goods” and “an Airbnb for warehousing”, as it owns neither the trucks or warehouses available through its network. The company has received investment from the Michael and Susan Dell Foundation and India's Venture Catalysts, among others

“E-commerce adoption took off during the pandemic and has spurred more and more people online,” says Mr Srivatsa, who is the company's chief executive. “Suddenly you had people like my mother, who was 65, deciding to buy their groceries online.”

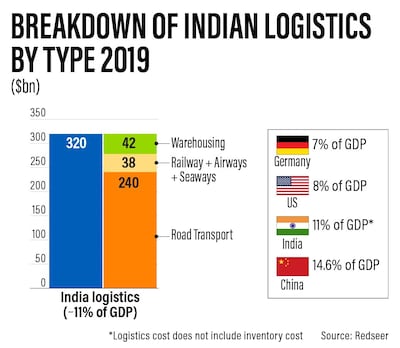

India's logistics sector was worth $320 billion in 2019 and accounts for 11 per cent of the country's GDP, according to a report by consultancy Redseer.

“Logistics have remained a backbone for many industries and over the years has enhanced its technology-based offerings to suit various sectors and their needs,” the consultancy says.

Its data shows that e-commerce transportation grew 70 per cent year-on-year to 2.55 billion shipments in 2020, and it projects that this will increase to about 10.5bn by 2025.

“The industry overall right now is very bullish,” says Anjani Mandal, the chief executive at Fortigo Network Logistics, a trucking platform based in India's tech hub, Bangalore. “The e-tailers have had a rapid growth because of the lockdown.”

In March last year, India introduced one of the world's strictest nationwide lockdowns in response to the pandemic, which meant that people could only go out for essential goods or services. For the first month of the lockdown, Mr Srivatsa at Blowhorn explains that the company did “a small fraction of volumes we were doing before” because of the “chaos” and “mass confusion” that the restrictions caused.

But as people moved towards online orders, the service started to see a surge in demand from its e-commerce clients and did “some of our best growth months during the pandemic”. With this boost, the company is expecting to achieve profitability this year.

The logistics market is made up of of road transport, warehousing and other delivery networks such as air, sea and railways.

Road logistics, at a value of $240bn in 2019, makes up the lion's share at 75 per cent of the market, according to RedSeer. It says that “the road logistics market and last mile delivery is moving in the right direction to profitability”.

The last mile delivery segment, which is the area Blowhorn focuses on, is expected to expand to become a $6bn to $7bn market by 2024, up from $800m to $900m in 2019, Redseer estimates.

There have been several factors working in the sector's favour.

“In recent years, there has been a rise in e-commerce with more fleet in place to cater to the increasing demand,” says Nakul Singh, the co-founder at ANS Commerce, an e-commerce enabler that helps brands to sell online.

This has prompted “growth in the investment in infrastructure, last-mile connectivity, and emerging technologies are streamlining the logistics landscape in India”, he says.

The warehousing sector in India, which makes up about 13 per cent of the logistics industry, is going from strength to strength because of the e-commerce boom.

“The Covid-19 pandemic has been positive for growth in the warehousing sector,” says Niranjan Hiranandani, the co-founder and managing director of Hiranandani Group, a Mumbai-based property developer. “A huge quantum of Grade A warehousing spaces are being created.”

The founder of digital logistics platform, Zipaworld, believes that better integration of parts of the network can create more efficiency.

“The increasing logistics and supply chain cost, which is almost 14.5 per cent [of the cost of goods] in India shouts out for integration and digitalisation of processes,” says Ambrish Kumar, who set up the company last year in the midst of the pandemic.

“The age-old traditional logistics sector is yet to fully adapt to technological advancement”, with the e-commerce sector demanding transparent tracking of shipments and accurate delivery timeframes, he says.

Amitava Saha, the founder and chief executive at XpressBees, an express logistics provider in India, says that its use of technology has been a major factor in its strong performance during the pandemic, as it has given it “an ability to re-route [and] to avoid hotspots”.

Yet although technology is proving to be a boon, there are barriers to its adoption.

“There's a lack of trained manpower,” says Mr Saha. “As logistics is becoming more tech-enabled, you need a certain standard of people to operate or grow the company, which is very different to the manpower that most traditional logistics companies had.”

Mr Mandal at Fortigo, which connects clients and truck fleet owners in the broader road logistics sector, explains that despite the overall bullishness, a lot of truck owners have been hit hard by the pandemic. This was because deliveries across states and between cities became more challenging due to Covid-19 curbs, and truck owners struggled to pay off loans on their vehicles once the Reserve Bank of India's six-month moratorium on loans ended in October.

“As a consequence, the number of trucks started to decline at the end of 2020 and by February 2021, the population of trucks went down by 20 per cent, from 5 million to just under 4 million,” he says.

In the short term, business is taking a hit during the current massive second wave of Covid-19 infections, as many factories remain shut.

This has hit Fortigo's business, as the company relies on the movement of metals and materials, as well as fast-moving consumer goods. There have been other challenges posed by the second wave for logistics firms in India, including staff coming down with the virus and workers fleeing to their home towns, creating labour shortages.

On Saturday, 120,529 new cases of Covid-19 were discovered and the country recorded 3,380 new deaths, according to the Ministry of Health. This brought the total number of cases since the pandemic began to almost 28.7 million and the number of deaths to 344,082.

In the long run, though, the industry remains bullish on the transformational power of technology.

Road logistics in India is highly unorganised, with most trucks owned by individuals or small businesses. Technology has started to bring more structure to the industry, Mr Mandal says.

“The main development that happened in the industry was the role of digital logistics became dominant in the very large organisations,” he says. This has led to rapid expansion for companies like his in recent years.

Digitalisation is still relatively new, and there is a long journey ahead, but the sector will have no option but to adapt, XpressBees' Mr Saha says.

“I believe that going ahead, tech-based logistics will grow at a much faster pace and take over a bigger share of the market pie compared to traditional logistics companies.”

Mr Srivatsa also expects substantial growth as “a 100 year old industry” goes through a period of disruption.