Emerging markets are rounding off the year with few excuses to keep floundering into 2019.

After a turbulent year that threatened to turn into a rout as US monetary conditions tightened and the trade war erupted, markets are finally showing some strength - in part because valuations have fallen so low.

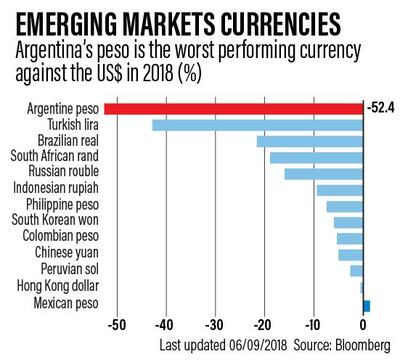

While the currencies, stocks and local-currency bonds of developing economies are all heading for their worst year since 2015, they have rebounded from lows in the past few months. Emerging-market stocks slid deeper into a bear market in October as rising Fed rates pushed up the value of the dollar and a trade war intensified, hitting countries such as Indonesia and South Africa that had weaker fundamentals, Bloomberg said. Argentina and Turkey added homegrown problems to the mix, fuelling contagion risks, while Mexico and Brazil navigated through presidential elections.

“Emerging-market risk premium has risen dramatically this year in many cases, laying the groundwork for potentially a much better outcome in 2019 with the caveat being the external environment can’t get worse,” said Michael Kushma, chief investment officer for global fixed income at Morgan Stanley Investment Management in New York. “EM performance this year has been disappointing, but disappointing for reasonable reasons.”

Here are some highs and lows of 2018 across global emerging markets:

China-US trade war

China offered a series of headlines that moved markets. Many revolved around trade friction with the US and the imposition of tariffs on imports by both countries. The leaders of the two nations met on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Argentina on December 1 and agreed to temporarily halt the imposition of new tariffs.

China’s policymakers have tried to encourage lending to cash-strapped private companies as the economy slows and the trade conflict with the US rolls on. The central bank has also cut the reserve-requirement ratio four times this year.

Historic meetings between North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and Trump as well as South Korean President Moon Jae-in have averted the risk of war, reducing what is often called the "Korea discount".

However, the effects of receding geopolitical risks were offset by the US-China trade war and have done little to boost South Korean assets overall. The Kospi index of shares entered a bear market along with China and the Philippines.

Investors will be keeping an eye on Chinese economic data for signs of impact from the trade war. Retail sales, fixed-asset investment and industrial production will be released on Friday.

Indonesia's aggressive Hiking

The rupiah’s slump to levels not seen since the Asian financial crisis in 1997-1998 triggered an unprecedented policy response both from the central bank and the government. The interest rate was raised six times this year to 6 per cent to shield the currency that was swept up in the emerging-market rout. The government swung into action, placing curbs on imports, pushing import substitution and halting projects worth billions of dollars to cool demand for dollars.

With the presidential elections due in April, investors are keenly watching if the government gets more populist or sticks to fiscal discipline to rein in the twin deficits, seen as the weak spot for Southeast Asia’s largest economy.

Erdogan fights

Investors fled amid a triple-whammy from sanctions related to the detention of a US pastor, the central bank’s reluctance to tighten policy and broader outflows from emerging markets. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s conviction that higher interest rates cause inflation didn’t help to restore investor trust, either. While the central bank eventually underpinned the lira by raising borrowing costs, it was left with plenty of bruises, with the currency heading for its worst year in over a decade.

Turkish economic growth dwindled to 1.6 per cent year-on-year in the third quarter, official data showed on Monday, falling short of forecasts as a lira crisis and soaring inflation took its toll on the economy.

The major emerging market economy grew more than 7 per cent last year but a slowdown to just over 5 per cent in the second quarter has accelerated in the second half as a slide in the lira currency begins to bite.

In a Reuters poll, economists had forecast third quarter growth of 2 per cent year-on-year. The lira eased to 5.3047 against the dollar after the data from 5.2950 beforehand.

Third-quarter GDP shrank a seasonally and calendar-adjusted 1.1 per cent from the previous quarter, data from the Turkish Statistical Institute showed.

Revised data showed the economy had expanded 5.3 per cent year-on-year in the second quarter, from a previously reported 5.2 per cent.

The lira has slumped 28 per cent against the dollar this year, but has rebounded from record lows in August when it was as much as 47 per cent weaker against the US currency.

The lira crisis sent annual inflation to more than 25 per cent in October, its highest rate in 15 years, before easing in November.

Russia faces sanctions

Geopolitics have weighed on what otherwise might have been a brighter year for the rouble. Sanctions related to Russia’s alleged meddling in 2016 elections, the risk of restrictions targeting rouble bonds, jitters over the poisoning of a former spy in the UK and US mid-term elections sent the currency on its third straight year of declines. That’s despite higher oil prices, what may be the first budget surplus since 2011 and one of the highest real interest rates in the developing world.

While the majority of economists expect Russian policy makers to keep their benchmark rate at 7.5 per cent, Barclays Capital predicted that accelerating inflation, sanctions risks and a less-favourable environment in emerging markets will prompt the central bank to hike on Friday and once more in the first quarter.

Philippine pause

The Philippine central bank could pause its tightening cycle on Thursday after inflation in November eased from a nine-year high. Given that monetary policy is firmly tied to inflation outlook, Nomura sees the overnight borrowing rate at 4.75 per cent for at least a year, Euben Paracuelles, an economist wrote in a note

The peso is the best-performing emerging-market currency in the second half of 2018.

Ramaphoria fades

Investor euphoria over a new leader pledging to fight graft proved to be short-lived for the rand as the South African government stoked concerns with a move to expropriate land without compensation, and a return to recession increased the risk of a third junk credit rating. Delays in President Cyril Ramaphosa’s reform agenda and the ousting of his Finance Minister shortly before the annual budget presentation added to global headwinds.

Populists arise in Latin America

Latin America’s two biggest economies, Brazil and Mexico, elected populists in 2018 from opposing ends of the political spectrum, driving assets in opposite directions. While investors warmed to Brazil’s President-elect Jair Bolsonaro as he handed off fiscal responsibilities to former fund manager Paulo Guedes, they got spooked by Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador in Mexico after he cancelled a $13 billion airport project. While Brazil’s benchmark stock index has soared to record highs, Mexico’s index has fallen 10 percent since the presidential vote on July 1.

Argentina was the Latin American country without any political drama though that saw the biggest declines in the region and worldwide. As US interest rates rose, Argentina’s widening fiscal and current account deficits triggered a stampede out of the country’s assets that sent the peso down 50 per cent against the dollar this year as of December 7.

It took drastic action from the government and the central bank to bring the situation under control. First, the state turned to the International Monetary Fund for a $56.3 billion loan. Then the central bank froze the money supply, soaking up liquidity in the market and pushing interest rates above 60 per cent. The medicine worked, but at the cost of a second recession in three years.

Consumer price data due for release in Argentina on Thursday are expected to show inflation is decelerating. That would be a welcome break after the central bank hiked interest rates to world-beating levels to prop up the faltering peso.

The world’s riskiest bond market lived up to the hype in 2018 when Venezuela defaulted on $7bn in debt payments. In May, President Nicolas Maduro survived reelection in a vote widely seen as a charade, deflating investor optimism that a new administration could pave the way for a creditor-friendly restructuring. While the government blames the US and other “imperialist forces” for its financial woes, state-run oil company Petroleos de Venezuela has selectively forked over funds to pay one bond that’s backed by shares of its US refiner Citgo.