The Iranian-American artist Shirin Neshat’s dark kohl-lined eyes are immediately recognisable. Now, she is bringing their gaze on Iranian and Arab women’s resistance to oppression all the way to Washington, this most political of cities.

The Hirshhorn Museum’s retrospective in Washington, just steps from Congress, coincides with a diplomatic push to seal a nuclear deal with Iran, which has revived interest in relations between Tehran and the West.

The non-linear narrative of the exhibit provides a glimpse not just at Neshat’s art and life, but also the trajectory of Iran in modern times, from the 1953 coup to the 1979 Islamic Revolution to the recent Green Movement.

“My work is the expression of my feelings and relationship with politics ... the rise of anxiety and the joy of the prospect of peace,” said Neshat.

At 58, the New York-based artist is unassuming and soft-spoken, her diminutive frame contrasting with the boldness of her work. Although the self-described secular Muslim insists that her exile is “self-imposed”, her work is so controversial in Iran that it has yet to be shown there publicly, and she has not returned since 1996.

The female protagonists in her video installations are constantly on the move, their lives at risk at every moment.

In Neshat's Turbulent (1998), a singer defies a ban on singing in public.

In Fervor (2000), a woman dares seek the gaze of her beloved, while in Rapture (1999), the women embark on a boat, leaving the men behind, for what could be interpreted as either suicide or freedom.

Each video of the trilogy features split screens dividing men and women, a theme taken up in more mystical fashion in Women Without Men, a five-part video series that was later made into a feature film.

“My perspective on the situation of the Iranian women, particularly of course since the Islamic Revolution, is that the more they are up against the wall, the more resilient, confrontational and rebellious they have become,” Neshat said.

“As our perceptions of the Middle East and Iran have changed, so has her work,” says the Hirshhorn’s new director Melissa Chiu.

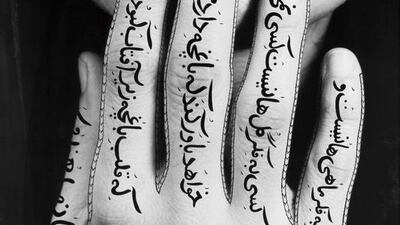

Neshat inscribed calligraphic texts and illustrations from the ancient Persian epic poem Shahnameh for her monumental series of photographic portraits Book of Kings. Unlike her previous work, the Iranian and Arab subjects are youthful and unveiled, reflecting changes after the Green Movement and the Arab Spring uprisings.

The portraits also include poetry by contemporary Iranian writers and prisoners.

Our House is on Fire closes the chapter, with nearly indecipherable calligraphy inscribed in the folds and wrinkles of her elderly subjects' skin.

Only tears, shed for loved ones lost to violence, are left untouched.

The series was inspired by the Egyptian revolution, to which Neshat became an inadvertent witness while working on a film about seminal singer Umm Kulthum, a project due to be shot early next year in Egypt and Morocco.

Neshat, whose mother and siblings still live in Iran, has narrated the heart-wrenching condition of the diaspora from across oceans, having left in 1974 to study abroad.

After the 1979 Islamic Revolution that overthrew the United States-backed Shah, Neshat would not return until 1990. And then, she found a country so profoundly changed that people even behaved and dressed differently.

“The Islamic Revolution is what caused our separation, years and years of separation,” Neshat says.

“If there is a universality in the work that I make, it is a question of tyranny and the people’s power, and the survival and resilience of the human spirit in the face of tyranny and dictatorship.”

The visit was the catalyst for the provocative Women of Allah (1993 to 1997) series of black and white photographs, in which Neshat herself appears veiled and toting a gun sometimes pointed directly at the viewer.

In her deeply personal Soliloquy, the artist, clad in a chador, appears in a western city in one projection and in a Middle Eastern city in a second on the opposite wall. Standing at the threshold between two opposite worlds, she finds no peace in either society.

• Shirin Neshat’s works are at the Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, until September 20. Visit www.hirshhorn.si.edu

* AP