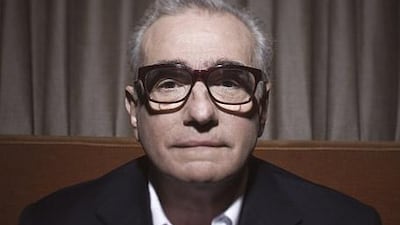

Whether making or discussing them, Martin Scorsese has an insatiable appetite for all things film. On the UAE release of his latest, Shutter Island, the acclaimed director talks to John Hiscock about the past, the future and his partnership with Leonardo DiCaprio. When I told Leonardo DiCaprio I was due to meet Martin Scorsese later that day, he laughed. "Ask him any sort of question and see how he always manages to turn the answer into something related to film," he said. "He's completely and utterly obsessed with cinema." True. Having made four films with him, DiCaprio knows that spending any time with Martin Scorsese is like having the front-row seat at an engrossing lecture by the world's foremost expert on all aspects of films, filmmaking and cinema history.

We were meeting to ostensibly talk about his latest film, Shutter Island, but Scorsese manages to sprinkle his discourse with references to more than a score of other films and a dozen filmmakers, ranging from Alfred Hitchcock to Bertrand Tavernier and including John Ford, Cecil B DeMille and Orson Welles along the way. He talks with infectious enthusiasm about all aspects of filmmaking, from 3D and the use of colour, to camera movement.

DiCaprio swears that the 67-year-old filmmaker often wakes up in the night with an image from some obscure and long-forgotten movie in his head and has to immediately get up and screen the film. Scorsese and DiCaprio are developing the kind of easy partnership Scorsese had with Robert De Niro, with whom he has made eight films. Scorsese credits DiCaprio with giving him what he calls "a new lease on my own creativity" by starring in Gangs Of New York, a film that put Scorsese's then-flagging career back on track.

Then came The Aviator and The Departed and now the two men have teamed up again for Shutter Island, an enigmatic psychological thriller set in the 1950s in which DiCaprio plays Teddy Daniels, a US marshal who is sent to investigate the disappearance of a murderess from an asylum for the criminally insane on a remote island. He finds himself trapped by a violent storm in a world imbued with paranoia about communism and brainwashing, where everything is not as it seems.

At first the usually garrulous Scorsese is finding it difficult to talk much about it without giving away its secrets, although it doesn't take long for him to abandon caution and get into his vocal stride. "When I read the script, I realised it had its roots in something that is classic, that speaks to something that's very basic about our human nature and about who we are, what we want to conceal and what we have to accept," he says. "If we try and know ourselves, are we too afraid sometimes to go to areas that are unpleasant and irrational? Ultimately, what this is all about is 'know thyself'.

"There are references to film noir, references to Psycho, to psychological thrillers, to horror films and to films that are basically composed of dreams, so I think ultimately that even if the surprise ending is known - although it has several endings in a way - hopefully it's a picture that you could watch repeatedly because of the behaviour of the characters." He drew, he says, on film classics such as Cat People, Isle Of The Dead and Out Of The Past with homage to Oracle At Delphi, Rosemary's Baby and I Walk With the Zombie thrown in.

"I've always been fascinated by mysteries of the mind because it's how we perceive what we term reality," he says. "Witnesses in a court of law will swear they saw something but if they had stood two or three feet in another direction maybe they'd have seen it differently." Neat and dapper, dressed in a dark suit, striped shirt and dark tie, Scorsese talks in a rat-a-tat fashion almost without pause, perched on the edge of a chair in a Manhattan hotel suite. He had walked the short distance from his production office where he is working on a documentary about the late Beatle, George Harrison, editing the pilot episode of a gangster TV series called Boardwalk Empire and developing several other projects, at least two of which will again star DiCaprio.

He is unstinting in his praise of the actor, whom, he says, has "remarkable emotional and psychological depths", although they frequently butt heads on the set. "I keep pushing him and keep asking, to the point sometimes where he'll look at me and say, 'You know, I don't know what I'm doing any more.' I say, 'Fine, let's do it again.' And I realise then that all his defences are down and something real is going to happen. I mean something internally, emotionally and psychologically truthful. He's remarkable; he's young and he really seems to have a range that's going to get deeper and stronger."

Scorsese is a director who has always found his best characters outside the mainstream. His films follow psychopaths, loners, losers and mobsters, possibly because he has always considered himself to be something of an outsider. He grew up a sickly child, confined by asthma to his parents' tenement home in New York's Garment District while other kids his age played on the cobblestone streets. "I couldn't run around, I couldn't do anything, so my parents would always take me to the movies and park me there," he recalls. "They didn't know what else to do with me and I loved it."

It was there that he first saw the films that made such an impression on him and forged his career: James Cagney in Public Enemy and White Heat; Orson Welles in Citizen Kane, Jean Renoir's Rules Of The Game and many others, long forgotten by most people but remembered vividly by Scorsese. When he was eight he began sketching shot-by-shot retellings of the movies he had seen and by the time he was 12, the sketches had become originals, often titled "Directed and Produced by Martin Scorsese".

While at New York University, he made three short films, one of which won a Producers' Guild award. He still vividly remembers that first trip to Hollywood 45 years ago. At the awards dinner he met Cary Grant, who asked him his name and when he told him, the famous actor said: "You may have to change that." He made his feature-length directing debut in 1967 with Who's That Knocking At My Door, which was a semi-autobiographical look at an Italian-American Catholic, played by a baby-faced Harvey Keitel, who deals with women as either virgins or whores.

After a spell teaching at the university, Scorsese did what thousands of other movie hopefuls do and headed for Hollywood, where he landed a work-for-hire job with B movie king Roger Corman, directing the Depression-era crime thriller Boxcar Bertha. He then delved into his own experiences to make what would become his breakthrough film, Mean Streets, a gritty semi-autobiographical tale that marked the first of his eight collaborations with Robert De Niro. Although filmed in Los Angeles, Mean Streets brilliantly conveyed the teeming violence and despair of New York's Lower East Side.

For the next decade he toiled in Hollywood, attempting, he says, to imitate the versatility of the old directors. His Taxi Driver earned four Oscar nominations, including one for Best Picture, though none was successful. His next film, the musical New York, New York was a flop. His documentary The Last Waltz was another success, and he followed that with what many consider his masterpiece, 1980's Raging Bull, a searing look in black and white at the former middleweight boxer Jake LaMotta. De Niro won a Best Actor Oscar but Scorsese was passed over for Best Picture and Best Director. He said later: "That's when I realised what my place in the system would be: on the outside looking in."

After 1983's moderately successful The King Of Comedy, he left Hollywood because, he says, he realised he was in an alien world in which he did not fit. He recalled that he would be at a party and someone would ask, "What are you doing here?" Back in New York, he made The Color Of Money, which earned Paul Newman an Oscar and then struggled to make his dream project, The Last Temptation Of Christ, but Paramount withdrew its funding at the last minute due to a ballooning budget and outrage from some Christian groups. An intensely personal project for Scorsese, he forged ahead regardless and the film was finally made, although it continued to generate controversy, which led to some cinema chains refusing to show it.

He hit his stride with GoodFellas, Cape Fear and Casino, but the subsequent failures of Kundun, Bringing Out The Dead and the documentary My Voyages To Italy caused problems when he attempted to raise financing for Gangs Of New York, a project he had worked on for several years. It was only when Leonardo DiCaprio agreed to join the cast that the film received the go-ahead from Miramax. Even so, Scorsese frequently clashed with Miramax boss Harvey Weinstein over the budget and the film's content, but when it was eventually released in 2002, it earned him his fourth Best Director Oscar nomination, though he was again unsuccessful.

It was DiCaprio who again came to his rescue with the next project, The Aviator, a lavish film biography of the bizarre billionaire Howard Hughes, which the actor had worked on with screenwriter John Logan and which Michael Mann was due to direct. But when Mann dropped out, DiCaprio took the script to Scorsese, who gave free rein to his love of old films and the glory days of Hollywood and recreated the era lavishly - and expensively - on the screen. It led the Oscar race with 11 nominations, including Best Picture and Best Director.

He was overlooked for a fifth time, but finally won the Best Director Oscar for his slick 2006 crime thriller The Departed - also voted Best Picture - an honour made that much sweeter when he received a standing ovation and was handed the award by his longtime friends and peers, Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas. Long a champion of film preservation and an outspoken foe of the colourisation of classic black and white movies, he formed the World Cinema Foundation three years ago, an organisation dedicated to preserving and restoring damged films.

Despite the accolades and respect that have finally come his way (he won the Golden Globe's Cecil B DeMille award this year, which was presented to him by DiCaprio and DeNiro), Scorsese still occasionally has problems with the studios, though he is wary about being too outspoken. It clearly rankles that Paramount, after announcing it would release Shutter Island in October last year, then delayed it until this year. The reason given was that the studio did not have the budget to market and promote it last year.

"When it comes to finances, I'm not a studio head and I don't understand it," says Scorsese. "I know they have to spend a great deal of money to release a film, particularly if a lot of money was spent on its budget. It's their product so I have to go along with however they want to support it and promote it, although it was disappointing because we were rushing so hard to finishing it in time. "It's like you're running a marathon and there's a guy near the end who suddenly stops you. But this is the nature of what it is. I don't quite understand it but I think maybe they made a wise decision ultimately."

Although a deeply knowledgeable film historian, he is not so sure about which direction the medium will take in the future. "My sense is that the experience of viewing films is obviously changing, not just because of an iPod or an iPhone or computers, but I think the availability now of so much cinema and the ability to pull it in on different formats is going to be something, maybe not for my generation, but for my daughter's generation," he says. "Maybe they perceive storytelling in a totally different way than we did, which was more classical. Because of the computer, YouTube and because of digitising, things are seen in bits and pieces. My little daughter and her friends are making movies now. "

In a life devoted to film, he has managed to find time to have five wives, three children and several high-profile girlfriends, including Liza Minnelli and actress Ileana Douglas, who appeared in four of his films. It is too early to say whether his 10-year-old daughter Francesca, by current wife, book editor Helen Morris, will follow in his footsteps, but he says: "She and her friends are writing scripts and filming them, though I'm not sure exactly what they are. I've seen one or two but they have to get into the editing of them. I don't say they're going to be filmmakers, but it's a way of expression for them. It's what young people are doing and it's the way it is now."

He veers into a reflection on 3D, which he was fascinated by when he saw it as a child in the early 1950s, before it went out of style. "Now it's back and the newer generation may know how to use it in the same way we use two dimensions. But if you use 3D, you have to write it in the script. Maybe I don't think in those terms. Maybe I only see the camera move left to write, up and down, back and forth and maybe it'll be a real problem for me to go into 3D, but I think it's something that's just a natural progression.

"There's a danger more money will be lavished on bigger spectacles and less spent on more modest films. I'd like to see more support for the more modest films but this is a time of great change. We've entered a new phase and it's going to be exciting. It's a different world." It is a world he intends to be part of. "I am literally obsessed with the filmmaking process and so, given the right circumstances and the chance to learn and experience - whether it's a storm scene in Cape Fear or whether it's the world of aviation and old Hollywood in The Aviator - I find myself wanting to get back on the set and especially into the editing room, to see those images come together."

He thinks for a moment, then with classic understatement adds: "I really enjoy doing it."

Shutter Island is on release in cinemas nationwide.

With apologies for passing over The King Of Comedy, The Aviator, The Last Waltz and many others in a glittering body of 43 films, M nominates Martin Scorsese's five best movies. The order? It doesn't matter - they are all classics. If we were pushed, though, we might opt for Taxi Driver at the top of the pile.

This was the film that introduced the troika of Robert De Niro, Harvey Keitel and Scorsese himself to a big audience and started a rich artistic partnership. Charlie (Keitel) feels a brotherly responsibility for his immature friend Johnny Boy (De Niro) and this hinders his progress up the ranks of the local mob, for whom he acts as debt collector. Scorsese's film is part autobiographical. It is set in the Little Italy area of New York City near the Garment District where he grew up, and Charlie's battles with his Catholic faith and his Mafia ambitions reflect the director's own struggles; before entering New York University Film School he had wanted to train as a priest. Charlie works for his uncle Giovanni and is having a hidden affair with Johnny Boy's cousin, Teresa, who is ostracised, especially by Charlie's uncle, because of her epilepsy. Themes of guilt and self-sacrifice, destruction and redemption, and conflicting loyalties were to become a constant in Scorsese's films. The film was also significant for championing small independent films, showing budding filmmakers they could show their art alongside major productions on the big screen for relatively little money.

Scorsese again teamed with Robert De Niro and Harvey Keitel for this tale about a man's struggle with his demons to find a place in a world from which he feels alienated. De Niro plays unhinged former marine Travis Bickle. Spurned by Cybill Shepherd's presidential campaign volunteer after taking her on a date to a porn movie, he turns mohawked vigilante to rid the streets of the "scum" he encounters in his cab. Memorable scenes include De Niro's oft-quoted "You lookin' at me" conversation into the mirror and the gory climax in which Bickle shoots pimp Keitel and his fellow low-lifers in order to rescue a 13-year-old child prostitute played by Jodie Foster. Taxi Driver formed part of the delusional fantasy of John Hinckley Jr. His assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan was reportedly designed to impress Foster, with whom he had become besotted. The film is beautifully shot, the reflected street scenes of a rainy, neon lit and grimy New York City intense and dreamlike at the same time.

What was the greater injustice? Scorsese being beaten for Best Picture and Best Director by Robert Redford and his Ordinary People in 1980; or being dudded again in both categories 10 years later with Goodfellas by another first timer, Kevin Costner and his Dances With Wolves. Great films both, but not as good as Scorsese's brutal black and white portrayal of world champion middleweight boxer Jake LaMotta. Perhaps the academy went a little squeamish at the graphic fight scenes or the violent abuse De Niro as Jake inflicts on his wife and caring brother/manager, played by Joe Pesci. A trimmed and toned De Niro looks the part in the ring, and in later scenes when the retired Jake, now doing stand-up, has ballooned to 100kg. Being the true method actor he is, De Niro supposedly went on a three-month binge around Europe while production shut down in order to pile on the 30kg demanded by the role. The portrayal of Jake as a flawed hero, who veers between good and bad, behaving disgracefully then seeking forgiveness, is present in many of Scorsese's films. Scorsese credits De Niro, who won Best Actor for his performance, with saving his life when he convinced the director to kick his cocaine habit to make this film.

Arguably the best gangster film made, it follows the fortunes of a Mafia clan over three decades. Ray Liotta manages to look pretty and pretty menacing at the same time, playing Henry Hill, the half-Irish, half-Sicilian kid from Brooklyn who is beguiled by local mob members into a life of crime, living the high and violent life with fellow hoodlums Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci, who won a Best Supporting Actor Oscar after stealing just about every scene he was in. The film showcases Scorsese's deft use of music - Tarantino would later show a similar knack with his soundtracks - to drive the narrative in his films, his selection of crooners, Sixties pop and Rolling Stones favourites stylishly segueing the decades. Music features heavily in Scorsese's filmography: The Last Waltz in 1978, a documentary film on the final performance of The Band; the 2008 Shine A Light, of the Stones live in concert; the 2005 biopic, No Direction Home: Bob Dylan; and one of his curerent projects, a documentary on former Beatle George Harrison. The hit TV series The Sopranos unashamedly references GoodFellas, even down to its casting. Among several recruits, Lorraine Bracco, Tony Soprano's psychiatrist, was Henry's wife, Karen, while Michael Imperioli, who plays Tony's nephew and loyal soldier Christopher, was the poor waiter, Spider, who Pesci shoots in the foot.

A remake of the 2002 Hong Kong movie Infernal Affairs, this was the one that finally landed Scorsese the Best Picture and Best Director gongs from the academy. Some would say the awards were for lifetime achievement, in much the same way Paul Newman finally landed his Best Actor prize for his reprise of The Hustler's Fast Eddie Felson in the Scorsese-directed The Color of Money in 1986. But that would be to grossly underestimate a cracking mob film, the best to date of Scorsese's collaboration with his new main man, Leonardo DiCaprio. Set in Boston, Irish mob boss Frank Costello (Jack Nicholson) plants Colin (Matt Damon) as a mole in the Massachusetts police department - which, in turn, has sent Billy (DiCaprio) to infiltrate Costello's crew. It sets up another gripping tale of torn loyalties. Scorsese richly deserved his gold statues, but many film lovers would agree that the 67-year-old auteur deserves a cabinet full of them, not just a couple sitting on the mantelpiece. Michael Reid