Feeding 15,000 people daily during the holy month has taken a lot of planning - and a lot of food. Jessica Hume reports on the logistics of iftar at the Sheikh Zayed Mosque. Even so early in the morning, the Officers Club kitchen is busy. Every room is filled with men (and some women) in white chef coats, hair nets and face masks, moving quickly and methodically from oven to counter to hot storage unit. They are working hard now, but by mid afternoon everything will be done, and once the food has been loaded on to the lorries, the hardest and busiest part of the day for these people will be over.

Georges Gebrayel is running the show. The executive sous chef walks from one room to another, checking on how smoothly operations are running, patting any one of his 120 employees on the back and thanking them for their hard work before moving on to the next station. This is not your average kitchen. Spread over three storeys in the sprawling Armed Forces Officers Club in Abu Dhabi, it operates on a different scale; today, and every day during Ramadan, 20,000 meals will be prepared for serving at the Sheikh Zayed Mosque iftar.

"It's easy," laughs Samy Ayshouh, 29, the catering manager at the club. "OK, we're so busy right now, all day actually, but this kind of event is all about planning. We plan, so it's easy." Gebrayel peers into a big metal vat. "Rice," he says. "This is where it becomes biryani." One long aisle in the kitchen is used exclusively for boiling the rice. When it is done, it is transferred in bins to the large vat where it is mixed with turmeric, cloves, cinnamon, cumin, coriander, chilli and anise.

Once the white rice has become biryani, it is scooped out of the huge vats into aluminium containers and stored in what are called hot cabinets, large enough to hold between 120 and 160 meals at a time, depending on the size of the serving boxes. "This is a combo steamer," Gebrayel says, putting his hand on a refrigerator-sized metal container. A series of dials on the side control the temperature and whether the contents should be grilled, baked or roasted. The kitchen has 12 of these machines, which can cook about 100 pieces of chicken an hour, which they do until enough to feed 15,000 is ready. The ovens begin their work at 9am and continue until 2pm, at which time the work must be finished.

Before being tossed into the cooker, the chickens are boiled in huge circular containers in a spiced stew for hours. A delivery is made early each morning, the contents of which are taken to the kitchen, cleaned, chopped, then marinated. This food will be consumed the following day. Preparation for today's meal began yesterday, and by the time the cooking begins at about 6am, the work consists largely of transferring huge amounts of the same food from one large container to another.

The kitchen staff prepares a daily menu that uses 7,500 whole chickens, 3,900kg of white rice, about 750 lambs and a whole lot of vegetables, all transported in eight lorries designed specifically for carrying hot food. Hydraulic lifts at the back of each lorry load the full hot cabinets: 12 can fit at a time. The mosque's iftar meals require 220 hot cabinets, so the lorries make multiple trips to and from the Officers Club, barely a kilometre from the site.

To ensure the meals remain hot, the lorries are equipped with electricity sockets into which the cabinets are plugged. Today, each person will receive one aluminium container filled with biryani rice and one half of a boiled chicken, salad, water, juice and bread. The food is still warm when the lids are removed, though preparation of these meals began almost 12 hours ago at the Officers Club kitchen.

Klaus Tebrake, the executive assistant manager at the Officers Club, explains that although the planning of the iftar dinners is meticulous, having other events to cook for can make matters difficult. "It's not a continuous thing, breakfast, lunch, dinner. This happens all at once," he said. "You can't start this five minutes before." Tebrake says 99 per cent of the meat and produce that goes into this iftar is sourced

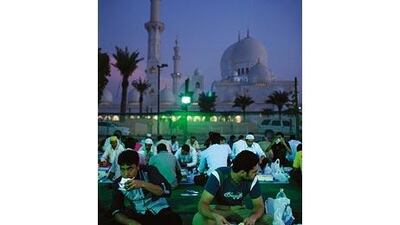

locally, although "some of the spices are from India". Though the Sheikh Zayed Mosque iftar feeds about 15,000 daily, the kitchen prepares enough food for 20,000 people. By 6pm the crowds have already begun to descend upon the mosque. Mostly labourers, they form a long line about six people wide and are ushered through the barricades by military men. On the grounds are 12 rectangular tents, each with a capacity for up to 1,000 people.

The masses arrive hungry. Inside one of the tents, a young Pakistani man runs at top speed through the entrance to a place at the far end of the tent where an empty seat remains. But he slips on the way, landing on his hands and knees, bumping into two men already seated who are attacking their rice and chicken with bare hands. "Nobody will leave here without food," Ayshouh says, standing outside one of the tents at the Sheikh Zayed Mosque. "Nobody will leave hungry."