Influenced by the trappings of steampunk, Jean-Christophe Valtat's Aurorarama builds a strange new world in the frozen wastes of the Arctic Circle, writes Jacob Silverman Aurorarama Jean-Christophe Valtat Melville House Dh96 In the April 19, 2010 issue of The New Yorker, Alec Wilkinson wrote about an expedition undertaken in 1896 by SA Andrée, a Swedish engineer, balloonist, and explorer, and two companions, who died while trying to reach the North Pole in a hydrogen balloon. Quoting from Andrée's journal, recovered 34 years after his death, Wilkinson writes: "Magnificent Venetian landscape with canals between lofty hummock edges on both sides, water-square with ice-fountain and stairs down to the canals. Divine."

Andrée was not the first explorer to be enraptured by the austere beauty of the Arctic, nor was he the first to die attempting to reach the Pole, but this sketch, written when his expedition's enthusiasm was yielding to a sense of looming danger, reflects as well as any the utopian designs often placed on this frigid region. It is also a description that wouldn't be out of place in Jean-Christophe Valtat's new novel, Aurorarama, which asks what happens when visionaries like Andrée manage to establish a utopian settlement, and whether it can be saved from sliding into dystopian ruin.

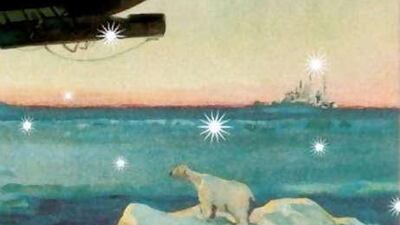

The subject of Aurorarama is New Venice, a city ambitiously founded somewhere in the Arctic by the "Seven Sleepers" and ruled by a malevolent Council of Seven. The year is 1908 AB - "After Backwards" - placing New Venice in its own indeterminate time. The Council controls the Gentlemen of the Night, a dapperly dressed, prim-talking secret police force cracking down on psychedelic drugs, an Inuit independence movement, and a gang of suffragettes led by a fugitive pop singer. They also have their eyes on Brentford Orsini, a prominent citizen who may be the author of A Blast on the Barren Land, an anarchism-inspired book calling for greater freedoms and respect of the Inuit minority. Adding to the tumult is a mysterious black airship that has docked over the city.

Already we have a sense of Valtat's inspirations, but there's much more: Herman Melville, the whole litany of fallen polar explorers (including Andrée, who appears in effigy), Coleridge's Ancient Mariner, Eskimo culture, magic, Victorian-era proto-rock music, and the kindred hallucinations of dreams/visions/ghosts/mirages (the Arctic is, after all, a desert). Wrapped in the spangled trappings of steampunk, this eclectic mix comes together, sometimes uneasily but frequently to amusing effect, as we follow Orsini and his best friend, Gabriel d'Allier, a hard-partying college professor, in their attempt to uncover the conspiracy driving the Council's behaviour.

A hybrid work that revels in its fantastical mutations - characters include hermaphroditic conjoined twins and a mythical polar kangaroo - Aurorarama is perhaps what Jules Verne would write if woken from the dead and offered a dose of mushrooms. Like Andrée's vision, New Venice is a city of islands and canals, "a city made to fulfill all appetites," "an Ideal City punished and banished to the Far North for its marble hubris". New Venice contains nightclubs, theatres, a Japanese quarter, and ravishing architecture. "Taxsleighs" and a pneumatic post take people and mail anywhere. (Along with the work of Nikola Tesla, pneumatic machines are a favourite of steampunks.)

In order to make the place more hospitable, "Air Architecture" somehow keeps the city's temperature just below freezing and a band of bird-masked Scavengers collect the trash. The Scavengers, who could be out of a Terry Gilliam movie, are a wonderful creation. Skulking around town, confined to its margins, they are the keeper of New Venice's junk- and some of its most consequential secrets. Like nation building, world creation is a messy business, and Valtat, a Frenchman who wrote this novel in a stylish English, has put a lot on his plate. As the above lists attest, he's mustering a panoply of reference material, but he's also crafting an entirely new civilisation. The consequence, however, is that we often get bogged down in the New Venice mythos; at times, it seems like every invented place, historical figure, or custom must be named. This leads to clever flourishes - some distinguished residents belong to the "arcticocracy". On the other hand, we sometimes gloss over apparently important details, such as the "Blue Wild", a disaster that once devastated New Venice but that is never fully described, or what exactly is so revolutionary about A Blast on the Barren Land (we are only allowed a few brief excerpts).

Yet if a reader is willing to deal with some inconsistencies, some references to events or people that may not be adequately explained, as well as a hefty dose of the Inuit language, this is an enjoyable amalgam of thriller, fantasy, and polar adventure, topped off with a sprinkling of anarchist intrigue. Its late-in-the-game twists are conventional and its ending improbably rosy, but Valtat's world is ingeniously imagined and peopled with an alluring cast. The novel maintains its suspense and the sense that something uncanny is just around the corner by having the chapters alternate between the escapades of Brentford and Gabriel, before their stories collide and we speed toward the novel's end.

Valtat plans to write a series of books set in New Venice, and one hopes that in future books, with his world established, he considers sometimes writing small. The novel's earlier sections show him capable of doing just that, particularly in Gabriel's exchanges with a secret policeman and with a college dean, "who would pat you on the back to choose the best spot to stab you". But the tendency to leap ahead with phantasmagorical excess - one character is beheaded, eaten by wolves, and apparently resurrected, though it may all be an hallucination - leaves some stragglers in the book's snowy wake. That same college dean is quickly forgotten; so too, for large sections of the book, are the menacing black airship and a comely student with whom Gabriel has an affair.

In July, the American publisher Farrar, Straus and Giroux released a translation of Valtat's novella 03, and the book is an example of the author's ability to extract potent emotions from sparse materials. An inner monologue of a high-school student who's fallen in love, from afar, with a mentally handicapped girl, 03 finely explores longing, obsession, and the pains of youth. Feeling insubstantial in the way so common to lonely, ruminative teenagers, the narrator describes his "existence" as "hard enough for me to maintain with any robustness". He guesses that, for the girl, his presence is "a thing she never recognized but saw as a hazy blip on the landscape of those school mornings". Through this blinkered worldview, the girl personifies a permanent innocence, one that the boy sees as an ally in his war against "the organized disaster called society" - a war to prove himself to the world, to navigate the social strictures imposed on him by peers and adults.

The girl's disability both defines his attraction to her - he envies that she's ignorant of how people can be cruel and superficial - and promises that his love will remain forever limited: "I was sad that this beauty would never be truly seen by those around her or that, even if they did see it, it could never be communicated to her or that, even if it was, it would never make sense to her." Valtat describes the girl as thin and androgynous (a subtle appreciation of gender and sexual diversity appears in both books). Her jeans "yawned and creased around an intangible absence of buttocks, as though her diminished, two-dimensional form had also been refused the trappings of femininity". This is excellent writing, well translated from the French by Mitzi Angel. It's an indication that Valtat is equally capable of creating a fully realised world by closely observing a girl on a street corner or by stitching together an extravagant tapestry.

In Aurorarama, Valtat offers "what Brentford thought about the city: that the utopia was neither given nor granted, but, quite on the contrary, had to be defended and redefined". Perhaps that's Valtat's reason to re-engage, in the promised series of New Venice books, with a place "working hard at [its] own myth". One hopes that, in developing this myth, Valtat looks to 03 and some of the more character-driven passages of his Arctic novel, for these interior worlds are as compelling as any he's created. Jacob Silverman is a contributing online editor for the Virginia Quarterly Review. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times and The New Republic

The Brothers Boswell Philip Baruth Soho Press Dh89 Hell hath no fury like literary jealousy, as was so fiercely proven in Martin Amis's The Information. Now the American novelist Philip Baruth steps into that ring with The Brothers Boswell, his imagined account of the real friendship between James Boswell and Samuel Johnson, told largely through Boswell's insane brother John, who stalks them through the streets of 18th-century London. Billed as a literary thriller, there's not actually much very thrilling about it, unless you're the sort of English professor who exclaims loudly at nuances in Shakespeare plays to show the theatre you get it. However, it is clever. Seen through a little brother's mocking eyes, the painstaking detail in Boswell's journal is, well, painful. And beyond the physical duel that's bound to transpire, the brothers base their feud on quizzing one another on words in Johnson's Dictionary of the English Language. Ultimately stumping Johnson himself, John arrives at his disgust: "He reveals so very smug a view of the universe, in which England naturally occupies the centre, and the English tongue the centre of that centre, with Samuel Johnson the center-most pin anchoring the English language entire." Touché, little brother. The Night Counter Alia Yunis Crown Dh89 The elevator pitch for this portrait of a family could be "the Lebanese-American version of My Big Fat Greek Wedding meets Bend It Like Beckham". Not to imply that it's generic but it shares with the others an affectionate, clever, funny, charming, sad, occasionally cringe-making and utterly engrossing view of culture clashes and generation gaps. The story begins with the matriarch, Fatima Abdullah, believing that she has only days left to live. Having raised 10 children, and now with countless grandchildren whom she hardly knows, she frets about who should inherit what - giving us a glimpse of each family member as she weighs up their worthiness. As in all good tales, there's a bad guy as well: a thinly veiled swipe at the ignorance of American authorities about Arabs, personified by a comically bumbling FBI agent. As a device to link the family's stories, Yunis's use of Scheherazade, the legendary storyteller of The 1,001 Nights, adds charm - yet is possibly redundant, as Yunis herself is such a great storyteller. Her acute observations of everyday life makes her characters engaging and believable - because of, rather than despite their eccentricities.