Millions of people live in Cairo, working nine to five jobs, dragging themselves through hours-long traffic jams and having to endure frequently polluted air.

But 550 kilometres away, Yahia AbdulWahab wakes up to the sound of crashing waves, eager to jump into the sea for his early morning dive. The 27-year-old first visited Dahab in 2014. “It felt like something out of a fictional universe. Every detail was magical,” he says.

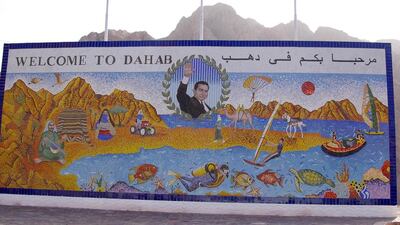

Many Egyptians have started to leave behind consumerist-driven lifestyles in cities to move to places such as Dahab, a town on the coast of the Southern Sinai Peninsula about 80km east of Sharm El Sheikh.

With a population of about 15,000, Dahab was historically a Bedouin fishing village. By the 1960s, hippies were drawn to the town and its clear waters. But Egypt’s wars with Israel ended any further development until 1982, when the peninsula was restored to Egypt. The hotel chains moved in and by the 1990s, the town was a diving centre also famous for its windsurfing.

For people like AbdulWahab, who quit Alexandria to move to the town, a typical day starts at 8am with jogging or cycling. By 9am, he goes with his friends to the Blue Hole, one of the most popular spots for freediving.

“People are warm, welcoming, caring and always draw an honest smile for reasons as simple as passing by you in the street or having a drink near you,” AbdulWahab says about the Dahab community, a blend of Egyptians, Bedouins and foreigners.

Asked what he left behind in Alexandria, AbdulWahab’s response was: “I mainly left the old me, the shopaholic self that looked for happiness in objects.”

Briton Allie Astell, 40, first visited Dahab in 2007. “The generosity of the locals, breathtakingly beautiful surroundings and peaceful atmosphere totally blew me away. I’d never been anywhere that had the same effect on me, so I was intrigued,” she says.

Years later, the freelance website manager returned, married Sofian Nour, a Sinai man and changed her name to Aliya Nour.

“Dahab’s residents – be they Egyptian, Bedouin, Sudanese, British, German, Dutch, Russian or American – all live happily side by side. There’s a real sense of community here and I love that,” she says.

However, Dahab has not been immune from the security situation on the peninsula. Bombings there in 2006 killed 23 people and there are also resentments among the impoverished local population. Many have not received any substantial financial benefits from the tourism influx and feel their plight is ignored by the authorities in Cairo.

Dahab started to become a magnet for hipsters and creative types after the 2011 protests which toppled Hosni Muburak. Economic uncertainty meant people travelled abroad less, domestic tourism boomed and more people started to know about Dahab. Social media played a role, with people who visited the town sharing photos on websites such as Instagram, Facebook and Twitter.

The town has managed to retain an authentic feel compared with the resort towns of Sharm El Sheikh that cater exclusively to foreign tourists.

For example, Cairene Nour Mourad runs Le Chat Noir, a cafe, arts and culture hub that hold regular music gigs.

Work and art spaces are also opening up, with German entrepreneur Mira Arnold establishing the first co-working space on Egyptian shores, CoworkInn Dahab. The Rainbow Community, a small spiritually-minded, ecologically-conscious group of people, also forms an integral part of society in the town. The group holds an annual dance, yoga and music festival.

“I decided to move to Dahab with no plans, until some lady decided to sell her cafe equipment and that was my chance ... and here I am two months later,” says Mourad. “Almost everyone here does something with their own hands and makes a living out of it.”

It was that “back to basics” sense of productivity that sustained Mourad’s decision to start a new life, away from “the fake artificial, commercial” Cairo. She says: “[In Cairo], you are literally working your butt off to make a living.”

She claims “fancy” careers in the capital turn people into slaves, with no mutual development, sharing of experiences and efforts. “Competition and stress to beat others instead of helping them; I left all that behind.”

The 33-year-old says Dahab is also safer for women compared with Cairo, where sexual harassment is rampant. Sherinna Sultan, who has been living in Dahab for 18 months, agrees.

“I can walk freely, wearing what I want. I don’t have to wear something extra because I want to go home safe. No more sexual harassment”.

Many city-dwellers say they want to move to Dahab.

“Dahab is my asylum. Dahab is the perfect outcome of minimal civilisation meets a back-to-basics approach. Because what kind of sane, non-masochist would want to live in a city with millions in it, taking an hour to get from home to work?” says Cairene Ahmed Omar. The programmer plans on moving to the coastal town as soon as he can find a job to work remotely.

Sara Abo Bakr, who owns a publishing house, is finalising arrangements to take this step. “There a certain kind of stress that you only find in Cairo. It brings out the worst in people. I am going in three months’ time. I can do it,” says Abo Bakr.

Aya Nader is an independent journalist based in Cairo.