If you thought today's critics could be vicious, how's this for a stinking review?

"It is impossible to convey through words an idea of this musical monstrosity. Never have I experienced a more contrived and insolent agglomeration of the most disparate elements, a wilder rage, a bloodier battle against all that is musical. At first I felt bewildered, then shocked, and finally overcome with irresistible hilarity... Here all criticism, all discussion must cease... Who has heard that, and finds it beautiful, is beyond help."

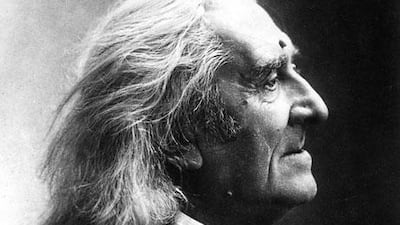

So wrote Eduard Hanslick, the powerful and much-feared Austrian music critic in 1881. The unlucky object of all this bile? A certain pianist and composer by the name of Franz Liszt. Hugely popular in his time, Liszt has been called many things - both a showy charlatan and the greatest virtuoso that has ever lived.

But while the Hungarian pianist's charismatic good looks and incredible dexterity at the keyboard have earned him an enduring place in the popular imagination, his works as a composer have frequently been disparaged and sidelined. Flashy, fiddly and vacuous - or so the black legend goes - Liszt's works have often been damned as music designed to wow the crowds rather than touch the soul.

For anyone who has actually listened to the composer's work at any length, this is patent nonsense. With the 200th anniversary of his birth this year, thankfully, this glib dismissal of Liszt's music looks set to be buried for good. Look beneath the fascinating surface of the man's life and you find a fluent, brilliantly innovative composer who stealthily helped to shape the course of classical music to come. But despite Liszt's brilliance as a composer, will it ever be possible to separate his music from the story of a man some see as the ultimate prototype of the rock star?

That story, with its heady mix of fame, romance, regret and heart-break certainly retains its pull. The son of German-speaking Hungarian parents, Liszt started his career unpromisingly as a penniless teenager in 1820s Paris, supporting his widowed mother by giving piano lessons day and night. Inspired by the example of the Italian violin virtuoso Paganini, however, Liszt soon turned himself into the most brilliant pianist of his day, adopting a slew of new hand techniques (developed singly by other contemporary pianists) that gave him a dexterity and fluency not seen previously. This gasp-inducing technical brilliance, complemented by Liszt's sharp cheekbones and long, dishevelled mane of hair, made the pianist into a Europe-wide sensation, a romantic pin-up pestered by adoring fans wherever he went. Women would faint ostentatiously in his concerts, while one lady-in-waiting is even said to have had one of Liszt's cast-off cigar stubs set into a gold locket. So great became the personality cult surrounding Liszt - fuelled by the more than 1,000 concerts he gave during his lifetime - that the pianist gave his name to an obsessive fan syndrome: Lisztomania.

This public success made Liszt a wealthy man, but it may also have bored and exhausted him. At the age of 35, Liszt gave up public performances altogether. Under the influence of his Polish mistress Princess Caroline Zu Sayn Wittgenstein, Liszt became kapellmeister at the court of Weimar, a post that gave him ample time to write music. While he remained in the public eye, the wild figure of his early years was replaced by a more sober, rueful persona. The premature deaths of two of his children in the years around 1860 brought on a spiritual crisis that ultimately led to Liszt entering a Franciscan order. In one of the more unlikely reversals in musical history, the one-time pin-up became a monk.

All this would be an interesting but half-forgotten story of 19th-century celebrity if Liszt had just been a brilliant pianist with a sideline in fiddly piano pieces. But he was far more than that. Granted, much of Liszt's concert fodder came in the form of bravura arrangements he had made of tunes by other composers, dazzling at the time but not always durable in their appeal. And with endless thundering runs and finger-stretching cascades of arpeggios, some of Liszt's original music is a poisoned gift to the melodramatic pianist, sounding dazzling but trite in the wrong hands. The best of his music, however, is a revelation. The passionate lyricism of Liszt's works recalls Romantic contemporaries such as Schumann, but they also have undertones of Italian Bel Canto and thematic similarities with his French contemporary Berlioz that make them less uniformly Germanic. Intensely atmospheric and often moving, Liszt's masterpieces remind you how exciting classical instruments can be without sacrificing dignity or emotional pull.

They can also be startlingly innovative. While many of Liszt's contemporaries - Brahms chief among them - believed in sticking to forms perfected by their great idol Beethoven, Liszt pushed in new directions. He also revered Beethoven but experimented with new forms, most notably the one-movement symphonic poem. This bold fusion of symphony, overture and sonata broke new ground by ditching preconceived ways of developing a musical theme. Instead, they were built around musical motifs -recurring tunes that suggest a particular subject - a technique that became a mainstay of Liszt's younger contemporary and future son-in-law, Wagner.

Like Wagner, Liszt also pushed at the boundaries of tonality (i.e "tunefulness"), though he gets far less recognition for doing so. Late piano works such as his spirited but ghostly Czardas Macabre dance around on and sometimes skip over the borders of conventional western melody, creating expressive discords that sound unexpectedly modern for the work of a Victorian. Even darker, Liszt's La Lugubre Gondola was written after a premonition of Wagner's death in Venice (he died two months later). Ditching complete tonality, Liszt's piece has a dying fall, permeated with an atmosphere of desolate regret created by a slow, circuitous descent of notes. Slipping delicately in and out of their minor key, this descent hints at the image of unanchored funeral boat as it does so. While traditionalists such as the critic Hanslick loathed pieces like this, they are as far away from the image of the flashy crowd-pleasing showman as you can get.

Liszt's best work can be delightful and sunlit as well as melancholic, however. In Les Jeux d'Eau de laVilla d'Este (water fountains of the Villa d'Este) from his triple piano suites Années de Pelerinage (years of pilgrimage), he creates a stream of floating, rippling notes that suggest brilliantly the cool, dancing water fountains of its title. In its dreamlike delicacy and charm, this piece sounds far more like Debussy than Wagner, and in fact proved to be an impression on the French musical impressionists who rose to fame after Liszt's death. It's possible, alas, that music of such ephemeral lightness and brilliance will always take second place in the Liszt legend to stories of his swooning fans and womanising. But as this year's anniversary wave of commemorative concerts and album releases breaks over us, hopefully the forward-looking talent of one of the 19th century's most intriguing composers may edge a little bit further into the light.