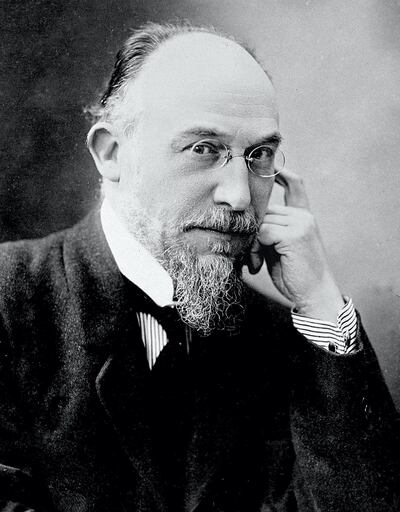

By any measure, Erik Satie was an eccentric.

This was a composer who wore identical velvet corduroy suits every day for 10 years; who said he only ate white food; who was friends with some of the most important names in European culture – Picasso, Debussy, Ravel, Poulenc. Yet he lived not just in squalor, but in isolation, too. On his death in 1925, friends finally went to his house – a place he had not invited visitors to for 27 years – and found buried among hoarded umbrellas and newspapers two grand pianos … one on top of the other.

And yet when the Camerata Salzburg orchestra play his Gnossiennes as part of the first concert of this year's Abu Dhabi Classics season, one might be forgiven for wondering where his reputation for maverick quirkiness and hugely influential surrealist music comes from. It's quiet, achingly melancholic stuff; quite beautiful in its slow intimacy and, probably because No.1 and No.2 have soundtracked any number of French art-house movies, it's now redolent of a certain kind of dark Parisian backstreet.

Satie's notes to No.6 suggest it is played "avec un conviction et avec une tristesse rigoureuse" – with conviction and a rigorous sadness. Quite.

But – and this is key – when the opening phases of Gnossiennes No.2 creep through Emirates Palace, some might be reminded of jazz great Miles Davis (who borrowed its phrasing on the track Freddie Freeloader from his album Kind of Blue). It was Satie's later work that would embolden the likes of Terry Riley, Philip Glass and Steve Reich, but listen more closely and you can hear the influence and ideas of the Dadaist, Avant-garde and Surrealist movements in Gnossiennes, too.

Listening to these pieces in 2018 – or indeed to Satie's equally famous piano works from Gymnopedies – it seems remarkable that these tranquil, reflective "pop songs" were groundbreaking at the time. But it's worth giving pause to appreciate their minimal quality. All pretentiousness is stripped out, there is no sentiment, or indeed huge significance to the music. The turn of the 20th-century was a period where Satie was railing against the excesses and grandiosity of the Wagnerian age and making simplicity exciting again.

Satie was also enjoying baiting the classical music establishment. He once composed a single page piece – Vexations – and instructed that it must be played 840 times, very slowly. "In order to play the theme 840 times in succession, it would be advisable to prepare oneself beforehand," he wrote.

It was nearly 40 years after his death until anyone even tried it (admittedly Vexations wasn't publically published in Satie's lifetime). That man was John Cage, the leading composer of the American Avant-garde, and he gathered together pianists in New York – including John Cale from the soon-to-be founded Velvet Underground – for an 18-hour music marathon. Legend has it that as the final note rang out, someone shouted "encore" – and this may be because it was written so fiendishly it had a melody that made it nearly impossible to remember, or indeed hum.

As for Cage, he said: "I had changed and the world had changed,". While that might sound like a heady claim, it is true that a lot of Satie's visionary experiments in music became precursors to some of the most interesting 20th-century art. Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen and even Brian Eno have often been lauded for their approach to instrumentation, but the music Satie composed for the ballet Parade (written by French poet and artist Jean Cocteau and designed by Picasso) was scored for typewriters, aeroplane propellers, ticker tape and a lottery wheel.

It’s significant that the term surrealism was actually used for the first time in the programme notes for this 1917 piece. And Satie was at the heart of the movement. “It’s not a question of Satie’s relevance,” said Cage. “He’s indispensable.”

And, amusingly, he is even partly responsible for the elevator muzak that unfortunately blights our modern existence. Satie preferred to call his experiments in making music that people would hear but not listen to “musique d’ameublement” – furniture music – and at the premiere of these works in 1917, during a play by Max Jacob, performed in Paris, the programme notes asked people “to take no notice of it and behave … as if it did not exist.” Of course, they did take notice because it was by Satie, and these short pieces repeated into an endless loop would again be lauded years later by, effectively, every minimalist composer the world over, including John Cage.

The point Satie was making with “musique d’ameublement” is that music can have many different functions. It doesn’t have to exist purely to enthral concert halls – although it will at Emirates Palace. What might have seemed surreal back in the early 20th century now makes perfect sense.

The Camerata Salzburg orchestra will play Satie’s Gnossiennes on Friday at Emirates Palace, Abu Dhabi, at 8pm. Tickets cost from Dh50. www.abudhabimusic.ae

_____________________

Read more:

Sound affects: the growing popularity of ambient music

The world's biggest book sale is coming to Dubai

The Baghdad Noir anthology paints a city both brutalised and inspiringly resilient

Dubai Opera announces new season of shows: here are 6 to see

_____________________