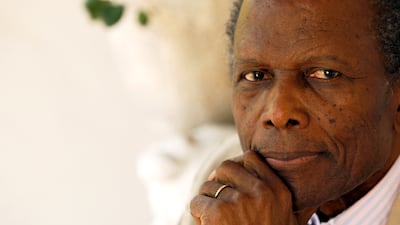

Sidney Poitier, the first black man to win an Academy Award in the best actor category, and probably the first fully fledged black Hollywood A-lister, died on Thursday night aged 94.

Poitier, the son of Bahamian tomato farmers, will be remembered as an actor, activist, humanitarian, and even a diplomat after serving as the Bahamian ambassador to Japan from 1997-2007.

His death at his Los Angeles home was announced by the Bahamian government, with Deputy Prime Minister Chester Cooper saying Poitier “did so much to show the world that those from the humblest beginnings can change the world”. No cause of death was given.

The actor was born prematurely on February 20, 1927, in Miami, Florida, while his parents were on a trip to the US selling their tomatoes. His unexpected early arrival meant that he gained US and Bahamian citizenship.

His life was often something of a contradiction. He was a trailblazer for generations of black actors to come – Selma star Daniel Oyelowo described him to ITN News on Friday night as “a pole star of what is possible” — yet Poitier once turned down the role of Othello as he didn’t want to be typecast as a “black actor".

He would publicly muse later in life over how much of his success may have been down to a form of self-congratulatory tokenism on the part of the Hollywood machine.

Opening the door for black actors

Rising to prominence in the 1950s and '60s in films that frequently dealt with thorny topics such as segregation and mixed-race marriage, he reinvented himself in the '70s as a director of comedies including Stir Crazy and Uptown Saturday Night as the civil rights movement became increasingly confrontational and his largely amiable black characters fell out of favour with increasingly politicised audiences.

Poitier would later describe as “devastating” a 1967 article in which African-American playwright Clifford Mason described his characters as “antiseptic”.

A committed opponent of authority, particularly where he saw it perpetuating injustice, Poitier would go on to receive both a knighthood from Britain's Queen Elizabeth II in 1974, thanks to his roots in the formerly British Bahamas, and a Presidential Medal of Freedom from former US president Barack Obama in 2009.

Perhaps his greatest strength was his ability to bridge these types of gaps – between black and white audiences, authority and rebellion, and social commentary and knockabout comedy. This was all the more impressive in an era when the actor himself noted that “Hollywood had not kept it secret that it wasn’t interested in supplying blacks with a variety of positive images.”

From humble beginnings

Raised on Cat Island in the Bahamas before the family moved to the capital of Nassau after storms wiped out their crops, Poitier recalled in interviews that it was only after this move that he consciously saw cars or electricity. Aged 15, he went to live with his brother in Miami, where the actor later recalled encountering racism for the very first time.

After spells in Atlanta and the US military, by 1945 Poitier was living in New York, where he unsuccessfully auditioned for the American Negro Theatre. The theatre’s co-director, Frederick O’Neal, said he could neither read nor speak his lines and told him to find work as a dishwasher.

He did just that, and with the help of a friendly old waiter, copies of The New York Times, and a trusty radio, he learnt both to read and to soften his Bahamian accent.

His next audition for the theatre group was successful, and while serving as understudy to Harry Belafonte he was spotted by another Broadway director and cast in an all-black production of the Greek drama Lysistrata.

The tough times were by no means over for the young Poitier, however. In his autobiography, he recalls that he was tone-deaf and could not sing – problematic in an era when stage roles for black actors were largely confined to the all-singing, all-dancing minstrel.

A leap of faith for Hollywood fame

In 1949, he made the decision to become a film actor. His performance in the 1950 film No Way Out, in which he played a newly-qualified doctor confronted by a racist patient, brought him to the attention of the studios and his breakthrough came in Blackboard Jungle in 1955, in the role of a disruptive pupil in an inner-city school. This film was one of the first to feature a rock’n’roll soundtrack, courtesy of Bill Haley’s Rock Around the Clock.

Poitier received his first Oscar nomination three years later for his role in The Defiant Ones, in which he starred opposite Tony Curtis as two escaped prisoners shackled together in the Deep South. Curtis insisted the two were cast as joint leads in the film, which was certainly forward-thinking for the time, though it may ultimately have cost Poitier his first Oscar. Both were nominated for Best Actor, but their vote was split and David Niven walked away with the award for his role in Separate Tables.

In 1963, Poitier would finally pick up the coveted award for his role as an itinerant handyman who helped a group of nuns build a church in the Arizona desert in Lilies of the Field, and a golden era would follow.

His career-high came in 1967, when three hit films made him Hollywood’s most bankable star.

The British hit To Sir, with Love cast him opposite Lulu as an immigrant teacher in a tough London school; Norman Jewison’s classic mystery In the Heat of the Night introduced audiences to detective Virgil Tibbs and immortalised the line “they call me Mr Tibbs,” and the comedy Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, one of the first Hollywood films to feature interracial marriage, found a young middle-class white woman played by Katharine Houghton taking her new husband [Poitier] home to meet the parents. The film was shot at a time when interracial marriage was still illegal in 17 states.

As a wave of anger, protest and riots spread across the world from 1968, it’s fair to say that Poitier’s star would never shine as bright again. He had brought a number of previously taboo topics to screen, but their usually inoffensive treatment seemed dated in this angry new world. Nonetheless, he had successfully, and almost single-handedly, normalised the very idea of a black face in a lead role.

In the 1970s and '80s, Poitier abandoned acting in favour of his directorial work. But following his final film as director, 1990’s Ghost Dad, he returned to screens in a number of lower-profile, but critically acclaimed roles, such as in the 1996 sequel To Sir, with Love II (directed by Peter Bogdanovich who also died this week) and the 1997 biopic Mandela and de Klerk.

Poitier’s films may not have featured the righteous anger of Do the Right Thing, the cutting satire of Get Out, or the sheer sense of empowerment of Black Panther, but would any of those films exist without him? Perhaps, but probably not yet.