For most of his 39 years, Malcolm X divided people, and he revelled in it.

Black Americans, especially the urban poor, applauded his attacks on white and black elites. For white America, he was a cocky demagogue whose abrasive rhetoric made him easy to hate.

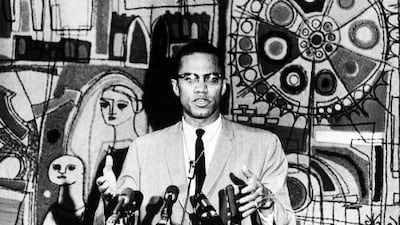

Yet by his death, X's commanding oratory was drawing crowds from Harlem and Harvard to Cairo. The Autobiography of Malcolm X, co-written by Alex Hayley and published after X's assassination on February 21, 1965, was a blockbuster. Spike Lee's hero-worshipping 1992 biopic polished the icon for a new generation. And we all know that X has become an icon. Rappers took to his oversized confidence and angry wit, and wore the oversized T-shirt. Even the US government, which shadowed him, wasn't immune, issuing a Malcolm X postage stamp in 1999.

Malcolm X doesn't threaten anyone these days, yet the late Manning Marable, with his book, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, entered a tangle of rumour and legend in examining his life. Much of the legend was spun by X himself. Was he a gifted showman, or did the high-school dropout speak from the heart? Was there another side to the shrewd man who, when John Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, quipped that "the chickens have come home to roost"? X barely had time to consider his own words: less than two years later, he would be shot dead himself.

Marable's title refers to X's evolution from lost youth to delinquent to prisoner to religious figure – he joined the African-American religious movement Nation of Islam while in jail in the early 1950s – to budding leader. Probing beyond X's own version of that process, Marable's comprehensive and complex portrait of X is less of a romance of redemption than a rigorous reality check that brings the contours of his memoir into closer focus. The criminal past of the man born Malcolm Little is, in Marable's version of events, less vicious and more amateur than the Autobiography would have readers believe.

X’s ascent wasn’t a clear trajectory, Marable writes. As his public life flourished, his marriage suffered. He neglected his young family and was unfaithful to his wife with assistants. When he was murdered, he was broke, homeless (he had fallen out with the Nation of Islam, whose enforcers then firebombed his house, from which they were trying to evict him) and haunted by the belief that the movement’s leader, Elijah Muhammad, had ordered his death.

Marable reconstructs the assassination with all the drama and despair of that cold February afternoon. X was due to speak at the Audubon Ballroom on Broadway, where Nation of Islam recruits had planned their attack the night before. He ordered his security men not to check the crowd for weapons, and three men opened fire when he took the stage. Only one, a man called Talmadge Hayer, was caught, while two men who, Hayer later claimed, had not even been there were convicted along with him. Marable maintains that one William Bradley (now known as Al-Mustafa Shabazz) fired a shotgun into X’s chest, as stated by witnesses at the time, but was never charged and lives in Newark, New Jersey, where he recently appeared in a campaign advertisement for that city’s mayor.

X’s murder is just one of the doors that Marable’s exhaustive biography opens, though he will never see what comes of it, as the author, a professor at Columbia University, died last month after a long degenerative illness. However, his research can be viewed at The Malcolm X Project at Columbia University, www.columbia.edu/cu/ccbh/mxp/.

As comprehensive as Marable’s reconstruction of that event is, historians still lack half of the existing FBI records that might establish the complicity or otherwise of law enforcement in X’s killing. Based on the available evidence, Marable argues that, even if law enforcement did not actively take part in the murder, its agents stood aside when it happened. “It was not so much a conspiracy, as a convergence of interests,” Marable said in a radio interview on the 40th anniversary of the assassination.

Another mystery around Malcolm’s death is the failure to prosecute Bradley, a career criminal who served time in prison on another charge and was later honoured for his past as a young athlete in Newark, New Jersey.

There are also questions about the role of Louis Farrakhan, the Nation of Islam minister who replaced X at the mosque over which he presided in Manhattan and later moved into X’s home. In early 1965, Farrakhan denounced the insubordinate X as “worthy of death”. But beyond noting that Farrakhan was “the main beneficiary in Malcolm’s assassination” and citing “his central role in advocating his death”, Marable found no direct evidence of Farrakhan’s involvement. The historian faults Farrakhan “for his ambition, not direct involvement in the crime.”

Some additional light might be provided by unpublished "lost chapters" of the Autobiography, which were purchased at a 1992 sale of papers from Haley's estate by the Detroit lawyer Gregory Reed. In an interview, Marable said he had been allowed to view the pages for 15 minutes. Reed, reached in Detroit, said the annotated papers included discussions between X and Haley about names being changed to avoid the risk of libel suits. Reed also noted that the chapters included an economic plan drafted by X for black empowerment.

Negotiations now under way could lead to the “electronic publication” of the chapters within months, Reed said, hinting that his decision had been accelerated by the publication of Marable’s study.

More details are sure to surface, but Marable’s definitive biography is now the standard by which scholars can evaluate, not just what Malcolm X said, but what generations of others have said about him.

Follow us on Twitter and keep up to date with the latest in arts and lifestyle news at twitter.com/LifeNationalUAE