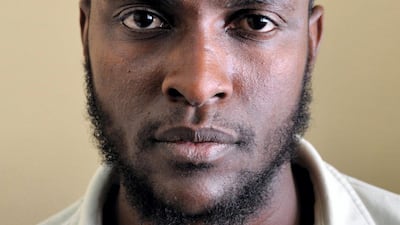

Mohammed El-Gharani was an adventurous 14-year-old with big dreams when he was arrested in Pakistan in the wake of 9/11 and transported to Guantanamo Bay, the US military prison in Cuba, where he was held without trial for eight years.

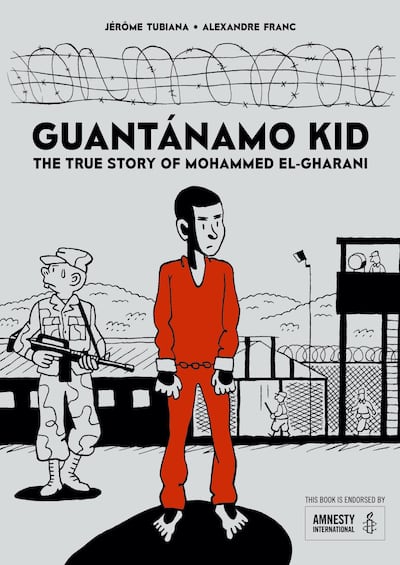

He was one of Guantanamo Bay's youngest prisoners and one of the few Africans to be held there. In 2009 he was declared innocent by a US court and released. He has recounted his harrowing story in graphic novel form in Guantanamo Kid, The True Story of Mohammed El-Gharani, to journalist Jerome Tubiana.

Guantanamo Kid, recently published in English, fits into the timeline of the history of the greater Middle East and its relations with the US and Great Britain that has been superbly told in a number of graphic novels including Best of Enemies, A History of US and Middle East Relations by historian Jean-Pierre Filiu and artist David B; Joe Sacco's work; and in Marjane Satrapi's volumes of Persepolis. Mohammed El-Gharani's personal story is not only heart-wrenching in itself, but it is also a symbol of the human fallout of decades of failed foreign policy on the part of the US.

El-Gharani's story: from Madinah, Saudi Arabia to Guantanamo

The story begins in Madinah, Saudi Arabia, in the late 1990s when El Gharani is still a child and works as a street trader. Although El Gharani was born in Saudi Arabia in either 1986 or 1987, his family was from a nomadic Saharan community from northern Chad that had emigrated to Saudi Arabia following a severe period of drought.

Despite having only a few years of private schooling behind him because of educational restrictions on non-Saudi citizens, El Gharani is bright and entrepreneurial, and with a Pakistani street trader, decides that he needs to learn English in order to realise his dream of becoming a dentist.

His friend encourages him to travel to Pakistan to live with his family and study. Although his parents are against the plan, El Gharani is street smart and determined, and with money he has saved, he manages to acquire a false passport. He takes a plane for the first time, to Karachi, where his friend's family pick him up and take him in.

Up to that point, all goes well, but two months after his arrival in Karachi, 9/11 happens. Then, in a dire example of being in the wrong place at the wrong time, El Gharani is picked up by the Pakistani military in a raid on the mosque that he attends on Fridays. The false name on his passport is the same as that of another suspect of 9/11.

He is asked if he is a member of Al Qaeda and when he says he isn't, he is interrogated. Held with other detainees, they learn they are to be transferred to the US. El Gharani is hopeful, because as a typical teen, he says in the book, "I loved watching old cowboy movies … I believed what I had seen in the films, that Americans were good people. I would have the right to a lawyer. Maybe they would even let me study in the US before sending me back to my parents."

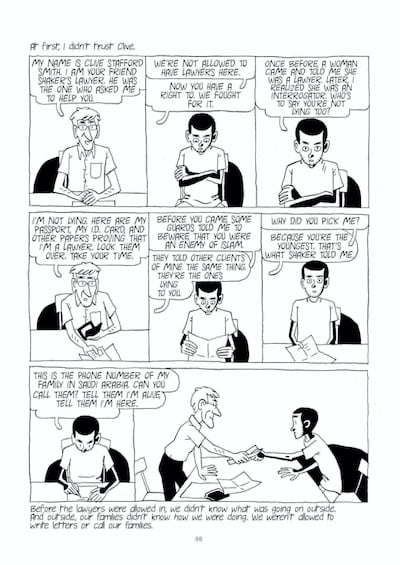

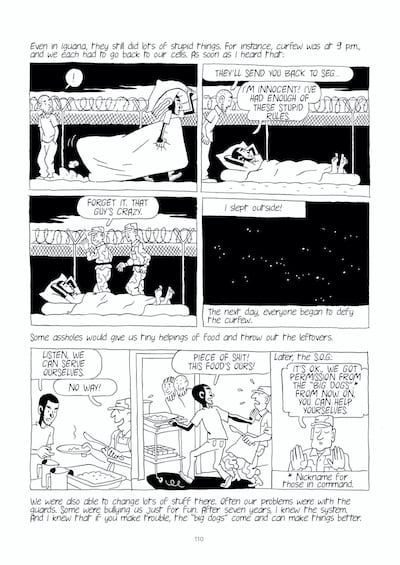

El Gharani's teenage years are cut tragically short when he arrives at Camp X-Ray where the first prisoners were held, and they are given two buckets, one for water and the other for excrement. They are later moved to Camp Delta, a permanent structure. Despite claiming to have been regularly beaten, tortured and subjected to racial harassment by soldiers, El Gharani, who twice attempted suicide, also fights back, often with the impulsiveness and mischievousness of a rebellious adolescent, earning him a reputation as a troublemaker. But he is considered lively and generous by other inmates and befriends some of the guards, teaching himself English, albeit "a redneck English with Guantanamo slang," said Tubiana at the book's launch in London.

When El Gharani told his story to Tubiana nine years later over a period of two weeks, the way the two met was improbable, and their collaboration lasted for eight years until the original publication of the graphic novel in French in 2018. They are still in touch today. Tubiana, who is a specialist on Sudan, South Sudan and Chad, was in Chad in 2010, shortly after El Gharani had been released. Because Saudi Arabia did not consider him a citizen, El Gharani had not been sent back to his family, but to Chad, where he had never lived before. An American journalist contacted Tubiana, asking if he could inquire about El Gharani's whereabouts.

After getting help from Reprieve, the human rights organisation that fought for El Gharani's release, Tubiana located him and little by little gained his trust. The US journalist "gave up on doing the story, so I asked him for permission to do the story myself, which he graciously gave me," said Tubiana, who first published several long-form articles on El Gharani's experience. It's important to mention that El Gharani's account is often interspersed with humour, as Tubiana concurs: "We spent time laughing together. Mohammed is very resilient and said he preferred to talk about the absurdity [of his situation]."

Backed by Amnesty International to turn the story into a graphic novel, Tubiana and his editor finally settled on the illustrator Alexandre Franc, whose simple black and white pictures convey the dark and absurdist tale in a bold, graphic style. "I wanted it to be very accurate in words and representation," said Tubiana. "I knew people would challenge the authenticity of Mohammed's story."

Alexandre Franc added that he purposefully didn't dwell on torture scenes because he wasn't sure that by drawing them, it added to the text. The result is that Guantanamo Kid conveys an utterly compelling story about human resilience, never victimising the inmates. But El-Gharani's story doesn't end with his release.

Little relief: life after Guantanamo

There is no happy ending, but rather a series of continuous incidents as he navigates the African continent in search of stability, his young body severely damaged by years of deprivation, with various governments still considering him suspicious.

Tubiana has added a ten-page account written in 2017 of El-Gharani’s current situation: he is still bearing the brunt of political repercussions following his imprisonment, but he is also married, with children, one son named after his fellow detainee and friend, Shaker Aamer, a UK resident who was held in Guantanamo Bay for 13 years before he was released without charge.

Despite the fact that it took eight years for the graphic novel to be published, Tubiana says the timing is good. “There are 40 detainees in Guantanamo who have more or less been forgotten. And for Mohammed, the book is a good safeguard because he is still in danger of being seen a security threat.”

Like other documentary graphic novels, it's possible that Guantanamo Kid will be used in secondary schools, which would greatly please El Gharani, said Tubiana. "Mohammed was a teenager in Guantanamo, and he was keen to be read by kids his age. Many former Guantanamo prisoners would dream to speak in schools."