Growing up, one of the largest figures in Isabella Hammad’s life was a Palestinian man she had never met. She loved to listen to her father tell tall stories about his flamboyant grandfather Midhat; born in Nablus at the end of the 19th century, he was a fully paid-up Francophile with a hilariously complicated love-life.

“The stories were always funny,” she says now. “But I wanted to find out more about him, and when I did, there was a much more complex, sadder tale there. So much pathos. Actually, Midhat was a very sensitive man.”

So, as soon as Hammad, who was born in London, felt able, she began to map out the fictionalised story of Midhat’s life, which then became one of this year’s most eagerly awaited debuts.

As Zadie Smith has already said, The Parisian is a "sublime historical epic", as it begins in 1914 with Midhat leaving Nablus – now in the Northern West Bank – for Montpellier in France, to study medicine. He brings an exoticism to university life, becoming a "famous Oriental guest", an Arab in wartime Europe.

But despite falling in love, his struggles with identity and longing for a place that can never be his own, means that he flees to Paris and then returns to Nablus at the end of the First World War, where his father demands he conform with traditions once more.

Midhat is, by now, far too charismatic to do exactly as he is told – and with the Arabs fighting for independence from the British after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, there's a huge political backdrop to The Parisian. As, of course, there is with any story about Palestine.

“Unfortunately – and maybe even ridiculously – it’s an inherently political act to write about Palestine in the West,” Hammad agrees. “So I knew what I was taking on. Of course, after 1948, the Palestinian condition is defined by a specific struggle against an occupier, but I was interested in trying to work out who Palestinians were before that had become the case, when the future was ahead of them, and there were many different possibilities. The early 20th century was a period of rupture and change, but things weren’t necessarily set.”

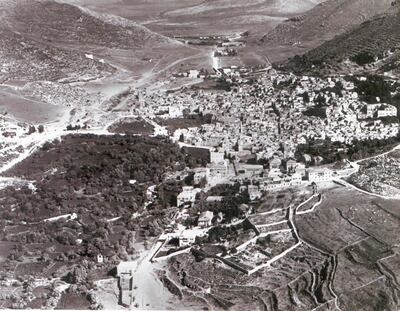

Hammad, 27, discovered those possibilities first-hand when she travelled to Nablus with her grandmother, as The Parisian was first taking shape. It was a vivid experience: she spent a lot of time with "family, old people, historians; meeting lots of people and hearing their stories", she says. Some still had memories of the real Midhat, "al-Barisi", and her childhood imagination was fired all over again.

“Nablus has always been a place of political agitation and resistance against the occupier, whether that be the Ottomans, the British or modern-day Israel, and Midhat would have been very unusual there,” she says. “But how would he have dealt with that as a complex individual? Because he is Palestinian, he doesn’t really have the freedom to define himself. Outside Palestine, he is having to constantly represent his people in some way. Inside Palestine, there is a national struggle and he is wondering around in coloured ties, dreaming of France.”

Hammad thinks that this pressure Palestinians feel to speak for an entire country continues today. She jokes that a friend of hers now tells a room he is Palestinian before he says his name, just so he can get that conversation out of the way.

As the child of a British-Irish mother and a Palestinian father who has just written a book partly set in Nablus, Hammad knows she will always be asked questions about a place she has only ever visited. But her experience is completely different to anyone else's. She can tell a story, but not the story – after all, there is no easily definable Palestinian experience.

“First of all, I want to tell a good story that will stay in people’s memories,” she says. “But I hope all novels, whether they’re historical or not, open a space in your head for things you might not have considered before. So, with my book, if that helps people to imagine this period in Palestinian history or Nablus, that would be wonderful.”

And although Zadie Smith compares The Parisian to the serious 19th-century realist fiction of Gustave Flaubert and Stendhal, scratch below the surface and there are plenty of contemporary resonances, too. As Hammad was finishing her debut, it was the 100th anniversary of the Balfour declaration, when the British government first committed itself to the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. The crucial line being: "nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of the existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine".

In Hammad’s novel, this uncertainty about what Palestine might be and who Palestinians are is played out in the frenzied discussions Midhat has in Nablus; the people didn’t believe the Balfour declaration then and they certainly don’t now. “What we see today is the continuation of the events in the period of my novel,” she says. “Palestinians still have not achieved their civil and political rights.”

So it will be interesting to see how Hammad frames her next book, which she says is a contemporary story set in Palestine and London. It's also a lot shorter; there will be no maps or cast lists in the front this time. But, despite its length, by the end of The Parisian, the epic scope has been something to luxuriate in rather than be intimidated by.

As gunfire crackles from the mountains above Nablus, Midhat ponders his error in thinking France could change him. “A fantasy of virtue,” he laments, seeing instead “a whole list of mistakes … lovely, beautiful mistakes”. It’s a hard won moment of clarity for a sensitive soul who struggles with being an outsider.

“That separation between Midhat and others takes shape not only in the situation of an Arab in Europe or Europeans in the Arab world, but encounters between men and women, fathers and sons,” says Hammad. “I wanted to explore not only what it means to live with difference but maybe what happens when actually you long for it, for something other than you are now.”