Nigerian author Nnamdi Ehirim has called on publishing houses to reassess how they define the African novel and urged them to move on from the "stereotype for African literature in English", in part created by the success of Chinua Achebe's 1958 novel Things Fall Apart.

Ehirim pointed out that Things Fall Apart, which follows the life of a wrestler in a fictional Nigerian clan, had become the "metric" used by English-language publishing houses to gauge the potential success of a novel by an African writer.

"They'd say, 'How does this resemble that novel?'" said Ehirim on the opening day of the Sharjah International Book Fair. "In a way, while Things Fall Apart was ground-breaking, it also limited the scope of [which] African novels were published in Europe. We have to be responsible for choosing our own narratives."

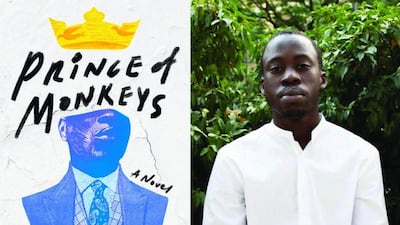

Ehirim, whose debut novel, Prince of Monkeys, was published earlier this year, added that "we shouldn't set a boundary on what the African novel is", lest we prevent it from expanding "as much as it can".

“When you [talk about] the ‘African novel’, for me, from an English speaking country, the African novel means [one thing] and for those from a French speaking country, the African novel is totally different, they have a different canon of literature and different icons,” he said. “And I’m sure in the Arabic speaking parts of North Africa, the African novel is very different, with different narratives, different stories and different themes. So the African novel is very broad.

“There are authors who write in Spanish from both Latin America as well as Spain. But you don’t label the Latin American writers as Spanish just because they write in Spanish,” he continued. “Likewise, there are many African authors settled in other countries. Why label them all as African? Every one of us have our own identity.”

Ehirim, who was speaking on a panel with Eritrean author Haji Jaber, also suggested that more could be done to translate Western literature into local dialects. “We should look to have stories in our languages,” he said “And be able to read Shakespeare and the French canon in our local languages as well.”

The rise of social media is having a positive impact on the African literary landscape, said Ehirim, who pointed out that many writers can now build their brand without a deal from a publishing house.

“Social platforms allow [writers] to create a brand,” he said. “So even before you have access to big publishers, you can still write stories on Facebook or Twitter and now people write on Instagram.”

But Ehirim warned that writers still needed to get out and explore the communities they want to represent. “Good literature is not created in isolation,” he said. “Not a lot of good stories are written by writers who sit on their own and write. You have to engage with the place you’re writing about and engage with the characters and share their stories. It is a very collaborative process.”

The Sharjah International Book Fair runs until Saturday, November 9. More information is available at sibf.com