“I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this any more!” The most famous words of Paddy Chayefsky’s career were granted to a disgruntled newscaster named Howard Beale, whose rumbling dissatisfaction with the medium in which he works erupts in this transcendent moment of anger. The movie Chayefsky wrote which contains them, Network, is a screed taking up arms against the excesses of the television industry – still the most famous critique of TV yet made. And yet the irony of Chayefsky’s attack is that his take-no-prisoners style helped begin the transformation that undid his argument. We live in the world scripted by Chayefsky, but we also find that television has evolved in a manner Chayefsky would never have predicted – but which his own career anticipated.

Paddy Chayefsky made his name as a television writer, and then he made it again as a television underminer. Chayefsky had discovered his voice in the 1950s as a writer for dramatic variety shows that essentially presented new original plays every week. He was one of the first writers to make a name for himself through television and eventually one of the few boldface names among American screenwriters. What other writer, before or after, received the screen credit “A Film by Paddy Chayefsky”? Chayefsky began by writing about “common lives and humble settings”, in the words of David Thomson. He became famous for Marty, in which two hopeless single guys make aimless weekend plans (“What do you feel like doing tonight?”) and one of them unexpectedly finds love. A celebrated television programme became an Oscar-winning film of the same name in 1955 and Chayefsky himself gladly moved on to telling stories for the big screen, which he viewed as less fatally devoid of quality than its younger sibling television: “The industry has no pride and no culture. The movies, with all their crassness, can point to something they’ve done with pride during the year.” In the 1950s and 1960s, American television was still an ocean of mediocrity dotted with islands of notable achievement; Chayefsky preferred to work in the obviously superior field of feature filmmaking.

Film changed Chayefsky, or exposed the raw nerves that had been dulled by TV. Marty had been a paragon of gentle cinematic humanism, a more polished American variant on deliberately raw European neorealism. Chayefsky was the poet of the clumsily prosaic, but with movies such as The Americanization of Emily and The Hospital, he became something else entirely: a satirist with a forked tongue, lashing out at institutions (the military, the American health-care system) that he saw as fatally corrupted.

Chayefsky complained about the fate of the writer in the unforgiving world of Hollywood, but what contemporary screenwriter would have a production company that received 42.5 per cent of the net profits on a picture? Dave Itzkoff's enjoyable Mad as Hell is a simultaneously meaty and gossipy peek inside the workings of a legendary American film, in the style of Peter Biskind's Easy Riders, Raging Bulls and Mark Harris's Pictures at a Revolution. Itzkoff is a fluid writer and a solid researcher, and his book is a compelling read. If there are any minor complaints to be made, it is that Mad as Hell does not go quite far enough in exploring the limitations – and not just the strengths – of Chayefsky's vision.

Television had made Chayefsky and now, with his new film Network, he was going to do his best to break television. “Television is the most powerful communications medium that has ever existed,” he noted in one line of dialogue, later cut from the film. “Its propagandistic potential hasn’t even been touched.” Chayefsky began by picturing a lone man driven insane by television’s relentless need for spectacle and soon grasped that instead of being drummed out of the business, Howard Beale (his last name grafted from the equally kooky Beales of the documentary Grey Gardens) would make for compelling, ratings-rich television as he broke down live on air. Beale was an acid critic of American culture’s vapidity, but he was also a voice channelling Chayefsky’s average American, terrified by events far beyond their ken: “Let me have my toaster and my teevee and my hairdryer and my steel-belted radials, and I won’t say anything, just leave us alone.” Itzkoff implies that Howard Beale is merely a condensed version of Chayefsky himself, with the author, like his newscaster doppelgänger, “at his best when he was angry”.

Chayefsky went so far as to draw up a complete prime-time line-up for his imaginary network, including such appealing shows as Lady Cop, Death Squad and Celebrity Canasta. Chayefsky first pictured “a third act … in which the network becomes so powerful it is an international power of itself and even declares war on some country”, but came to realise that the fictional UBS’s iniquity was better observed on the local, not the international, front. Network executives would instead debate whether or not to have their news anchor assassinated on the air, as if this were merely another programming decision to be reached.

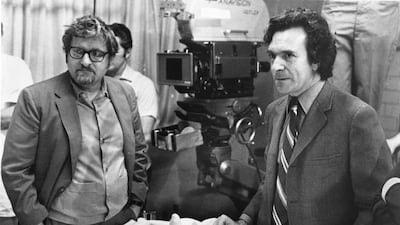

This air of hopeless moral decrepitude informed the film as we saw it. Even the style contributed to our sneaking suspicion that standards were eroding, that the centre could no longer hold. The film’s cinematographer described the film’s look as progressing from the “naturalistic” to the “realistic” to the “commercial”. The director Sidney Lumet underscored the link between technique and theme, arguing that “the movie was about corruption. So we corrupted the camera.”

The bulk of Mad as Hell follows the production of Network, leaning heavily on the reminiscences of cast members such as Ned Beatty and the production diary of Kay Chapin. After considering the likes of Henry Fonda and Jimmy Stewart (can you imagine?) as Howard, they end up casting the Australian actor Peter Finch. Faye Dunaway, playing the tough-as-nails network executive Diana, balked at shooting the love scene and only agreed when Chayefsky received permission from the studio head to fire her if she refused. Lumet and Chayefsky agreed to assiduously avoid nudity, but when the famously combative actress saw the dailies, she grumbled: “You could have shown a little more.” The self-taught Chayefsky had to be informed by a crew member that Beatrice Straight, soon to win an Oscar for her performance as the unhappy wife of the news division president, was consistently mispronouncing the word “emeritus”. He admitted he had never heard the word pronounced aloud before but had only read it in books.

Finch, married to a Jamaican woman, pleaded to be kept far away from the African-American secretaries in an office scene, for fear of igniting his wife Eletha’s wrath. Finch unexpectedly died after shooting Network and the director William Friedkin (The French Connection), who was overseeing the Academy Awards, attempted to prevent Finch’s widow from collecting his Oscar, were he to win. Some felt that the snub was racial in nature – that Friedkin was concerned about letting a black woman appear onstage as a dead white actor’s widow, even after Sidney Poitier and other African-American actors had already won Oscars of their own. Friedkin convinced Chayefsky to accept the award, but when Finch won, he graciously called Eletha up to the stage in his stead.

Itzkoff concentrates, in the later stages of the book, on the ways in which Chayefsky’s Cassandra-esque prediction of the future of TV has come true. “Where nationally televised news had been a once-nightly ritual, it has since grown into a 24-hour-a-day habit, available on channels devoted entirely and ceaselessly to its dissemination,” he argues.

At the end of the book, Itzkoff ropes in disciples of Chayefsky’s such as Aaron Sorkin to laud the great man’s prophetic ability: “No predictor of the future – not even Orwell – has ever been as right as Chayefsky was when he wrote Network.” There is much truth in this stance and if Network is not quite as scabrous or biting as it once was, this is in part because the emergence of Fox News and MSNBC have rendered satire as reality.

But there is another element of Chayefsky’s life that tells a more complex story of the relative rise and fall of artistic media. Chayefsky was a writer who dreamt of escaping the artistic ghetto of television for the freedom and rigour of the feature film. Network was, in no small part, the revenge of a former TV writer biting the hand that had once fed him, lashing out at a landscape of lowest-common-denominator programming and entertainment masquerading as news. Television was “a blossoming medium he had helped to define and popularise”, says Itzkoff, “but in two quick decades it had become hopelessly, irrevocably corrupt, devaluing truth and alienating viewers from one another”.

Chayefsky had birthed a hapless, thankless child, one better off being strangled out of mercy than allowed to go on corrupting American society – or so Network posited.

Chayefsky dreamt of a world in which the writer was king – one bearing no resemblance whatsoever to the Hollywood of the time and leading to his essentially being fired from his next film, Altered States. But if Chayefsky were to return today, young and vigorous and bursting with unfiltered, unsentimental stories to tell about American life, where would he turn but to television? Chayefsky’s truest contemporary inheritors are such television showrunners as David Simon (The Wire, Treme) and Vince Gilligan (Breaking Bad), who work with a scope and passion that contemporary American film cannot come close to matching. Network was prescient, but was only able to see a small swath of what is now the wildly patterned fabric of contemporary television. Chayefsky’s predicted future has come to pass, after a fashion, but instead of television becoming more and more of a vast wasteland, it has become the most compelling, unifying and absorbing offshoot of American popular culture.

Undoubtedly, some reality-television producer is working, as we speak, on adapting Celebrity Canasta for prime time, but this is hardly the extent of television’s capabilities. Chayefsky’s indictment of television in Network feels more personal than intellectual and as a result, it failed to imagine the ways in which television could be not only dominant, but groundbreaking.

Saul Austerlitz is the author of Another Fine Mess: A History of American Film Comedy.