Early into Hassan Blasim's debut novel God 99, the protagonist muses on Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa's claim that literature is the most enjoyable way to ignore life. Hassan Owl – whose views and experiences often mirror those of his creator – says that in his case, literature has not only provided refuge from life, it has also saved his life "since I was born in a country where every decade the barbaric level of violence has risen to higher and more grotesque levels".

That country is Iraq, where the level of violence and persecution reached such heights that Blasim was forced to leave it in 2000. His homeland has since served as the setting for his captivating short stories. His first collection, The Madman of Freedom Square (2009), plunged readers into bizarre, blood-spattered worlds in which the living and the dead navigate the horrors of post-invasion Iraq.

Blasim delivered more of the same in his second collection of stories, The Iraqi Christ (2013). It went on to win the 2014 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize – the first Arabic title to do so. A story in The Corpse Exhibition and Other Stories of Iraq (2014) has a mysterious art collective that commissions artist-agents to kill "clients" and publicly display their bodies in imaginative ways. But to what end?

The recognition he has earned for his books will have been gratefully received, since Blasim's work remains either banned or severely edited throughout the Middle East. This is, in part, because of his decision to write in what he terms "street Arabic" over classical Arabic. In the words of his alter ego, Owl: "They say my Arabic is vulgar, lacks beauty and offends religious taboos."

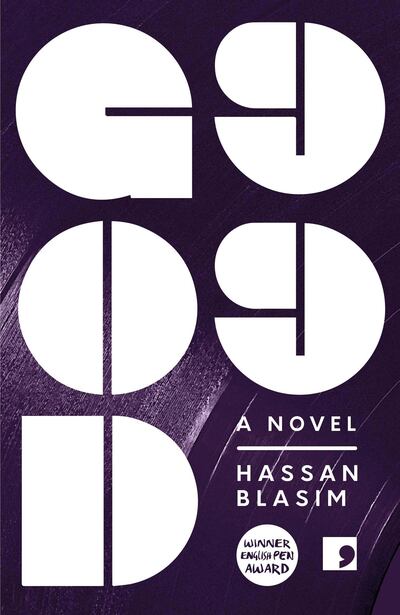

He reinforces his status as an uncompromising writer with God 99, his first foray into long-form fiction. It's an inventive debut novel that expertly depicts the devastation of conflict and the dislocation of exile. Skilfully translated by Jonathan Wright, the book blends fact and fiction, stark realism and hallucinatory Surrealism, deadly seriousness and pitch-black comedy. Sometimes the mash-up is too chaotic for its own good. However, when Blasim gets the mix just right, the effects are exhilarating.

The premise is simple yet intriguing. Owl – like Blasim, an Iraqi living in exile in Finland – devises a way to make it as a writer: he will interview 99 people whose lives have been "disrupted" by war and collate their stories in a blog. Each story is interspersed with emails from a mysterious Iraqi translator on the art of writing and the situation in "our tormented country". The book's dedication informs us that these sections are based on the author's correspondence with late friend and countryman Adnan Al Mubarak.

Owl's God 99 project gets under way with "Doctor DJ". Hadeel tells him how ISIS took over her neighbourhood and killed the man she had been married to for only two months. Compounding her pain and her panic attacks were the grisly sights and agonised sounds of the patients she tended to in hospital, the wounded soldiers and civilians caught up in clashes between the army and extremist groups. When it all got too much, she swapped medicine for music, and fled her homeland for Berlin and "the cave of techno".

Another tale takes Owl to Baghdad's Ghazal market where he hears about "YouTube Man" who sold flies there until the city fell, after which he went on a five-year robbing spree, filming everything he stole. In "Face Mask", Owl speaks with a former baker who now makes death masks, often free of charge, for the disfigured victims of suicide bombers. Even more macabre is "Ali Transistor", in which a carpenter and his friend make plans to honour a last request and construct a model of a busy vegetable market that was recently blown up by a car bomb.

In one of the most powerful stories, Blasim turns the focus on himself. "The Grasshopper Eater" comprises a retelling of the turbulent years he spent as a refugee trying to cross Europe. He and other "clandestine migrants" toil in Istanbul to pay traffickers before risking their lives on numerous attempts to cross the Turkish-Bulgarian border.

The book is at its best when it homes in on the plight of refugees. Some manage to adapt to what one woman calls “the bitter, poisoned life of exile”. Others can’t fit in and are always looking back, pining for what they relinquished: “Despite all the disasters it brought us,” says one woman, “Baghdad remains our eternal lost dream.” One of Owl’s subjects, a man who has traded working in a hammam in Iraq for a sauna in Finland, posits an argument for inclusivity over fear of outsiders: “Aren’t humans in general really migrants who carry around shattered fragments of their peace of mind deep inside them?”

Readers who relish these insightful exchanges may baulk at the book’s lurid encounters, bleak visions and meandering trains of thought. But when Blasim reins in and tones down his excess, his narrative acquires heft.

The traumatised accounts of his subjects have bite, vigour and poignancy, and his descriptions pack a punch: Baghdad "now bristles with weapons and its eyes have dark rings of fear and pain". Forget that the book resembles another short story collection more than a novel, and instead admire the individual strengths of each tale and their collective brute force.