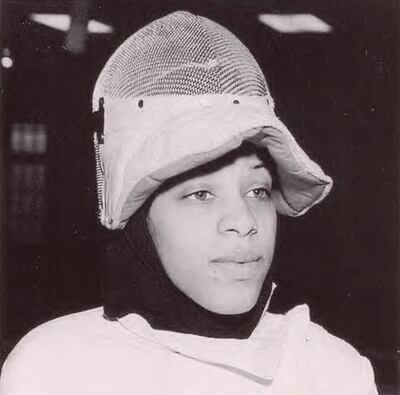

She's best known for her lightning-quick speed with a fencing sabre, but Ibtihaj Muhammad's tongue is just as sharp.

Muhammad – the first Muslim American woman to wear a hijab while competing for the United States at the Olympics in Rio back in 2016 – does not mince her words when it comes to Donald Trump.

The Olympic bronze medallist believes the current US president is on a “mission to undo every bit of Obama’s legacy”, and she’s determined to use her profile as a platform for change, just as high-profile Muslim athletes, like Muhammad Ali, did before her. “This is the most xenophobic racist time I’ve ever experienced [in America] in my 30 years of existence. It’s not easy to be a Muslim in this moment for sure,” she says. “I would argue it’s harder now than it was after 9/11 to be a Muslim in this country, and a lot of that has to do with fear.”

In was Muhammad’s fire in the belly that set her on her path to claiming a bronze medal in the fencing arena at the Rio Olympic Games.

This week, she released her memoir Proud: My Fight for an Unlikely American Dream – her way of expressing how she has managed to beat the odds her entire life. "I know there's an age-old saying about making a seat at the table," she tells me. "I don't need a seat, I'm pulling up a chair and I'm telling you I'm going to exist in this space whether you like it or not."

Read more: Notable female athletes who compete in a hijab - in pictures

Proud, which was released on Tuesday along with teen version Living My American Dream, details Muhammad's remarkable journey from an aspiring young athlete to being named one of Time magazine's 100 Most Influential People in 2016.

The challenges of life as a young Muslim woman in suburban New Jersey

She has met Barack and Michelle Obama; become a sports ambassador for the US State Department, and is part of an activist group called Athletes for Impact, of which John Carlos – the sprinter who raised his fist in a Black Power salute at the 1968 Olympics – is also a member. Muhammad wants the book to help people understand the “realities of life as a woman of colour in a sport that’s predominantly white.

“There are all these different moments in my life where it would have been easier to take a more traditional route, a lot of that having to do with other people’s misconceptions and their limitations on your own capacity,” she says. “More than anything, I hope this book serves as an inspiration to people to show that no matter what society’s limited expectations are of you, we are much more capable than we choose to know.”

Muhammad grew up in suburban Maplewood, New Jersey, where her mother Denise was a special-needs teacher and her father Eugene a narcotics detective. Her parents converted to Islam after being introduced to the religion by members of their extended family. According to Muhammad, Maplewood was so American it “literally [looked] like a stand-in for a 1950s movie set”.

Hers was one of the two Muslim families in town, which in itself led to isolation. Her hijab and her skin tone drew considerable unwanted attention, and she says she was often tormented by her middle school classmates. In her book, she references one boy asking her why she wore a “tablecloth” on her head, and another used to “torture” her by kicking her backpack so hard he made a hole in it. Muhammad sought refuge in sport. At the age of 13 she stumbled across fencing practice at Columbia High School, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Feeling at home with fencing, but alienated by her team

In her book Muhammad writes that once suited up, helmet and all, she “fit in without having to try. It was the only sport I’ve participated in where I didn’t have to wear something different”. Muhammad fenced using the epee – the heaviest of the three modern fencing weapons – until she was 16, but that changed when her coach, Frank Mustilli, saw her fire up after she was hit in practice and “roared with rage”. He moved her to the much faster sabre discipline where she excelled, and in 2005 was selected to represent the US at the Junior Olympics in Cleveland, Ohio.

This wasn’t the end of her cultural challenges, though, and as she says in the book, she was still uncomfortable being one of very few black faces in the team. It was this that prompted her to start taking instruction at a foundation run by Peter Westbrook, a groundbreaking African-American sabre fencer who had won bronze at the 1984 Olympics. Most of the students there were mixed race.

________________

Read more

Muslims of America: the photo project showcasing the diversity of Islam

Barbie makes doll of hijab-wearing Olympian Ibtihaj Muhammad

Rio Olympics 2016: Fencer Ibtihaj Muhammed looks to make history for Muslim Americans

________________

“To walk into a room full of fencers and not feel like the odd one out … felt like freedom,” she says. After graduating from Duke University in North Carolina with a major in international relations and African-American studies and a minor in Arabic, Muhammad tried unsuccessfully to get a job as a lawyer. She says one not-so subtle executive asked her if her “lifestyle” would be compatible with her duties.

On her return to full-time fencing she worked with 2000 US Olympian Akhi Spencer-El, paying her way by working at the Dollar store, a discount chain, and as a substitute teacher. By 2010 she had worked her way up the rankings and earned herself a spot on Team USA. The achievement brought with it both fandom and harassment. She notes that one man followed her after practice, accusing her of being a terrorist with a bomb. In addition to this, she’s been stopped at immigration on her way into the US, despite being an American citizen, and at the South by Southwest music festival in Austin, Texas, was asked to remove her hijab for “security reasons”. She refused.

Perhaps one place she didn’t expect to feel challenged was in the company of her teammates, but in the book, she says that’s exactly what happened in the lead-up to the 2016 Games. Mohammed claims that training times were cut out of emails, and she was unfairly labelled “lazy” by Team Sabre coach Ed Korfanty. She also says that her fellow fencing teammates would go out for dinner and not invite her, making her feel like a “second-class citizen”. She says that Korfanty offered her no sympathy during Ramadan and suggested she was “slacking off” attributing it to her fasting.

Muhammad says it became a “mental game”. She admits that she spent dozens of hours “crying and unhappy”, surrounded by people who made her feel “inferior and devalued”.

“In the end I decided that the women’s sabre team simply wasn’t ready for change – an African-American Muslim was too much difference all at once,” she writes. “I think my team viewed me as so different from themselves that they didn’t know how to relate and they weren’t willing to put the effort in to figure it out.”

Muhammad lost to France’s Cecilia Berder in the second round of the individual competition in Rio, but went on to claim bronze in the team competition. This accolade saw her become the first female Muslim-American athlete to earn an Olympic medal.

How she'll keep 'screaming from the top' of her lungs

During the Games and in light of Trump calling for “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims”, she continued to highlight her personal safety fears. Last March she penned an open letter to the US president telling him she was the “picture of the American dream”.

She’s not far off the mark there, given that she worked hard to get where she is and has benefited from that. Her success on the world stage won her a sponsorship contract with Nike, who she teamed up with to launch the sporting giant’s first Pro Hijab range. She has amassed 261,000 followers on Instagram, 62,000 on Twitter and 172,000 likes on Facebook, and last year, Mattel released a Muhammad-inspired Barbie doll as part of its “Shero” range of prominent women, complete with toy sabre and hijab.

And if all of that isn’t enough, she and her sisters have launched a clothing line, Louella, that aims to make fashionable modest garments. For now Muhammad, who is ranked seventh in the world in women’s fencing is “on a break” from the sport, but she’s not taking a break from her push for change.

“I want to always be an advocate and a voice for change, even if that means I’m the only one and I’m screaming to the top of my lungs,” she says. “If I can reach and change one mind it feels like I’ve done my job.”

Proud: My Fight for an Unlikely American Dream, published by Hachette Books, is out on July 24