It's a rare good day in Iraq's Al Rusafa district, on the outskirts of Baghdad, despite the noise, dirt, chaos and aggression. Tejaswini and Shabnam, the protagonists of acclaimed Indian author Kunal Basu's book The Endgame, have run away from a US Marines camp to flee the country. The women make it to the capital, and all is going well until a catastrophe occurs, and the book ends abruptly.

Perhaps it's a way to build up anxiety for a sequel, or simply a mechanism to leave readers imagining what could happen next, but, either way, it's an effective finish to a fast-paced novel that highlights the depravity created by war and how its repercussions can ripple across the globe.

Tejaswini and Shabnam appear to be two diametrically opposite women – the former a renowned American journalist known for her groundbreaking reportage, and the latter a trafficked girl from Bengal who was sold as a slave when she was young. There's a secret that binds them together, but also resilience and the passion to fight until the end which shines through the characters. But this isn't exactly a new story.

The Endgame is the English translation of Basu's 2018 Bengali novel Tejaswini O Shabnam. It is also set in the present day, as opposed to the historical novels he has been writing since 2001. But the accomplished author, 63, says he doesn't set out to write stories of a certain time.

"I start the writing process with a story, instead of the time I want to set a story in," he says. "The genesis of a story occurs in the deep recesses of a writer's mind, usually in a flash, and every author's journey is different. I'm attracted to various things."

We're sitting in his beautiful home in Kolkata, his walls lined with books and artwork. This is not to say there's clutter – the home is spacious enough to wander in freely, a balance that defines Basu's life as a novelist and a professor of marketing at Oxford University's Said Business School.

"My academic life has informed my writing in that I've travelled around the world and had unique experiences," he says. He was at Tiananmen Square when Beijing declared martial law in June 1989, and he's also credited with opening Cuba's first business school, at the University of Havana. Though he primarily produces fiction, Basu has also written for more than 100 academic journals.

“Writing is my preferred form of expression,” he says. “There’s something challenging and exciting about being articulate on the page. I’m stretched outside my skin, and my novels thrive on my encounters.”

This love for the written word is inherited from his parents – after all, he was born in their study. His mother, Chabi Basu, a renowned Bengali author, was in the middle of writing a book during her pregnancy.

"She thought she wouldn't have time to write once she had me, so she held me in for as long as she could, even when her water broke!" Basu laughs. "But I couldn't wait." While Basu always loved to write, he also knew that being an author all those decades ago was unsustainable as a paid career. So, instead, he pursued higher education, completed his doctorate and became an academic.

"Books were always the mainstay," says Basu. "But I didn't want to be a hobbyist. I needed a profession… and I had the licence to write as soon as I became a professor."

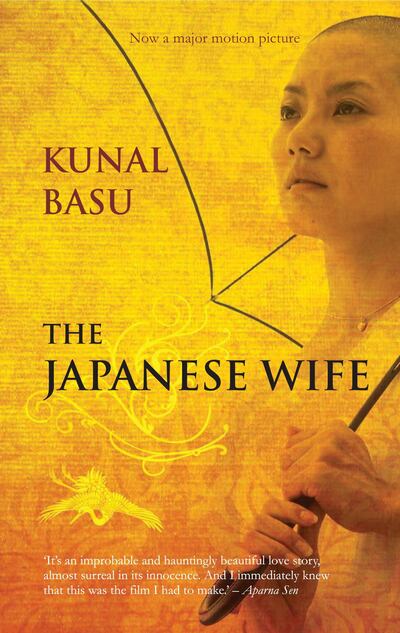

His writing career began with The Opium Clerk in 2001, which was followed by several acclaimed novels over the past two decades; The Miniaturist, Racists and The Yellow Emperor's Cure, as well as a collection of short stories called The Japanese Wife.

He also writes prolifically in Bengali, and has three other books out this month apart from The Endgame – Angel (in Bengali), Chitrakaar (the Hindi translation of The Miniaturist) and Sarojini's Mother. The Japanese Wife was adapted into a moving love story and critically lauded film by the award-winning filmmaker Aparna Sen.

So how exactly do these unique stories come to life? He muses that they usually fall into place in his mind. For example, The Japanese Wife came about 25 years after he first ruminated over it.

"I was passionately involved in activism [his parents were among Bengal's most prominent communists] and I remember I was standing on a jetty with a comrade in a village in South Bengal," Basu says. "He suddenly pointed to a man at a distance and said, 'You know, he has a Japanese wife'. And I was transfixed."

At the time, Basu recalls, he had a million questions racing through his mind – how did the two meet? How do they communicate? Does the husband know Japanese? But he did not ask any of them. He is thankful, however, that his imagination was left to run free when he wrote the short story later.

The Endgame also germinated unexpectedly. Basu travelled to a village in Bengal notorious for human trafficking to meet survivors as research for a Bollywood project. But when he was at last face to face with the women and girls, he couldn't ask them anything.

"I was staring at 14 pairs of eyes, and to my mind they blended into the face of Shabnam," Basu says. "I was filled with so much anger. All these injustices [in the book] are connected."

The strength displayed by Tejaswini and Shabnam echoes the mood of women in India today, although coincidentally, as they become the face of protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act and the National Register of Citizens. The act has led to protests across India over the past month. Women, especially, have been leading the charge in places such as the southern Delhi district of Shaheen Bagh, and the mounting sound of the female voice deeply resonates with the characters Basu has penned in his current books.

"Everything is so incredibly depressing. Early socialism has worn thin, and I'm troubled by the totalitarianism, the far-right and ugly nationalism rearing up in India. Undoubtedly, I will write fiction that addresses our times."