A child stands staring at the wall where a ladder with scrambled steps blocks his way. His features are slumped in despair. The message from this simple sketch is clear: dreams don’t flourish here, the path ahead is barred.

Another child in another picture shows why. This time it’s an infant surrounded by soldiers and tanks, their gun barrels inches from his face – the Palestinian baby born into a world of perpetual conflict. This image, which was drawn when the Gaza war broke out in 2014, was the start of a new style for Palestinian caricaturist Mohammad Sabaaneh, who has earned international recognition for his devastating portrayal of life in occupied Palestine.

It's one of more than a hundred drawings featured in Sabaaneh's new book Palestine in Black and White, a collection of his cartoons conceived during the five torturous months he spent as a political prisoner in an Israeli jail in 2013.

For Sabaaneh, who is the principal political cartoonist for Al-Hayat al-Jadida, the Palestinian Authority's daily newspaper, the only way of coping was to imagine he was "a journalist on a mission" tasked with documenting the degrading conditions faced by Palestinian prisoners.

Shut in a tiny windowless cell under solitary confinement for several weeks, he clung to his sense of self by sketching in thin air before stealing a piece of paper from his guard and cramming as many illustrations as he could onto the page.

These sketches, which form the final chapter of his book, are among the most powerful portraits he paints – raw, gut-wrenching visualisations that claw at the senses with their depiction of families torn apart, prisoners crushed by injustice and despair that life outside is simply another version of the prison. Sabaaneh recalls filing his nails against the walls to restore some dignity to his appearance. “I was ugly inside the prison, I was scared, I was tired, I was frightened,” he says.

Inside he saw a different side to the romanticised image of Palestinian martyrs. “I drew a lot of cartoons about Palestinian prisoners before I was in prison and I used to depict them as heroes like most of the Palestinian artists and cartoonists do.”

But the danger, he says, is that you “dehumanise them when you just depict them as a superhero.”

Sabaaneh, who has won several awards for his work and been published in numerous Arabic newspapers, including Abu Dhabi's Aletihad, wants to show international audiences the "ugliness" that has taken hold of both sides in a conflict that has raged for more than half a century.

Born in Kuwait, he moved to the West Bank in 2000, living first in Jenin and then Ramallah, where he still lives today. His illustrations convey how little has changed in the bloody standoff that followed the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, which forced 700,000 Palestinians from their towns and villages in an event known as the Naqba or “catastrophe”.

Today, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees, supports more than five million people in exile.

These pictures aren’t snapshots of history, they represent daily life for Palestinians, Sabaaneh told listeners during a recent publicity tour in the United Kingdom, which included an appearance at the Edinburgh International Book Festival. Flipping through a slideshow of photographs showing Palestinian homes being bulldozed and Israeli soldiers dragging screaming protesters away, he described the desperation of a situation where “the same thing goes on and on.”

His own works are a visceral response to these scenes. Chaotic and confrontational, they are unflinching in their treatment of the despair of the struggle and the downtrodden reality of the Palestinian plight.

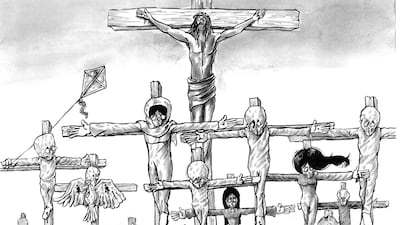

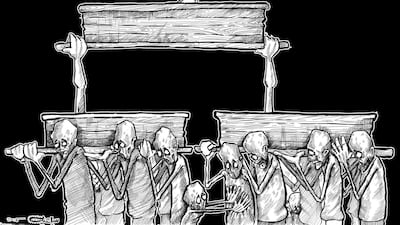

It’s not martyred heroes or defeated Israeli forces in the foreground of these cartoons. Instead, we see all of Palestine strung up on a cross, families separated by vicious coils of wire and, in one particularly poignant image, a child holding out his hands to halt pall-bearers carrying the coffins of fallen martyrs. “It is hard to look at. It should be,” writes radical comic book artist Seth Tobocman in his foreword to the book. “This is angry art, ruthless and relentless,” he adds.

No one escapes the giant prison. In another picture, a city complete with mosques, schools, shops and houses is enclosed within cell walls, the barred window allowing a glimpse of light from the world outside.

Palestinians are “oppressed by another oppressed people,” Sabaaneh says. The difference is “we have no choice”. It’s messages like these that give Sabaaneh’s work its edge, replacing heavily loaded media narratives with more nuanced insights into perspectives on the ground. These images, says Rowson, come from a commentator that is “truly on the frontline” and offer up “far deeper truths than any writer or photographer could.” In his crowded cartoons, the claustrophobia of life for five million people living on a piece of land just 6,200 km2 in size is clearly visible.

Looking at these pictures, you “feel the Palestinians under occupation,” says Marguerite Dabaie, a Palestinian-American illustrator who has written about the political cartoonist’s career. “Sabaaneh’s work is a visual reminder of how powerfully the medium can portray the inner workings of a people; his work is just as needed today as was his cartoonist predecessor’s, Naji Al Ali,” she says, referring to the celebrated Palestinian cartoonist who was assassinated in 1987.

Elizabeth Briggs, his publisher and editor at Saqi Books, agrees. “Find me a photograph that can convey these emotions as well as Sabaaneh’s work,” she says. This volume, she believes, “will shake things up” and hopefully mark the beginning of introducing more Arab cartoonists to western audiences.

But in Palestine, the cartoonist's higher profile marks him out as a target for death threats and persecution. Since the attack on French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo in 2015, when gunmen murdered 12 people, there has been a steady tightening of the censorship noose in recognition of the cartoonists' influence, he said.

Returning from a trip to the Comic Book Festival in Brussels earlier this year, Sabaaneh was interrogated for more than six hours at the border and the work he’d been exhibiting was confiscated by Israeli guards.

But even as it becomes “harder and harder” to address sensitive subjects, he refuses to shy away. “The only way we can resist now is to talk about what’s happening,” he explains.

Sabaaneh also wants to show that there is “another side to Palestine” by building his reputation as a successful artist and creating a platform for other Arab cartoonists to do the same.

Visiting the Cartoon Museum in London, he was surprised to see school children learning the skills he taught himself, searching famous cartoonists on the internet – after it became available in Palestine in 2000 – and trying different styles.

“We should give the next generation these tools,” he says, “Not just so they can use them to resist the occupation, but to allow them the opportunities that so many young people in Palestine are denied.”

_________________

Read more:

Naji al-Ali: remembering one of the Middle East's most important cartoonists

Palestinian arts and crafts that tell a story of the ages

Ahed Tamimi’s face has launched a million clicks: the hefty price of expression in Palestine

First Palestinian art museum in US opens its doors

_________________