The deep baritone voice on the phone is courteous and reflective. It doesn't sound like it belongs to a man who, for 35 years, kept the company of some of the most dangerous criminals in India. "That's the equivalent of two-and-a-half life sentences," remarks Sunil Gupta.

A former superintendent and then legal officer in New Delhi’s notorious Tihar Jail, Gupta has witnessed scenes beyond the compass of any ordinary life – such as the hanging of eight men, including the two assassins of India’s former prime minister Indira Gandhi.

Now in his early sixties and retired, Gupta has opened a window on life within Tihar, in a memoir co-written with journalist Sunetra Choudhury, entitled Black Warrant: Confessions of a Tihar Jailer.

Why Tihar Jail gained its infamy

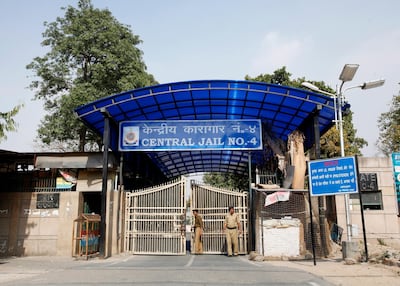

About 80 hectares in size, Tihar is India’s biggest prison complex. It has capacity for about 6,000 inmates, although the actual number of prisoners it houses is often nearly twice that. And it is almost always in the news because of its high-profile convicts. Only this month, it carried out the hanging of four of the six men behind the shocking rape and murder of a young girl on a bus in Delhi in 2012.

But what is life like behind those high walls? Gupta knows better than anyone. His story begins with him turning up at Tihar one summer morning in 1981, holding an offer letter for the post of assistant jail superintendent. See him now: he’s a fresh-faced law graduate with a desire to serve the country and to work for the reform of those written off by the world.

The first person he meets is the officer to whom he reports; the second, walking around the premises with the same liberty as the first, is “a smartly dressed man in a tie and jacket” who looks vaguely familiar.

Gupta learns this is Charles Sobhraj, the notorious serial killer, jewel thief and psychopath wanted by the police in several countries. In prison, Sobhraj wields the same sinister charisma that opened so many doors for him in the outside world. He runs drugs and liquor rackets, writes legal briefs for the uneducated, cooks his own food, and pays out huge bribes – two volumes of memoirs have made him rich – to be allowed the run of the premises.

There’s not a single law of the prison that he doesn’t flout. Soon Sobhraj is offering Gupta expert advice on how to draft replies to queries made of Tihar by the courts. The two become collaborators of sorts.

What is a 'black warrant'?

Murderers and rapists, terrorists, gangsters, drug lords and drug addicts: Gupta’s life becomes an education in all the shades of human malfeasance. Each day brings new challenges, as new inmates arrive and new networks, alliances and rivalries take shape.

Many convicts have a reputation for violence; equally, few administrators have an appetite for regular face-offs with hardened criminals. So much of the daily work of administration is done by what are called “numberdaars”, convicts who act as a buffer between the jail staff and the prisoners.

Even in this benighted world, there can sometimes appear a moment that sends a chill through the prison. A “black warrant” is one of the rarest documents to arrive in a jail. Limited only to those on death row, it is a judge’s order that is issued when an inmate’s mercy petition is rejected, indicating that he or she has no legal recourse left – and that the jail must prepare for a hanging.

Judges who issue black warrants, Gupta tells us, usually break or throw away the pens with which they do so. The jail staff inform the prisoner of the impending hanging and move him or her into solitary confinement for a week. Some convicts sink into depression; others face the end with great fortitude, especially when they feel they are dying for a cause.

'I was just a weary man doing the job that he was assigned to do'

Gupta vividly shows how Tihar is a world unto itself, a liminal space where different realms intersect: the statutes of the formal legal system, the law of the jungle practised by the most difficult prisoners, and the special privileges of money and power.

One gangster is so powerful that he manages to have two cells: one for himself and the other for breeding pigeons. Another convict is the son of a very powerful politician. When some of the country’s top legal brains are unable to save him from being sentenced in a murder case, the family buys up a five-star hotel close to the jail, just to send him food.

The hotel offers employment to the relatives of dozens of jail staff, thereby buying their allegiance. One institution swiftly overwhelms another.

In such a dispiriting environment, Gupta learns to take satisfaction in small reforms, such as the institution of a “safe zone” for those sentenced to less than six months, so they may not be influenced by the bad eggs.

Strange realities flower in jail, such as a romance between a rapist and a female jailer that ends up in marriage. Even the politician’s son, at first so contemptible in his cocoon of privilege, ends up doing some good.

A management graduate, he takes over “TJ’s” – the brand under which inmates produce clothes, furniture, and baked goods – and greatly expands the business. He even succeeds with a proposal to have TJ’s outlets opened in district courts.

Finally, the day comes for Gupta to retire from prison life. Nothing can shock him any longer; equally, all notions of jail being a space where convicts may be reformed have vanished.

“I was just a weary man doing the job that he was assigned to do,” he says. But it is in telling the story of his time at Tihar that he may have performed his most valuable service. “I thought it was time to let the world know the reality of our prison system,” he says, “so that someone can fix it.”