Elisabeth Åsbrink's 1947 begins appropriately, in January. At the start of that year in the Palestinian village of Arab al-Zubayd, a 16-year-old girl is one of several children captivated by an itinerant entertainer's tales and magic box pictures.

In the White House, President Harry S Truman writes in his diary and thinks about his predecessors, some of whom are “controlling heaven and governing hell”.

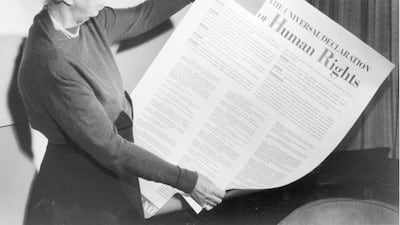

In New York, Eleanor Roosevelt convenes the first meeting of the first session of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. Thousands of Nazi fugitives stream into Denmark and Sweden, and then escape to South America.

The Communists win a landslide victory in Poland’s elections. And in a rural town outside Cairo, a clockmaker’s son yearns to “turn time towards Islam”.

At the end of the book, and by the end of the year, the world has changed dramatically. The Cold War has heated up and Truman has created the CIA. Nazis continue to flee Europe but so too do Jews in search of their promised land.

The clockmaker’s son, Hasan al-Banna, has instructed his Muslim Brotherhood to prepare for jihad. Over the coming months the UN General Assembly will recognise genocide as an international crime, and the Palestinian village will be razed. The man with the magic box will not be back, Åsbrink explains: “there is nothing to come back to”.

The book's subtitle is When Now Begins. Åsbrink – a journalist and author from Sweden – posits the argument that 1947 was not just a turbulent year to file and forget but a pivotal year marked by critical turning points which have shaped, or disfigured, our modern world.

Rather than cleave to convention and divide the book into chapters relating to specific upheavals – social, cultural, political, economic – Åsbrink has taken the original approach of proceeding through the year month by month and covering all areas in short, concise sections.

_____________________

Read more:

Book review: A tale of the loneliness of the hunted in The Tiger and the Acrobat

Book review: Daniel Ellsberg discusses loose links in the US nuclear chain of command

Book review: Nicola Pugliese's Malacqua reflects the political unrest of the time

_____________________

The sections come with a geographical heading and range from two-line summaries to eight-page reports; condensed vignettes to fact-filled episodes. This snapshot-type structure, together with the lively, lyrical and consistently fascinating content, makes for a unique history lesson.

Åsbrink’s main strands are not passing events but unfolding crises, whose developments and ramifications she monitors on a monthly basis. Most of them concern the rise and fall of nations and the clash between East and West. A UN committee is tasked with finding a solution to the problem of Palestine in four months.

A British lawyer is given five weeks – “no more, no less” – to draw borders separating India from Pakistan. The exploits of Swedish Fascist Per Engdahl and those of his other European counterparts are indicative of a resurgence in the Far Right (“a pendulum about to strike back”). And piece by piece, the mighty edifice of the British Empire starts to crumble.

Åsbrink impresses with her astute portrayal of post-war uncertainty and confusion, and her searing depiction of violence and mayhem – in particular the bloodbath of Partition and massacres in Palestine.

But her book doesn't only follow attempts to divide and misrule, or cases of political ignorance and expedience. Åsbrink also tracks a number of significant steps and stages: the first computer bug is discovered, and production begins on the Kalashnikov; at his Paris "dream factory" Christian Dior creates the New Look, while on the Scottish isle of Jura, George Orwell works non-stop – "chain-writing, chain-smoking, chain-coughing" – on his masterpiece Nineteen Eighty-Four. Åsbrink shows world history as it happened seventy years ago, and history in the making.

In addition to this, she blends in personal history. Her middle section, an interlude of sorts stretching out between June and July, is titled Days and Death. "A time without mercy, without words," she writes. Fortunately she finds the right words to sketch the lives and fates of her Hungarian grandparents.

"What else is there to do, other than to describe the world so it becomes visible?" With that visibility comes clarity, for it is here that we realise, belatedly, that one of the figures in Åsbrink's main, calendrical narrative, a 10-year-old orphan and refugee looking for a home, is none other than her future father. This personal touch is a master stroke, as it injects necessary poignancy to a history which, with its distance and its cruelty, can be numbing.

Other inclusions aren’t so effective. Simone de Beauvoir’s romantic affair in New York and anguished longing from Paris is spaced out in tedious soap-opera instalments; hardly a momentous occurrence in the great scheme of things. And many of the recurring references to time are either obvious truths (time “cannot be reversed”) or metaphysical nonsense (“Moving clocks run more slowly than clocks at rest”).

There are notable omissions, too. For a book that measures the long shadows cast by the war and the Holocaust, it is odd that Åsbrink makes no mention of one key 1947 publication, Anne Frank's The Diary of a Young Girl. And yet for the most part Åsbrink's chronicle contains all the right ingredients, along with one or two surprises. Whether recounting the biggest murder trial of the century, revolutions in jazz or a spate of UFO sightings, her prose has vitality and pockets of great beauty: "The memories trickle down through the generations. Stalactites of absence."

No didactic or moralising voice creeps in to force false feelings or strained connections on us. Instead Åsbrink works with great subtlety, allowing us to make our own judgments and trace any parallels or echoes with the present. Fiona Graham deserves credit for her remarkable translation.

Åsbrink gives the last word to William Faulkner: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” It has become something of a rent-a-quote, a go-to epigraph for many an author who delves into history. Here, though, it seems especially fitting. In 1947, Åsbrink notes, the world was rebuilding itself “upon the quagmire of oblivion”.

Her fine book demonstrates how despite paving the way for the future, we are still repeating the mistakes of the past.