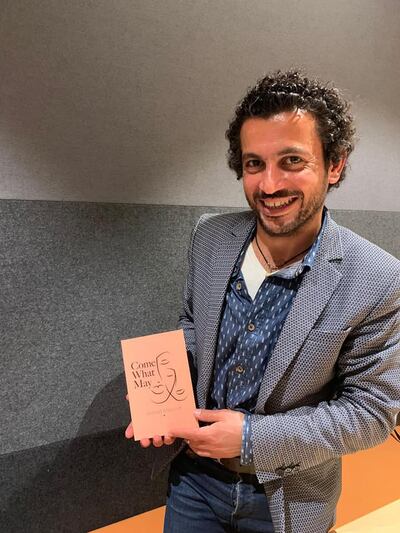

War and survival have long been major concerns in the Gaza Strip, so how does one investigate a murder in the middle of constant conflict? That’s the overarching question asked by Palestinian writer and director Ahmed Masoud in his gripping new novel, Come What May.

Told primarily through the eyes of a 35-year-old widow, Zahra, the story details her desperate attempts to find out who killed her husband in 2014 after he is written off as one of the 2,000 causalities of the Israeli war on Gaza.

While it is ostensibly an intriguing murder-mystery tale, it is also a book about love, betrayal and class issues in a conservative society effectively isolated from the rest of the world.

Masoud, whose first novel Vanished: The Mysterious Disappearance of Mustafa Ouda won the Muslim Writers Award ― also a tale of suspense and intrigue ― tells The National that the genre is “less about the murder and more about the social practice and circumstances in which a crime is committed”.

“The murder is done by a character who has a relationship with multiple characters. This provides me with the ability to bring the readers closer to the humanity of Palestinian people beyond the news headline,” he says.

“I wanted to say to the world that we are like any normal society, we have the good and the bad, the hero and villain. Our social fabric is the same as any society in the world. This works particularly for Gaza which is often represented as a group of terrorist masked men rather than a beautiful society that is deeply rooted to the land and history.”

The compelling storytelling device reels readers in before taking them on an intimate journey of real life for ordinary people living in the besieged enclave.

“I would like readers to feel that they are in Gaza, I want them to learn the names of streets, cafes, restaurants, roundabouts, squares. I also want them to smell Gaza through the food described, the salty and citrus air. I also want readers to learn about the old civilisation and history of Gaza and Palestine and how educated the society is,” says Masoud.

From food and football to passion and patriarchy, Come What May shows how the citizens of an embattled city live while overcoming myriad obstacles.

Based in London, the full-time academic and writer moved to the UK in 2002 from the Gaza Strip, where he was born and raised, to complete his postgraduate degree in English literature.

While completing his doctorate, Masoud founded Al Zaytouna Dance Theatre, for whom he has written and directed several productions for London stages as well as international ones.

As well as numerous academic articles, Masoud has written and directed several plays, including The Shroud Maker, Camouflage, Walaa, Loyalty, Go to Gaza, Drink the Sea and Escape from Gaza.

It’s clear that Gaza, a territory that has been under a land, air and sea blockade for nearly two decades, is a major inspiration for the novelist, but in Come What May Masoud skilfully weaves many important and often less-discussed issues of everyday life in the Mediterranean territory into the tapestry of his novel.

In a predominantly patriarchal society, Zahra’s defiant decision to live alone and pursue her husband’s killers against her family’s wishes is a critique of the wider social issue of gender equality.

Masoud says he tapped into the experiences of his five sisters, who helped him examine and flesh out some of the difficult issues he covers in the novel.

The writer says he was trying to shed light on other problems in his society.

“The occupation is a big problem of course, but so is misogyny, and women in Gaza often just want to be able to live and work in peace and are less concerned with the war and occupation than they are with their personal freedom,” Masoud says.

Humour is a trait Masoud says his countrymen often turn to as a way of dealing with their tragic circumstances and he sprinkles it throughout the book. When Zahra asks her brother why, during the 2014 war, he is more concerned with watching football than the news, Masoud writes: “His response was that war came every two years in Gaza but the World Cup came only every four years.”

Masoud’s descriptions of the smells and tastes of local dishes throughout the novel builds on the rich fabric of Gaza created in his book.

It was a purposeful topic, he said, because of how “integral food is to Palestinian culture”. He says Gazans’ particular predilection for spice means “you really have to have a strong stomach”.

Fear, Masoud says, is as pervasive a concern in Gaza, as is food, with the two inextricably linked, particularly for refugees like himself.

Growing up in Jabaliya camp, the largest of the Gaza Strip's eight refugee camps, Masoud says his family, like others, were always concerned about the availability of food. He addresses the issue by describing the weekly queues for UN food packages containing staples such as rice, oil and corn beef — “which I hated”.

Class issues and intra-Palestinian prejudices, particularly between long-time residents of Gaza and those who fled to the territory after the Arab-Israeli war in 1948, are also running themes in the novel.

Masoud says he was drawing attention to internal social dynamics in Gazan society that many outside would not necessarily be aware of.

He said he became conscious of these differences when he left Jabaliya camp to study English literature at university in Gaza — like his main character Zahra — and experienced a certain condescending attitude from the urban population.

It is this exploration and unearthing of so many disparate yet interconnected sociopolitical issues in Gaza that is the book’s real triumph.

For a territory that has for years been synonymous with death and destruction, discovering the more nuanced and intimate parts of it is the real treasure of Come What May.