From the 1950s, significant changes swept through the Arab world – the disintegration of colonial powers, industrialisation, war and the mass exodus of people. In this period until the 1980s, various modes of abstract art also began to spring up in the region.

The artistic movements produced in these decades is the focus of the exhibition Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s to 1980s, which opens on January 14, 2020 at New York University's Grey Art Gallery in Manhattan.

The show will feature nearly 90 works – paintings, sculptures and works on paper – all drawn from the collection of the Barjeel Art Foundation in Sharjah, and will present a diverse list of artists such as Ahmed Cherkaoui, Huguette Caland, Hassan Sharif, Etel Adnan, Samia Halaby, Mohamed Melehi, Saloua Raouda Choucair, Dia Azzawi and Kamal Boullata.

At its core, the exhibition not only seeks to trace artistic developments within the Arab world, but to challenge the framework in which art history is developed, particularly when it comes to global modernism. It raises important questions about how to study abstract art across different geographies and what tools are in place to analyse these movements.

"The work of artists featured in the exhibition not only expanded the vocabulary of abstraction, but also complicated genealogies of origin, altering how we understand the history of non-objective modern art at large," says Suheyla Takesh, co-curator of the show and at the Barjeel Art Foundation. "More than tying the works into a single history, Taking Shape seeks to contribute to the conversation on the global genealogies of abstraction, and grapple with methodological challenges of studying abstraction in non-Western contexts."

According to Takesh, the exhibition will be laid out in "loose categories" in order to create an "open-ended" narrative. One of the most significant movements in modern Arab art highlighted in the show is hurufiyya, also known as "letterism", which was defined by its departure from classical Islamic calligraphy. While calligraphy was outlined in precise styles, hurufiyya stripped letters down to their visual elements. The resulting works focused on individual expression that was influenced by the artists' experiences. The pioneer of the movement was Madiha Umar, an Iraqi artist who dissected curves and shapes from Arabic letters and used them to create new non-figurative forms.

Palestinian artist Kamal Boullata, who died in August this year, approached the written word differently, inserting Kufic script into his vibrant geometric canvasses. In the 1960s and 1970s, Sudanese painter Ibrahim El-Salahi and Egyptian Omar El-Nagdi sought to retain the spiritual elements of script and use abstracted letterforms to express religious ideas.

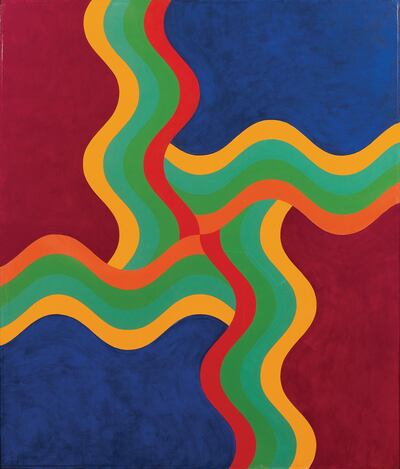

Other artists looked to geometry and mathematics as a way to inform their non-figurative works, including Lebanese artist Saloua Raouda Choucair who erased obvious references to specific language or objects in her compositions and sculptures. There is also the work of Samia Halaby, who infused Islamic architecture and geometric abstraction while playing with depth and colour.

Also on view are the more political overtures of The Casablanca School, which aimed to decolonise culture and create a visual language more tied to its North African roots rather than Western traditions. This meant the assimilation of traditional material and crafts into art, as seen in the works of Mohamed Melehi, Farid Belkahia, Mohammed Khada and Mohamed Chebaa.

As proven by these artists, the development of abstraction cannot be traced to one point in history or geography. Takesh points out, for example, that seminal artists such as Theo van Doesburg, Max Bill, Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich and Naum Gabo incorporated forms and elements from Africa, Asia and Oceania into abstraction, something that art history can sometimes overlook. "It is hardly surprising that several distinct genealogies of abstraction can be identified if one looks directly at pre-modern artistic traditions from Africa, South Asia, the Far East and the so-called Islamic world," she says.

With shows scheduled across five US academic institutions from January 2020 until September 2021, Taking Shape promises to challenge and broaden visitors' ideas about origins and influences of abstract art, particularly in the Western context. "This is why it is important for the exhibition to be seen internationally, and it is great that we have an opportunity to take it to university museums in particular, where it can be used as a teaching tool," explains Takesh. After New York University, the show will travel to Northwestern University, Cornell University, Boston College and the University of Michigan.

Three years in the making, the exhibition has a corresponding catalogue with nine essays from Takesh, Lynn Gumpert, the director of Grey Art Gallery, Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, founder of the Barjeel Art Foundation, and academics such as Salwa Mikdadi, Nada Shabout and Iftikhar Dadi.