If ever a show could be described as the matryoshka dolls of exhibitions, it's this one. Inspired by the East: How the Islamic World Influenced Western Art is several shows nestled inside one another, some promising, some frustrating. It has been billed as the British Museum's first look at Orientalism, the 19th-century movement in which western painters romantically depicted the Ottoman Empire. But it's done in an ingenious way: the show is a partnership between the British Museum and the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur, where the show will travel to after its appearance in London.

The IAMM has a substantial collection of Orientalism, part of a general rehabilitation of the genre among Middle Eastern and Islamic collectors, who value the works for the aesthetic beauty and record of the Ottoman world, despite the inaccuracies and cliches they often contain. This show pairs Orientalist paintings (mostly from the IAMM) with the items of material culture depicted within them (mostly from the British Museum collection). Thus, a painting of a guard against a background of intricate tiles and mosaic work by Spanish Orientalist Antonio Maria Fabres y Costa, is displayed alongside examples of the tiles seen in the painting (these, from Toledo, are from the IAMM collection). Throughout the show the patterned vases, ewers and mother-of-pearl-inlaid boxes that populate the Orientalist paintings cheerfully pop out of the paintings' imagined worlds and into reality.

These often richly patterned, colourful works show how Eastern influence on western art extends beyond painting, spreading to craft, design and architecture over a long period of time. This rich history of interchange is a laudable goal for a show, but the examples here reach that sticky territory of being both too few and too many. The cultural exchange between East and West scarcely needs to be proven, but if it does, it needs a much larger exhibition than this one.

Where the show soars, however, is in the nitty-gritty details of how exactly the West was inspired. The curators, Julia Tugwell and Olivia Threlkeld, use the combination of material items and representations to show the iterative quality of influence, in which objects from the Middle East, brought to Europe via tourism, trade or colonialism, were used in impressionistic paintings of the region, which were later taken as fact by Europeans, or used to create Arab-like motifs of their own.

Tugwell explains the Alhambra palace in Granada, for instance – the Andalusian marvel built by Spanish Muslim emirs in the 13th and 14th centuries – fell into disrepair by the 18th century. To rehabilitate the building, Spain's government created intricate 2D and 3D models to assist architects in plotting out repairs.

"In turn, these models became tourist souvenirs," she says. "They moved into other parts of Europe, where they would also serve as models of architecture for students who didn't have the means to travel to the Alhambra palace. They became ways of disseminating information and inspiration."

The Spanish model the British Museum shows is extraordinary, beautifully detailed and almost two metres in height, a substantial objet d'art. Two panel doors of a cabinet open to show the Moorish arches, Arabic inscriptions and patterns of the palace in miniature. What a surprise the cabinet must have held for those opening it for the first time.

Fashion was another area through which Middle Eastern inspiration travelled. The 19th century gave rise to a craze for what was called the Alhambra vase, inspired by the kinds of vases used there, which consisted of a large, richly patterned vessel set within a wooden stand of three pincer-like legs.

These vessels showed up in the paintings of the Orientalists. An Alhambra vase appears in Rudolf Ernst's painting of two women shaded from the Mediterranean sun, in the The Wool Spinners, on show in London. European painters used their souvenirs to recreate scenes in their studios after returning from the Mena region and passed them on to others who painted pictures of the region without having been there at all.

“Props were important ways for artists to be inspired,” says Tugwell. “Even if they did not go abroad, they could still add in the props to accurately depict them in the painting.”

The use of props also helps explain the frequent mistakes of Orientalism. These were artists painting from memory and tourist trinkets, as well as from the depictions they saw elsewhere that had been created by others. When Flemish artist Jean-Baptiste Vanmour was given permission in the 1720s to paint a dinner given by the grand vizier in Topkapi, his work became a template for other depictions of the Turkish palace.

"Vanmour was one of the few painters who gained access to the Ottoman court," Tugwell says. "The court had strict ceremonies in which they received ambassadors – they would be taken through the court, given food and received by the sultan. Vanmour depicted the imagery and then, because it wasn't usual for artists to have access, other painters would reproduce the scenes – they would perhaps remove the French ambassador and put in another ambassador – but the Ottoman ceremony had such strict rules it didn't really matter."

Another argument of the exhibition is to frame the interest between East and West as mutual, though it feels as though this is missing context. Inspiration might have been mutual, but it wasn't equally realised – there wasn't a Middle Eastern movement like Orientalism, in which Ottoman artists depicted stock European scenes. When Arab artists travelled abroad during the same period as Orientalism, their landscape paintings were invariably described as Arab regional artists "learning" from the West – a characterisation that bears out the power imbalance and history of colonialism hidden in "inspiration".

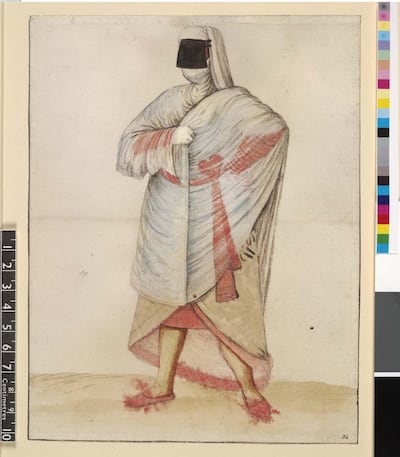

These quibbles aside, Tugwell and Threlkeld's inclusion of early examples of exchange are illuminating: they show a Safavid book from the 1600s that depicts western dress – a man in black felt hat (shorthand for a European), with a face drawn in unmistakably Persian miniature style. The focus on Eastern art production is carried into the 21st century in a section called Disorient, in which four women regional artists – Inci Eviner, Lalla Essaydi, Raeda Saadeh and Shirin Neshat – look back at the viewer, challenging, as Tugwell says, the white male Orientalist gaze.

Enormous territory is covered in this richly packed and ambitious exhibition. You have to hope all that is promised comes to fruition – but in the meantime, visitors can admire the show's workaday details most, such as the stories of poor memory, flights of imagination, recklessness and curiosity that have characterised the long and complicated relationship between West and East.

Inspired by the East is at the British Museum in London until January 26. More information is available at www.britishmuseum.org