“I not only shared my studio with Ismail, but everything,” says Tamam El-Akhal of her life with fellow artist and husband Ismail Shammout. The pair met at art school in Cairo after being driven out of their homes in Palestine in 1948: El-Akhal from Haifa and Shammout from Lydda. Famously, Shammout walked all the way to Jordan, aged only 18.

El-Akhal and Shammout were pillars of the first generation of Palestinian art. As part of the PLO they created posters that acted as calls to arms in Palestine, and organised exhibitions that helped communicate the Palestinian reality to an international audience.

“Before we got married, he asked me how I would feel if ‘we become two wings of the same bird and call it Palestine’,” recalls El-Akhal, who is still producing art in Jordan. Shammout died in 2006 but she still mostly uses “we” to talk about her life. “We could fly across the world to show what truly happened as opposed to the common belief that Palestinians have sold their lands and fled their land.”

Their work is the subject of an illuminating exhibition at the Sharjah Art Museum, as part of its "Lasting Impressions" series of overlooked Arab artists. It starts with the pair's paintings of the 1950s to their engaged work with the Palestinian Liberation Organisation – the high point of the show – to work they produced on the Palestinian struggle in the 1990s and 2000s, including Shammout's Exodus of the Palestinian People. (The exhibition unfortunately could not bring in any panels from his Exodus and Odyssey, which is similar to the latter in style.) It's a chance to see the beginnings of modern Palestinian art – and also to see the work of El-Akhal, who, in a dynamic depressingly familiar, has never enjoyed the same recognition as her husband.

El-Akhal puts this down to this to biases that existed in the Arab world at the time, and which arguably are changing now.

_____________

Read more:

Artist Hazem Harb's excavation of the Palestinian past

‘Solidarity’ and what it means in Palestine’s art scene

Art under occupation: Qalandiya International opens in Ramallah and Jerusalem

_____________

“Unfortunately, in the Arab world, they exaggerate when they say that ‘he is a man and she is a woman’,” she recalls. “When I participate in exhibitions abroad, the foreigners advertise me and Ismail separately. This is when I feel that I am at the same level as Ismail. Whereas when I paint a powerful and meaningful piece of art, the Arab press credit Ismail by listing his name in the Arabic newspapers because they do not believe that the painting was produced by a woman.” She laughs. “They turn a blind eye to the signature.”

The curator, Alya Mohamed Al Mulla, rectifies this, producing a show balanced between the two of them that becomes neither about gender nor even about Palestine, but a narrative of two artists whose work intersected and influenced each other over the course of fifty years.

Early work

The exhibition begins with the work painted while the pair were living in Cairo: portraits and still-lifes with traditional Arab foodstuffs made in an academic, European style. Even at this stage they were well-known; Gamal Abdel Nasser, for instance, personally opened a show of Shammout's work. In 1965, the style and subject matter abruptly shift. The pair joined the PLO, which had been established the year before, and they began making work, in posters and paintings, as part of the Palestinian struggle. Where El-Akhal painted Unemployment in 1956 personified by a figure seated on a wooden chair, head slumped, in 1965 the female figure of Shammout's PLO is a proud mother, head erect, white scarf crisply angled, as she protects her children in her embrace and confronts her unseen enemy.

This was a crucial period of Palestinian work. In those years El-Akhal and Shammout, in addition to contemporaries such as Mustafa al-Hallaj and Abdul Hay Mosallam Zarara, helped create the iconography of the Palestinian cause that still circulates visually: the mother as a cipher for Palestine, environmental details such as orange groves or olive trees, or traditional clothing such as embroidered dresses or the checked keffiyeh. The PLO artists helped turn these motifs into symbolically charged emblems – a shorthand for Palestinian self-sufficiency and identity.

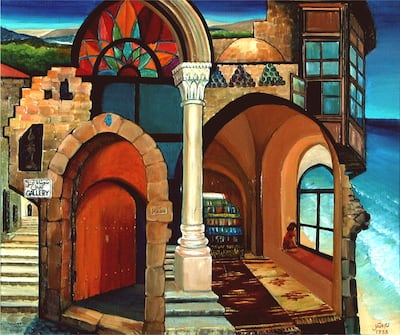

Artists were also involved at an organisational level. Shammout was director of the arts section of the PLO and later Secretary General of the Union of Palestinian Artists. He and El-Akhal contributed to the frequent exhibitions abroad that were organised by the PLO among its allies. Several of these shows have become iconic, in part because their contents have been lost. Documentation, and some of the works themselves, from the International Exhibition for Palestine in 1978 were destroyed during an air strike on the PLO office during the 1982 Israeli invasion of Beirut. Works from an exhibition that Shammout organized in Beirut at the Karama Gallery were also lost in the same conflict.

El-Akhal underlines that despite their shared subject, their presentations differed: “We both reflect in our paintings the plight of our people, which both Arabs and foreigners are able to read and interpret. But each one of us would paint it differently.”

“We both used the same studio to produce our works of art but each one of us occupied a space in a different corner,” she continues. They used to play the same music, though she adds that at times she would pop on headphones to listen to Oum Koulthoum or Mohamad Abdel Wahhab.

But what seems most striking about their work is less the difference between their works, but the sheer amount of variation within both of their practices. Shammout, for example, wends from the expressive Boy on a Rope, of a young child tightrope-walking against a painterly blue background, to the surpassingly powerful, more folkloric portrait of 1970, of a white-scarved woman staring determinedly forward. El-Akhal likewise switches register from portraits to crowd scenes to landscapes, each subject given a different treatment at times. She has an extraordinary appreciation for the dignity of labour, as in two scenes of "samed" (or resistance) workshops in the 1970s: detailed illustrations of people deep in concentration.

1982: Israel invades Lebanon

Their work shifted again in 1982, when the PLO leadership and exiled Palestinian art community dispersed after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon. The pair themselves left Beirut two years later, resettling in Kuwait. Their work turned away from immediate depictions of Palestinian struggle: Shammout painted beachscapes with fishing boats and El-Akhal the interiors of houses, but the spectre of Palestine remained. Martyred families sit on the doorsteps of houses; in another painting, a young boy struggles to hold up the limp, lifeless body of a nude man, draped over his shoulder. Around this time, she also started to include the motif of a white horse, which she says came as a response to the massacres of Sabra and Chatilla in 1982.

“I wondered, ‘where are the Arabs?’”, she recalls. “No one reacted and there were no demonstrations. I was very frustrated. I happened to read a book at that time about a white horse [that] describes a thirsty horse refusing to kneel down and drink the water he was served. It confirmed the saying ‘We will die in a standing position and refuse to kneel down and surrender’.”

This is an exhibition of historical value, and part of the joy of seeing it in the Sharjah Art Museum context is – paradoxically – to lift the pair from the historical role they played. Particularly because early Palestinian art was so closely wedded to its end goals, there is a difficulty in appreciating it beyond the part it played in the Palestinian struggle. This is also reinforced by the fact that many of the images of Palestine become similar after a time: heroic villagers and anguished survivors are moving, but not in repetition. The museum's organisation of this show, in rooms off a ramped corridor, adds to a feeling of dogged chronology; it would be nice to vary the engagement with the works a bit, but the museum setting overall enlivens this work. El-Akhal's motif of the horse, for example, connects heartbreakingly to the Iraqi artist Kadhim Hayder's Fatigued Ten Horses Converse with Nothing (The Martyr's Epic), of grief and mourning during the violence in Iraq after the Baathist coup in 1963, which is on view in the museum's Barjeel rooms. Shammout's and El-Akhal's commitment was to Palestine, but this exhibition helps broaden the reach of their contributions.