The moment you walk into Edvard Munch: Landscapes of the Soul, there it is: The Scream. Or, at least, one of only a handful of lithographs of the 1893 masterpiece (the two painted versions rarely leave Norway).

The effect of being greeted by Munch's most famous work – that haunted figure, hands over its ears, wailing in despair on behalf of all of us – is twofold. Firstly, it makes it clear that the show at the King Abdulaziz Centre for World Culture (Ithra) in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, the first dedicated to Munch in the Middle East, means business. If The Scream is here, it's safe to say the curators aren't mucking about. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, encountering The Scream this early on allows you to enjoy the rest of the exhibition – and there is so much to enjoy here – without that nagging voice in your head whispering, 'OK, great, but where's the really famous one?' It's a privilege to see The Scream and a relief to leave it behind.

What follows is an extraordinary selection of works – 40 in total – from different stages of the Norwegian Expressionist's life (1863-1944). Landscapes of the Soul, a collaboration between Ithra and the Munch Museum in Oslo, is split up into five pavilions, dotted around the Great Hall.

The show is not chronological. Instead, each pavilion explores a different emotion in Munch's work, spanning 60 years: melancholy, love, despair and loneliness (the first pavilion, which houses The Scream, alongside two self-portraits, is titled "Landscapes of the Soul").

These titles are not especially precise, since you'll find plenty of despair in the pavilion called "Love" and no little melancholy in "Loneliness". The human mind is better thought of as a Venn diagram of feelings. But these labels do at least force us to consider Munch's works in a psychological context; to see his paintings and drawings as allusive even when they appear to be defiantly representative. As Munch, one of the forerunners of Modernism, once said, "I don't paint what I see – but what I saw." The landscape – the outer – reflects the inner (the title of the show rams this point home).

So when confronted with New Snow (1900-1901), for example, are we looking at a beautiful winter scene of pines sagging under great dabs of powdery snow? Or a path leading to nowhere beneath a slate-grey sky, painted by an artist who would suffer a mental breakdown in Copenhagen just a few years later?

Similarly, we might initially associate the fizzing oranges and shocking yellows of The Women on the Bridge (1934-1940) with feelings of joy, but look a little closer and what we see is a huddle of women blocking out the attentions of several forlorn men. By hanging this painting in "Despair", the curators are pushing us to interrogate and challenge the stories our eyes are telling us. "Munch didn't want specific interpretation of his work," says Stein Henrichsen, director of the Munch Museum. "He just wanted people to meet the artworks and to reflect on the content … You have to experience Munch on an emotional level."

Much of this will no doubt be familiar – some 28,000 articles are written about Munch each year – but for many visitors to Landscapes of the Soul, this will be their first encounter with the artist. It is important to assess the exhibition in this context. It serves as an excellent introduction or primer, which spans decades and styles, rather than any specific aspect of Munch's work. "We just wanted to show a little bit about how Munch was thinking," says Henrichsen. "How he changed art and what made him special."

You emerge from Landscapes of the Soul with a strong grasp of Munch's biography, too, and how it affected his work. At the age of five, Munch lost his mother to tuberculosis and, nine years later, his sister succumbed to the same disease. One of the highlights of the show is the pairing of The Sick Child I (1896) with The Sick Child (1927). The rough early version, the young girl's ghostly face framed by a cascade of red hair, hangs opposite a bolder rendering, painted three decades later. This version is richer and fuller, a shadow come to life.

Munch left Norway in 1889, while still in his twenties, and travelled to Paris, where he began to focus on making art that reflected his – and our – inner turmoil. During this period, he produced Moonlight. Night in Saint-Cloud (1895), a bleak etching, scratched in shades of grey, of a man sitting by a window engulfed by darkness. The whole room appears to represent the man's blackened thought clouds.

Munch then travelled around Europe for a number of years, exhibiting his work in Dresden, Kristiania (later to be renamed Oslo), Paris and Vienna. He suffered a mental breakdown in 1908 and the nature of his work changed hereafter. Munch spent more time at Ekely, his country retreat on the outskirts of Oslo, and more colour appeared on his canvases.

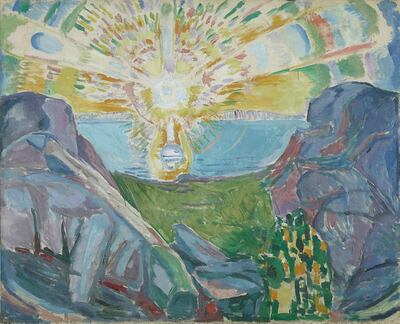

The works from this period are some of the most invigorating in Landscapes of the Soul. Ripe, red fruit weighs down the branches in Apple Tree by the Studio (1920). Standing in front of The Sun (1910-1913), meanwhile, you can almost feel the warmth on your cheek, as golden rays filter between two rocks, like light barging through a crack in the curtains. Here, then, is Munch the optimist.

It is ambitious to try and give an overview of Munch's career in just 40 works and inevitably there are gaps here. There's no mention, for example, of Munch's works expressing contempt for the First World War. Added to this, the lack of chronology means the show can feel scattershot. Self-portrait After the Spanish Flu (1919) hangs alongside Starry Night (1922-1924), Munch's wonderful, spooky painting of the night-time view from his veranda at Ekely. But why exactly, other than a general nod towards Munch's preoccupation with death?

For all this, however, Landscapes of the Soul overwhelmingly achieves what it sets out to do, which is introduce Edvard Munch to a new audience, to showcase his vibrant palette, to explore his biography and to investigate his anguish and his joy. In short, to illustrate that there is more to Munch than The Scream.

Edvard Munch: Landscapes of the Soul is on show at the King Abdulaziz Centre for World Culture (Ithra) in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, until September 3. For more, visit www.ithra.com