Manal AlDowayan is on her way from the desert regions in the north of Saudi Arabia to Jeddah when we speak. She's splitting her time between two new major commissions, both ambitious in scale and concept. Not bad for someone for whom art was not a first career.

In the arid landscape near the city of Al Ula, home to the kingdom's first Unesco World Heritage Site, the Saudi artist is making what she describes as "puddles", a land art installation, entitled Now You See Me, Now You Don't, intended to draw attention to water scarcity. "Puddles are humble, beautiful things, and they used to have a longer life on Earth," she says. "Al Ula was founded because it had plentiful springs, it was this oasis in the desert, but as the climate changed these local communities had to start tapping into the underground reserves, so even when it does rain, puddles disappear almost instantly."

Saudi Arabia, despite its economic influence, is one of the poorest nations in terms of natural renewable water resources. A 2016 statement from King Faisal University suggested the kingdom only had enough groundwater reserves to last another 13 years, and while the government is now promoting water-saving initiatives, AlDowayan says the problem remains urgent.

It is a serious issue the artist is addressing, but she has done so in a fun fashion. AlDowayan has installed a series of 12 trampolines flush to the dusty ground, some more than four metres in diameter, but invisible as the visitor enters the sun-drenched valley. "I wanted kids to engage, as they might jump in a puddle. At night the work is up-lit and appears as strange black pools. People are nervous at first, but I've seen young and old now have a go."

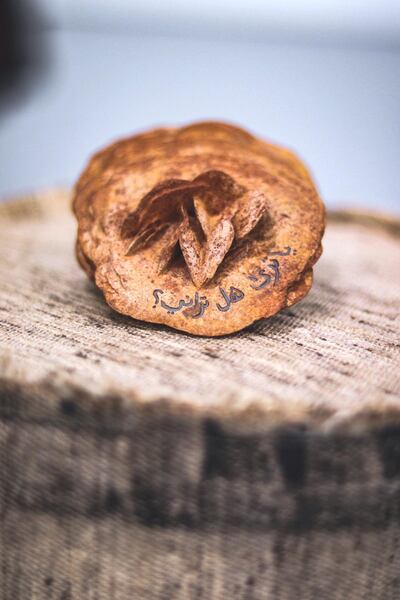

This latest project is part of Desert X, a sculpture biennial that originated in the US, but for its third iteration was invited to Al Ula by the Saudi government. In Jeddah, AlDowayan is exhibiting at the annual 21,39 Jeddah Arts, where she will show a work in which the desert is again a concern, represented through a large textile sculpture featuring the motif of the desert rose, the rosette formations of gypsum that occur naturally in water-starved landscapes. The artist regards it as a powerful symbol, one which, in part, has some autobiographical reference. "I was surrounded by geologists as a child, as such I look at landscape in a particular way. The desert rose I think of as a witness that comes and goes. We don't have many flowers in Saudi, so this is the closest it comes." It is a typical statement from AlDowayan on her art. Poetic, but for all the lyricism, underpinned by a steely political and social point. "I work in a lot of different media, my projects always take different forms, and have different politics, but ideas of disappearance and invisibility run through everything I do."

Humble beginnings and a feminist father

The artist, 46, was raised in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia, in Dhahran, in a semi-enclosed campus run by Aramco, the oil giant for whom her father worked, and at which she, too, would embark on an early career. Art, however, became important to her when was given a camera aged 9. She became obsessed with photographing her family, documenting their holidays and life among the oilmen. She discovered that Aramco ran a photography club and operated its own darkroom that was free for employees and their families to use. It was hard to get photographic material in the kingdom during the 1980s, she says, so when a stock of Kodak rolls did come in she would buy them all. “I think I bought all the photographic material there was in the kingdom at one point. I became a total scavenger for this stuff.”

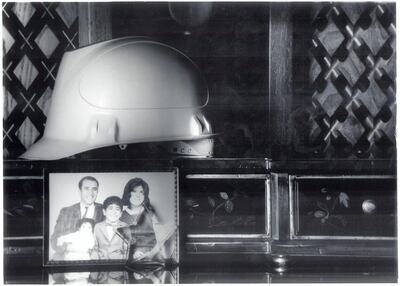

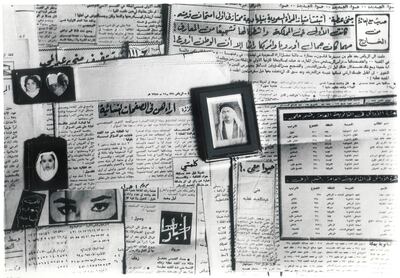

One of her earliest works, from 2012, is a series of black and white photographs that document the men and women who built Saudi Arabia's oil industry. Titled If I Forget You, Don't Forget Me, the pictures feature prosaic objects, which the artist says had sentimental value for the subjects: a hard hat, a paperweight, old fading snapshots in which the pioneers of her parents' generation pose proudly. Moustachioed men with slick side partings who were at the forefront of the kingdom's rapid industrialisation in the 1940s and 1950s. It serves as a moving piece of social history, but it was also a deeply personal project for AlDowayan, as she made it a year after her father, who had lived with Alzheimer's for some time, died.

"I was asking: what does it mean to disappear from memory? There's a power and a weakness within that question. I started looking at the objects my father left behind, objects with no financial value, but that have an emotional aura. That led me to the people who surrounded my family when I was growing up in this incredible community. Oil has its own story, both positive and negative, but it was a pioneer culture in Saudi Arabia, a place where dreams were made. So I went round photographing objects that people attached to. I took the photographs in their retirement offices."

Her father was not particularly happy that she pursued art as a career initially. "He was a feminist. He didn't know he was, but my father said financial independence would empower us." Art, he thought, was a petty dalliance, only taken by the children of the rich. In 1990, AlDowayan went to Boston to study computing and, after a stint at Aramco, to London to earn a master's degree in systems analysis. There, unbeknownst to her family, she used all her spare money to pay for evening classes at the Central Saint Martins art school.

Challenging the West with philosophy from the East

Returning to her oil job in Saudi Arabia, AlDowayan began to moonlight as an artist until, in 2009, she was offered a residency at the Delfina Foundation. This show of support gave her confidence to quit the day job and make art her full-time gig. It was a solid decision, as she has since had several solo exhibitions, including at Alserkal Avenue in Dubai, the Mathaf Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha, the British Museum in London and the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto. Last year she returned to the UK to complete a second master's, this time at the Royal College of Art.

“All my lectures referenced European philosophers, and it was very difficult to have a debate that came from my context. I ended up writing my whole thesis referencing only Arab philosophers. My teachers challenged me with western thinkers, so I challenged them with ideas that come from the Arab world.”

Her work is increasingly being appreciated outside the region. She was commissioned by Sweden's Nobel Museum to produce two sculptures based on literary laureates for a show last year by the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Knowledge Foundation in Dubai, which were displayed at La Mer. One took inspiration from works by Naguib Mahfouz, featuring dozens of orbs in which AlDowayan showed imagery from the many film adaptations of the Egyptian writer's much-loved Cairo Trilogy. "Mahfouz created microcosms in these stories. Through his characters he would talk about the politics of the Arab world, social structures, issues of poverty and wealth." Her second work for the Nobel show was made after having read The Unwomanly Face of War, an oral history of Soviet women in the Second World War by the Belarusian journalist Svetlana Alexievich, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2015. AlDowayan realised that despite this history of women in battle, she had never seen female toy soldiers. Scouring online and going on hobbyist expos drew a blank, so she had a miniature army manufactured and installed in the exhibition.

A comment on women's rights

Her practice, which has incorporated photography, sculpture and large installation, has long focused on the role of women in society. At the Art Basel Miami fair last year she exhibited Watch Before You Fall (2019), for which she printed images of desert roses on textile alongside words reproduced from a religious book instructing women how to behave when going shopping.

As pointed is a piece called Suspended Together, an installation featuring 200 white porcelain doves hanging from the ceiling. It was made in 2011, eight years before the kingdom scrapped a system in which Saudi women needed the consent of a legal male guardian to travel abroad, and on the side of each of these birds the artist had reproduced a different woman's permission-to-travel document.

AlDowayan is adamant, though, that her work does not re-tread western cliches of Saudi Arabian art. Her 2005 portrait series, I Am, featured photographs of women, each titled after their profession. "I am a computer scientist", "I am a scuba diver", "I am a UN officer", and so on. In a satirical allusion to the West's preoccupation with the role of the veil of Saudi society, each woman partially covers her face with a prop relating to her job, be it a keyboard, goggles or passport.

"There is this uniform image of what a woman from Saudi Arabia looks like, with no variety, no individuality," she says. "At the beginning of my career I had to really explain through my work that this is not the case. Even now my art is still received very differently in the East than it is in the West. Art from the West is just art; art from the East is regarded as 'Islamic art' or 'female art' or 'Arab women's art'. Sometimes these categories help people to step into the work, but they also belittle it, reduce its power and that of the creativity that is coming from this region."

The fact projects such as Desert X address global concerns, and not necessarily local political ones, is positive, says AlDowayan. "My work has been written about in western newspapers that are very critical of the politics of my country, but there's an acceptance now that Saudi Arabia is not just about this.

“People do not just take the news from the TV any more, they take it from Twitter, from social media, but I also think they form opinions and receive information through art. I have the opportunity then to smash the single monolithic vision of the region.”