In summer 1924, a highly unusual event took place in Leningrad just outside the city's Winter Palace, the pre-revolutionary home of the Romanovs, the former Russian imperial family.

On an enormous board of squares, which had been painted onto the cobblestones outside the old Winter Palace, Peter Arsenievich Romanovsky and Ilya Rabinovich vied for mastery in a game that took the martial associations of their beloved chess to their logical conclusion.

Playing for five hours in front of a reported crowd of 8,000 spectators, Romanovsky and Rabinovich issued orders via telephone that sent living members of the Red Army and Red Navy across the giant board as they searched for an endgame.

Ever since the invention of the precursor to chess, chaturanga, was invented somewhere in India in what is believed to have been the 6th century, the game has not only featured martial pieces – war elephants, chariots and infantrymen featured in the earliest sets – but it has also been used as a metaphor for warfare and military strategy and tactics.

Those martial associations, and the creeping and quiet militarisation of the games we play and the words and language we use, are the subject of The Line of March, Pouran Jinchi's latest solo show, which receives its world premiere at the Third Line Gallery in Dubai on September 13.

Taking her inspiration directly from several sources including moments such as the Romanovsky vs Rabinovich game as well as the ornate and highly fetishised world of military uniforms, decorations, camouflage and communication systems, The Line of March displays the same complex processes of personal experience and layering that define Jinchi's work regardless of its ostensible subject matter.

After 9/11, Jinchi produced a body of work that engaged with notions of nature and devastation, while around 2004 she began to produce her Aleph series, named after the first letter of Farsi, Arabic and Hebrew alphabets, which celebrated the intrinsic beauty and potential for abstraction in calligraphy and script by focusing on individual letters.

Jinchi's continuing concern with language and communication, minimalism and abstraction is just as evident in The Line of March, which takes its name from a most unlikely source, an early 18th century military painting by the French Rococo painter, Jean-Antoine Watteau.

One of only four paintings that featured in Watteau's Soldiers: Scenes of Military Life in Eighteenth Century France, a small and highly unusual show at the Frick Collection in Manhattan, Watteau's The Line of March, like Jinchi's series, was also made in response to a moment in history defined by global warfare, perpetual conflict, and pervasive militarism.

Rather than featuring what are considered to be Watteau’s speciality, amorous aristocrats and swooning ladies in mythological and theatrical landscapes, the works on display at the Frick Collection were executed between 1709 and 1715 and represented a form of alternative reportage on the War of the Spanish Succession, a devastating European dynastic struggle that eventually spread from Florida, which was controlled by Spain at the time, to Hungary. The war is now considered to be the world’s first global conflict.

Featuring a column of soldiers making their way toward a battle marked only by a flash of gunfire, The Line of March is Watteau's only canvas from the period to depict some sort of recognisable action. Elsewhere, he chose not to report directly from the front but to record the collateral impact of conflict and it is here, in a wider consideration of violence, that the links between Watteau and Jinchi resonate.

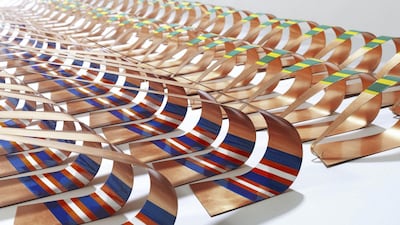

In another historical military reference, a line divides the copper and brass pieces that form Jinchi's minimalist and chess-inspired sculpture, The Red Line (2017). Shaped and decorated with stripes that conform to their own internal hierarchies, the installation not only riffs on the Romanovsky and Rabinovich game but on the institutionalisation of violence in the games we have played for centuries.

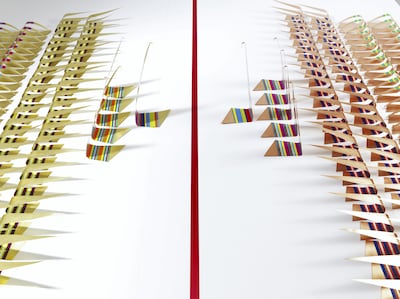

Pieces such as Jinchi's sculpture, J as Juliet (2017), which is covered in different versions of the calligraphic letter J, not only explore the abstract potential of calligraphy but also make reference to the militarised, Nato version of the alphabet that gave us Alpha, Bravo, Tango and Zulu.

Thanks to their bright, enamelled surfaces and brick-like composition, J as Juliet and M as Mike (2017) contain a playfulness that is reminiscent of children's building blocks that obscures the fact that their colourful palette and composition is derived military camouflage, ribbons and insignia. The effect is simultaneously seductive and unnerving.

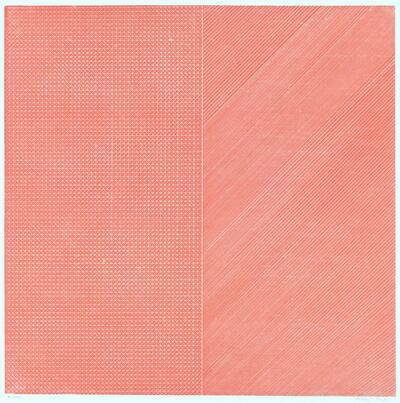

Difficult to discern at first, Jinchi's semaphore-inspired drawings replicate the letters that are represented by individual flags and operate in pairs as a positive and a negative thanks to the way they have been produced using graphite markings on colourfix paper. A form of call and response, they also seem to echo the military practice of radio-based communication in which any statement is always recognised with a negative or an affirmative: "Roger, roger? Copy that."

Jinchi's work has always displayed a highly sensitive and deeply personal response, not just to her environment but to the history of art.

Soon after she graduated from UCLA and the Art Students League of New York in the 1990s, the influence of Salvador Dalí, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns was evident, as were the longer and deeper traditions of Islamic text-based art, hurufiyya, that she had learnt as a practising calligrapher.

As her practice has developed over the years, her sense of abstraction

has been honed and refined and the references have changed: the deep traditions of Persian and Islamic calligraphy will always be there but in the semaphore-based works such as Echo, Golf and Hotel, the artist also seems to be engaging in a dialogue with minimalists such as Agnes Martin.

Simultaneously rigorous and playful, highly personal and yet historically engaged, Pouran Jinchi manages to combine the calligraphic traditions of Islam with the history of warfare and the trajectory of Modernist abstraction without ever being intimidating, which makes The Line of March rather more than an artistic feat of arms.

The Line of March by Pouran Jinchi opens on September 13 and runs

until October 21 at the Third Line, Dubai. For more information, visit

www.thethirdline.com

________________

Read more:

The 2017 Lumen Prize for Digital Arts shortlist announced

Lubaina Himid gets Turner Prize nod

Why I will always remember the Louvre Abu Dhabi I saw first

________________