Since she left the Glasgow School of Art in 2000, British-Palestinian artist Rosalind Nashashibi has made a name for herself as a filmmaker. In 2017, she was nominated for the Turner Prize, she has had major institutional shows and her films are also collected by international museums.

But her studio, accessible through a grey alleyway in north-east London, is now splattered with paint drops. Books on painters such as Pierre Bonnard, Mark Rothko and Paolo Uccello are stacked on her desk. A few years ago, Nashashibi started painting again alongside her film work, and she is now artist-in-residence at Britain's National Gallery.

"I had always been making two-dimensional work, such as prints, collages and photographs, but gradually I was making my way back to painting as a more daily practice," she says. "The first time I gave it a go was when I decided to join my children at the table to paint. With kids, you always have paint and paintbrushes out, and one day, I wanted to make something, too. The decision was quite a serious one for me."

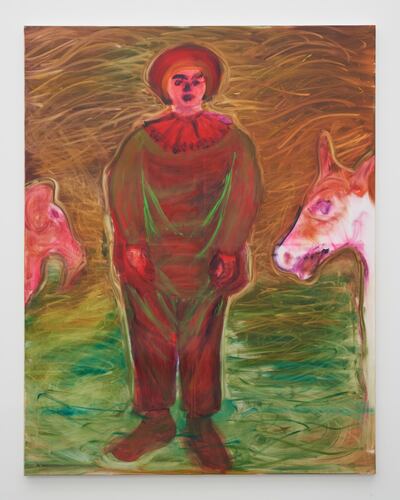

Nashashibi began creating softly edged paintings that drew on artists of the past, men such as Bonnard, Uccello, Paul Gauguin and Jean-Antoine Watteau, whose portraits, particularly of women, Nashashibi subtly displaces. Figures are sheared of their context, while unnatural colours add a feeling of stagecraft to the scenes. In one work in progress, the face of a young woman in a white Breton cap pokes out from the side – taken from a crowd of women in a painting by Gauguin and here given focus.

In another exquisite rendering, Nashashibi has painted the face of Gauguin himself, alluding to a self-portrait exhibited at the National Gallery. The 19th-century French painter's hair and forehead are daubed through with olive-green paint and the same colour is used on his recessed eyes, which gives him an expression of mistrust. He holds a blue-and-white striped frock in front of him, as if snooping.

Nashashibi made it after finishing a film about Gauguin's paintings of Tahitian women. Titled Why Are You Angry? (2017) and made with artist Lucy Skaer, with whom Nashashibi has long collaborated, the film shows how historical impressions of the women of Tahiti have been filtered via Gauguin. "We see the women," she says. "But only through his eyes."

She began her time at the National Gallery last August, though she has yet to take up the "in-residence" part, as the museum's new studio is not yet finished. The National Gallery has revamped its residency programme, giving artists a stipend so they can focus on their work during their time at the gallery. Nashashibi is the first in this new cohort and, a lack of studio space notwithstanding, she enthuses about the access she's had to the museum so far.

Every Monday morning, she meets one of the curators, who takes her on a guided tour of their area of expertise: Northern Renaissance, Dutch Golden Age, Romantic or Impressionist. “It’s been an education,” she says. “Art school in Britain teaches you how to think like an artist. They don’t tell you about a lineage of artists, or teach artists how to position themselves within this lineage.”

Nashashibi was born in the UK to a Northern Irish mother and Palestinian father, who left Jerusalem to study. His family is historically important, holding the ceremonial position of being the custodian of Haram Al Sharif, but Nashashibi says her father never spoke about it.

"For him, that would have been bragging – and perhaps too painful to talk about. I only learnt about it years later, through my aunt [art historian Salwa Mikdadi, who teaches at New York University Abu Dhabi]."

Like many children of the diaspora, Nashashibi treats this distance with a combination of matter-of-factness and regret. She recalls, for example, that early in her career she won an award from the Qattan Foundation in Ramallah. One of the judges, Palestinian artist Kamal Boullata, "spoke about my family in a spiritual way that I could never access".

Palestine has been a recurrent, if not frequent, subject of Nashashibi's work. In 2002, she made the film Dahiet Al Bareed (District of the Post Office), which is about a neighbourhood established by her grandfather, who was the postmaster general under the British and later the Jordanians. The area, in what was Jerusalem at the time, was set up as a utopian community for postal workers.

Nashashibi's film is anti-sentimental and barely nods to these intentions, or her own relationship to it. Instead, it operates as a view on daily life in the present: children playing football, the sound of the adhan in the streets and barbers styling hair.

In a slightly more fantastical style, she made a second work in Palestine in 2014, filming it right before a period of unrest. The work is titled Electrical Gaza and it combines footage of life in the enclave with different suites of music – singing, string instruments, electronic music – to get across, as she says, "the unhealthy, electric" imprisoned feeling of the occupied Palestinian territory.

These films feel different from the paintings she makes now. The film work is rich, soaking in all parts of a scene – a man speaking, a woman walking behind him, the sun setting over a wall's edge. By contrast, her paintings advance their layering by hiding certain parts of the scene, with figures lopped off at the edges, hidden under duvets or lurking behind fancy frocks. Dark red pillars frequently bracket the paintings, as if turning whatever is inside into a stage set.

Nashashibi says she is surprised, however, by the idea of there being a difference between her works. For her, they constitute a spectrum of representations of reality.

"In my films, I try to show how the everyday is a number of dimensions happening at one time," she says after explaining the plot of her latest film, a sci-fi trilogy inspired by American author Ursula Le Guin. "They're about sadness, passion, the drama of the everyday – that's anything but mundane.

"But there is another, internal world that a documentary approach can't reach. The paintings access this world. We experience each event on different levels of reality, qualities of understanding and awareness. It's like when you are standing in water. Your feet are wet, but your legs are exposed to the air."