Sixteen years ago, young Danish-Icelandic artist, Olafur Eliasson, 36, had a knock on his Berlin studio door. His visitor was Nick Serota, director of London’s Tate Modern at the time, with an interesting proposition. “There is this very large space in the museum, and while I know you are a young artist, why don’t you come over and we’ll see what you can do?”, he said.

So Eliasson created an epic installation for the museum's Turbine Hall, which little did he know then, would still be a talking point today. The work, entitled The Weather Project – a half-circle of orange light that turns into a full circle in the mirrored ceiling of the grand entrance hall – became a social phenomenon. It can still be viewed in the space today and remains the museum's most famous commission to date.

Now, at 52, Eliasson returns to the museum with what he emphatically calls a mid-career survey – "there is still lots I will do," he says. The exhibition, In Real Life, brings together projects such as his famous mist-filled installation Your Blind Passenger, a 45-metre-long corridor that plays with the eye's capacity to add colour to monochrome light, as well as the artist's social enterprises, such as a the chandeliers made as part of the green light workshop, a fundraising project that benefited Iraqi and Syrian migrants to Vienna at the peak of the migration crisis in 2012. "These are projects addressing the real-life affairs that the world is facing," says Mark Godfrey, who curated the show with Emma Lewis, both of Tate Modern.

Two centuries ago, Eliasson, who was born in Denmark to Icelandic parents, would have been classed as a Romantic artist: captivated by nature, he tests the capacity of art to approach the sublime, and asks philosophical questions about colour, such as whether everyone perceives the same as each another other.

In a series of works, he abstracts the colour palette of paintings into graded colour wheels – the work of Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich, for example, becomes a smear of blue and greys and greens.

But Eliasson has also brought this set of interests into the expanded field of contemporary art, where they have flourished. Interaction with the viewer is key to his work. As Godfrey notes, “it takes two”. Eliasson wants to not only use visitors to activate the work, but make them aware of their moment of perception, or as he puts it, “seeing yourself sensing”.

Your Blind Passenger, a dense corridor of fog, is lit with monofilament lights, so that one's brain compensates for the colours that are missing. Each person sees something different: some see blue, some see magenta.

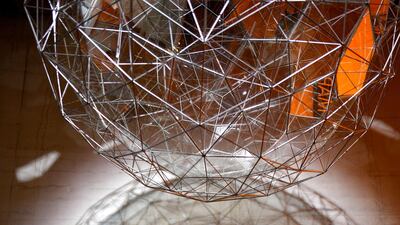

The rounded glass The Seeing Space is Eliasson's nod to the use of orbs in the works of the Old Masters that represented the painting's scene upside down. At Tate Modern, the visitor travels to the other side of the wall to see the upside-down room, with the floor on the ceiling and the viewer's heads floating in the midst of the line of perspective.

In other works, Eliasson recreates natural phenomena, either by simple or complicated technical means, to force a reappraisal of what is already out there. The heart-stopping Big Bang Fountain is a simple water fountain in a pitch-black room where a one-second blast of light illuminates the water as it gushes up and over. The effect is of a series of short glimpses at one of the more extraordinary, fragile and endlessly creative sculptures you might ever see – each disappearing at the moment you try to study it more.

This problem of perception, of trying to hold on to the rainbows, geometric patterns and effects of light that already exist in nature, butts directly against what art tries to do: to hold these ephemera fixed for eternity.

Eliasson wants to have his cake and eat it too, and – not to labour the metaphor – to also live-blog his eating it: unhappy with a Romantic representation of nature, he wants the impact in the gallery, with the viewer made aware both of the magic of nature's improbable existence and the magic of their ability to understand it.

For example when scores of visitors to the Weather Project lay for hours to see themselves reflected in the ceiling, forming shapes with strangers or just chatting in the space – this moment of perception can be awe-inspiring.

It is a complex equation that Eliasson doesn’t always nail, particularly in the realm of works that respond to climate change, which can veer towards the one-liner. If Eliasson is a Romantic artist in a field of expanded artistic possibilities, he also happened to start making work about nature during a time at which nature is most under threat.

"The works' questions are becoming increasingly important as the climate emergency worsens today," he says about the process of returning to his older pieces to put together the show. In one photographic series from 1999, he captured receding glaciers in Iceland, where he spent his summers with his father. He will go back later this year, after two decades, to see how much more they have receded.

His famous Ice Watch brought the climate emergency front and centre: he cut blocks of ice from the Greenland ice sheet and installed them in public plazas in Europe, dramatising the effects of climate change. When it was exhibited in London, outside Tate Modern and the Bloomberg headquarters, it was criticised for the environmental cost of what many saw as a stunt.

Seen as a pure ecological advocacy, the same charge could be levelled at this exhibition, which ignores the larger environmental costs associated with the art world. Eliasson works with the environmental-tracking group Julie’s Bicycle for a few of his works, such as the waterfall he has erected at the back of Tate Modern, in which water spills merrily from what looks like ordinary metal scaffolding.

And he has worked on other sustainability projects, such as a solar-powered torch that he introduced in 2012. But I suspect a younger generation will demand a more holistic appraisal than these works provide.

One final note: if in the days since Eliasson started working in Berlin in the 1990s the climate around him has gone from imperilled into full-blown crisis, then his works track another change as well. Since he started, the world has become a pictorial backdrop for social media – imagine how annoyingly ubiquitous the Weather Project would have been with Instagram. This exhibition, with its fog effects, rainbows and endlessly refracting mirrors feels, already like a Snapchat factory – and Eliasson seems, perhaps surprisingly, in on the action.

Throughout the exhibition, anyone with a question for Eliasson or Studio Olafur Eliasson, his research studio, whether about his work or the state of the world around us, can tweet him with the hashtag #asksoe. He promises to answer one a day, with all questions and answers screened in a video at the exhibition itself.

In Real Life is at Tate Modern until January 5, 2020