A new Instagram collection of vintage photographs is challenging stereotypes of migration between the Gulf and South Asia through intimate family histories. The account is managed by Ayesha Saldanha, a Brit born in India who was inspired by the stories of her own family.

Her grandfather spent nearly all of his working life in Muscat, Oman and Doha, Qatar. Saldanha moved to Bahrain from the UK in 2001 and during 12 years there, she became interested in the connections between the Gulf and South Asia.

The result is Instagram account Gulf South Asia, a gallery of personal photographs and memories of life in the Gulf for South Asians and life in South Asia for Khaleejis, or people from the Gulf.

In the early 20th century, many Khaleejis went to India to make money

"I'm interested not only in how the South Asian experience in the Gulf has changed over time, but also how it has varied according to the country of residence and community," says Saldanha, a writer and Arabic translator.

"And I think it's important to include the stories of Gulf Arabs in pre-partition India. Nowadays we think of the movement of people going in one direction, but in the first half of the 20th century, India, particularly Bombay, was where many Khaleejis went to make money or get an education," she says.

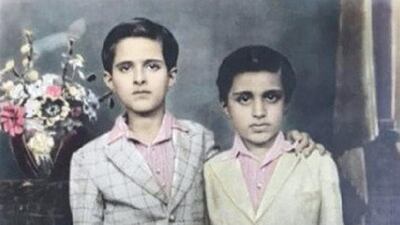

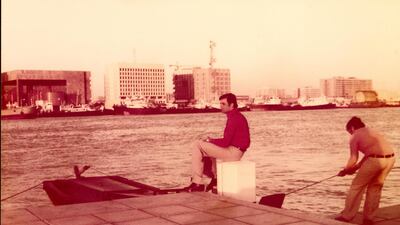

Saldanha sources from online archives, academic papers, books and submissions by South Asian readers who have shared photos of parents and grandparents.

“One thing I didn’t anticipate when I started this project was that I’d make connections with people whose parents or grandparents were in Muscat or Doha at the same time as my grandparents,” she says. “I’ve had a few conversations with people whose families have similar histories to my family’s. I didn’t get a chance to hear my grandfather’s stories about his time in the Gulf. He was there for 30 or so years, so that’s been an unexpected bonus.”

Saldanha hopes their memories will spur submissions from Khaleejis who have lived in South Asia. “I was in Dubai recently and when an Emirati man I met discovered that I had just come from Bangalore, he started telling me about his time studying there. Decades later he still remembered the names of streets and areas, restaurants, people he knew. He had a lot of fond memories of the years he lived in India and I think a lot of Khaleejis have similar stories to share.”

Those stories are timely, says Neha Vora, an associate professor of anthropology and sociology at Lafayette College in Pennsylvania in the US and author of Impossible Citizens: Dubai's Indian Diaspora. "Just as South Asians have been instrumental in the history of the Gulf, Khaleejis have long been involved in producing the distinct cultural spaces of the western coast of South Asia, as well as further afield. "In an era of rising Islamophobia in India, this is an important history to resurrect."

The account is inspired by community projects such as the Indian Memory Project as well as numerous Arabic Instagram accounts about Gulf history.

India and the Gulf: two regions that used to be one

Rather than divide according to state lines, the account links two regions considered one until the mid-20th century. "The decline of the pearl industry meant fewer Khaleejis travelled to India, while in 1947, the newly independent Indian government introduced laws to reduce foreign trade," says Rasha Al Duwaisan, an oral historian who studied the Kuwaiti community in mid-20th century Bombay for her master's thesis at Harvard University. "At the same time, the discovery of oil in the Gulf meant that many Khaleejis returned home to take on well-paid development opportunities."

The collection shows people at work, but also, and importantly, moments of play, and avoids a linear story of migrants, remittances and economics. Stories are snippets of the everyday: picking cockles on the beach, birthday parties at a new McDonald's in Riyadh and the family legacy of a sandwich and juice bar with keema sandwiches that attracted royal family members who got takeaways in bullet-proof vehicles.

There are colourful childhood memories: kids cycling behind Deira Tower on summer visits to their father, Khaleeji grandmothers buying sweets for the neighbourhood children or the joy of running in and out of tents at weddings.

“Since I was born in Dubai and lived here for a few years in the beginning, I thought of this place as a home always, even when I was living in Karachi,” Ismail Noor, a photographer whose father lived in Dubai, wrote. “Subconsciously, I always wished to be in Dubai. There are vignettes of memories, bits and pieces.”

Not just 'migrant workers' or 'expats'

Personal narratives make history relatable, says Al Duwaisan, whose own work explored those ties in the 2017 Hoisting Histories exhibition and in the Binary States collection.

“They give it a pulse. We can place ourselves in the shoes of our elders, envision how they spent their earnings, how they cooled their homes, what they worried about, what bedtime stories they were told. At once, we become closer to their reality and see the extent to which times have changed.

“It’s a more intimate way of engaging with the past.”

As Gulf states have more clearly articulated nation-building strategies, immigration has become a point of interest, says Vora. The dominant narrative is linked to the large-scale migration of South Asians in the '70s and '80s to the Gulf, first to Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, as states invested petroleum wealth into urban infrastructure. That gives a false impression that South Asian immigrants are new arrivals and foreign to the Gulf region.

"An economically driven narrative of temporary foreign labour migration is beneficial to Gulf states, which have increasingly promoted narrow versions of ethnic nationalism as their populations grow," says Vora. "It is also what is most readily apparent to academics, journalists and human rights organisations, who have tended to focus on the spectacle of Gulf urbanism at the expense of excavating the cosmopolitanism in which the region is rooted."

Family histories challenge the idea that immigrants are “migrant labourers” or “expatriates” who come to help build the infrastructure of rapidly expanding cities fuelled by petroleum wealth.

“These historical documents (photos, letters, memories) showcase how the Gulf and South Asia have a very long history of entanglement, with many people moving back and forth and making homes on either side of the Indian Ocean. They showcase the continuity of South Asian cultures and communities in Gulf cities and the active role of South Asians in producing the fabric of these societies alongside Khaleejis and other immigrant groups.”

Rather than relegate connections to the realm of nostalgia, Gulf South Asia’s collection runs to the present day, including a photo from last week’s news on the interfaith iftar meals at Dubai’s Guru Nanak Darbar Gurudwara for Sikhs and Muslim.

“My childhood is filled with tons of incredible memories – every day was an adventure like it should be for any curious child growing up surrounded by a community that nurtures them,” wrote Priya D’Souza, a creative consultant who grew up in the Gulf in the 1970s.

"I did not know I was Indian or that my family was Catholic until I moved to India when I was seven. Not once was I made to feel different from the others, and I didn't know I was."

Gulf South Asia is looking for contributors. Email gulfsouthasia@zoho.com or message @gulfsouthasia on Instagram