When it comes to the arts and the designed and manufactured world – the things we cherish, live with, live in and live on – how best can we balance the demands of modernity with a respect for tradition, a contemporary and cosmopolitan understanding of our increasingly globalised world with a profound sense of identity and place? In the Middle East and throughout its diaspora, what does it take to be modern and an Arab?

These are some of the deep-seated issues that contemporary artists and designers throughout the region must tackle, not least because the solutions they develop can have consequences that are often as important as they are unexpected. Most of us only notice these issues when they have not been dealt with.

We notice them when precious traditions are faced with oblivion, when neighbourhoods fail to meet the cultural needs of their residents or when technology conspires to make certain languages feel unwieldy or second rate.

It was a desire to champion the use of Arabic that inspired Huda Smitshuijzen AbiFares to establish the Khatt Foundation, Centre for Arabic Typography, in Amsterdam in 2004. It is dedicated to advancing graphic and type design throughout North Africa and the Middle East. “We started with the aim of modernising the image of Arabic design by making it contemporary and innovative, particularly in the field of bilingual typography,” AbiFares says.

“At the time, we were using two scripts together, but visually, they were not coherent. One looked very ancient while the other looked very modern, which made the idea of being modern and Arabic visually impossible,” says the designer, curator and academic who was living and teaching in Dubai at the time.

The problem was particularly noticeable in the UAE, where Arabic is more often employed alongside other languages, making it feel like little more than “a subtitle or a translation,” she says.

'If something is in Arabic, it doesn’t have to be traditional'

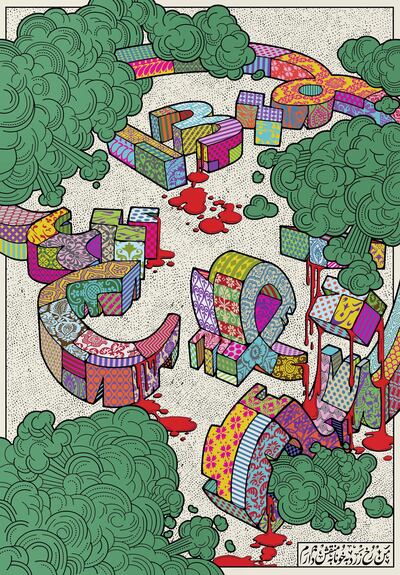

Since it was established in 2004, the Khatt Foundation has grown into a 5,000-member online design and research community that organises workshops and symposia, publishes books and mounts exhibitions such as Rasm: Contemporary Arabic Typographic Posters, 2008-2018, which opened on November 9 at 1971 Design Space in Sharjah.

Curated by AbiFares, the show runs alongside the inaugural month-long Fikra Graphic Design Biennial, the first graphic design-specific event of its kind in the region, which opened on the same day.

Featuring two specially commissioned multimedia installations from UAE design groups Rasm, which is the Arabic word for “drawing”, includes 56 posters that have been selected by AbiFares to reveal the experimentation designers from the region have engaged in over the past decade, a period she describes as a “new dawn” for Arabic typography.

“The idea that you would design an Arabic typeface for your own company was unheard of when we started, whereas now, things are miles ahead,” she says. “For a start, it has become an issue that people are really interested in, and not just Arab designers. International designers are now also interested in designing in Arabic.”

Read more: Here's what to expect from the first ever Fikra Design Biennial in Sharjah

Although the outcomes may express themselves as typefaces and graphic designs, Khatt’s mission, AbiFares insists, has always been to change perceptions and to convince Arabs and other people of the region that they can be modern while remaining true to their cultures and traditions.

“If something is in Arabic, it doesn’t have to be traditional, it doesn’t mean that it’s antiquated” she says. “When people feel that something is traditional they don’t touch it, and for me, that ’s a way of killing a culture, of making it extinct.”

'Living tradition is something that is constantly in a sate of innovation'

Despite AbiFares’s commitment to modernity, there is something in her words that chime with the work and ideas of the Saudi Arabian artist, craftsman and designer Ahmad Angawi, who has dedicated much of his career to the revival of “al mangour,” a traditional craft that had all but died out in his native Hejaz.

Mangour screens are an integral element of traditional architecture in Makkah, Jeddah and Madinah. They simultaneously act as veils and bridges between interiors and exteriors, a duality that even extends to the overlapping joints that are used in their construction, asheg and mashoug, or the loved and beloved. “If you don’t make traditional arts and crafts relevant to today, it’s almost like having a person who cannot breathe. They need to breathe in today’s needs and technology so they can continue as living traditions,” says Angawi, who is also programme director of the Jameel House of Traditional Arts in Balad, the historical district of Old Jeddah.

“The idea of living tradition is something that is constantly in a sate of innovation. The craftsmen of the past always worked with the best materials, the best craftsmen and they used their intellect to devise the best objects possible.”

The notion of breathing – exhalation and inhalation – and of marrying tradition with innovation, is central to Angawi’s most recent project, the creation of five walnut mangour screens for the British Museum’s newly opened Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World, a major re-display of the museum’s Islamic collections.

The starting point for the screen’s design is one the most fundamental patterns in traditional Islamic geometry, the breath of the compassionate, whose form changes, kaleidoscopically, depending upon how it is drawn.

Angawi worked with the project architects, Stanton Williams, as well specialists from Arup to create screens that would help to protect light-sensitive objects such as 14th century illustrated pages from the Persian epic Shahnama (Book of Kings) which is shown alongside monumental folios of the 16th-century Indian Mughal emperor Akbar's Hamzanama (Adventures of Hamza). "The screens represent Makkah, the heart of the Islamic world, which has always experienced an inhale-exhale relationship with the peoples and cultures that surround it," Angawi says.

“And they are now exhibited as part of a living Hejazi tradition in an Islamic gallery that displays artefacts from all over the Islamic world, from Africa to Asia.”

'People want to connect with their own nature'

Subtly different both in terms of their design and construction, each mangour is the product of a slightly different proportion of craft and innovation.

The most traditional, which is located in a gallery dedicated to historical artefacts, was made entirely by hand by a team that included alumni from Angawi’s alma mater, The Prince’s school of Traditional Arts and London’s Building Crafts College.

The most modern mangour, which sits in a gallery dedicated to contemporary works such as 21 Stones, a site-specific installation by British artist, Idris Khan, was constructed using computer-controlled cutting techniques developed in collaboration with the Madrid digital studio Factum Arte. "It was more difficult than we imagined. Each screen is constructed from around 100 strips of walnut joined at a 45-degree angle and each strip has to be cut on different sides," Angawi explains.

“Each time you want to make a cut the wood has to be turned over so that it can be cut accurately, which meant that each strip if wood had to be repositioned by hand four or five times.”

Angawi and AbiFares will both be taking part in the Al Burda Festival, a gathering of international artists, designers, curators and experts from across the museums and heritage sectors that is being hosted at Abu Dhabi’s Warehouse421 today. The symposium is designed to investigate potential futures for a wide range of cultural activities, all of which are inspired by or engage with the traditions of Islam.

In their own ways, Angawi and AbiFares both describe this culture as part of a cultural continuum that is deeper and broader than the confines of the religion.

Read more: Al Burda Festival will celebrate the future of Islamic art in Abu Dhabi

“Describing the world through words rather than images has always been a part of this region and the idea that text is holy is certainly older than Islam,” says AbiFares, momentarily looking back. “If you look all over the world at the moment, you can see a revival of interest in creating right now, and a return to the handmade, an urge to create objects that combine the mind, the body and the soul,” says Angawi, looking ahead.

“I think this is because people want to connect with their own nature, as humans, and I think traditional crafts have always been rooted in this, a connection between the maker and the earth.”