Bold figures draped in bright colours and frenzied patterns set against the sandy hues of their North African backdrop are the visual delights awaiting visitors to Hassan Hajjaj's latest exhibition. From his office in Marrakesh, the British-Moroccan photographer tells The National that the exhibit's title, Vogue, The Arab Issue, is a tongue-in-cheek nod to the monthly fashion bible as well as a critique of cultural cliches.

On display at Fotografiska in New York City, the showcase brings together five series Hajjaj has developed over 30 years, inspired by a photoshoot he assisted on in Morocco in the 1990s.

"I looked around and it dawned on me that the models, stylist, photographer, clothes were all European and Marrakesh was just this exotic backdrop," says Hajjaj. "So that's what really hit me. I was like, I'm going do my own sort of fantasy shoot with my people but really sharing their environment with traditional style and take it to the next level."

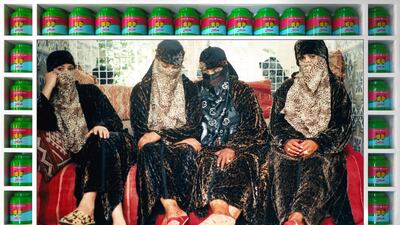

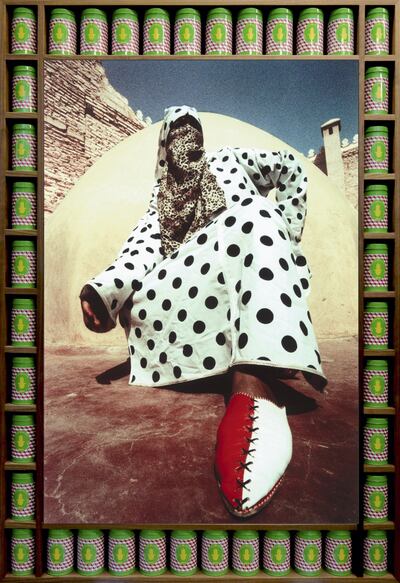

Using the polka dot, camouflage and animal print patterns popular in western fashion at the time, Hajjaj styled traditional Moroccan wares with these fabrics and asked local women to wear them and often parody the poses typical of European models. The results were an audacious juxtaposition of sensibilities, styles and cultural narratives that ring as true today as they did when he first began doing them.

“I always hope with our region I'm doing something positive, something that there's some truth to, there's some set-up, something funny, but I'm not making fun of our region or our own people. I want to be able to present this in a positive way, because, you know, we have a lot of negative things [to deal with].”

The title of Hajjaj's latest exhibit, he says, is also a reflection of the various socioeconomic issues plaguing the Arab region over the past decade. He wants to provide western audiences with a keyhole into something new to what they have been exposed to in the news.

However, as with most artists, Hajjaj doesn't like to elaborate too much on the meaning of his work, keen as he is to let the audience decide that for themselves.

“So for the viewer, when they see the work, they can see maybe something bizarre, something good, something cool, something scary, but I let them decide what they think of the show and how they see this issue,” he says.

Morocco's Andy Warhol

When Hajjaj began his career, his inspired, dynamic and trippy pop art aesthetic quickly earned him the moniker “Andy Warhol of Marrakesh”, not least because of his use of canned food from the Middle East to frame his art.

While he does not mind the comparison, even capitalising on it with his own Andy Wahloo clothing line, Hajjaj has said the canned goods motif is inspired by the repeated mosaic patterns in North Africa.

It was a long journey before he got to this point.

Born in the small fishing town of Larache in northern Morocco, Hajjaj was raised there until he was 12, when he moved to London in 1973.

After dropping out of school at 15, Hajjaj sold flowers, then clothes, at Camden market, also side-hustling on film and fashion shoots, as well as promoting the underground nightclub scene. Enmeshed in the city’s bohemian and multi-ethnic crowd, he soaked up the street artistry and music of the era and started his own clothing label, R A P (for Real Authentic People), in 1984 selling streetwear.

“I was just trying to solve, make, design and sell stuff to friends and people who wanted to wear the same stuff we did,” says Hajjaj, admitting this project included a lot of counterfeit designer logos, another of his instantly recognisable styling motifs now used in his artworks.

“When I started taking pictures, this is all I had, this is what I knew. So I was using this naturally, not thinking. I knew that using camouflage in the jalaba, for example, could look fashionable in one way or like a terrorist in another way, so I knew how to play on this vibe.”

It wasn't until the 1990s that his work really began to take off, after he returned to Morocco to reconnect with his roots and where he has been splitting his time, including during the pandemic, with the UK ever since.

Physically restricted, creatively free

After spending the first Covid-19 lockdown in London, Hajjaj has been in Marrakesh since last summer. Like most people, he admits the start of the pandemic was a panicked time, particularly as shoots and exhibits dropped from his schedule like dominoes and he worried about the staff he had to support.

“At the beginning, it was like everybody else, trying to figure out what was going on and how do you deal with this? Looking in the mirror, looking at yourself. And then it was like 'OK, how do I stay positive and healthy?'”

He took on commercial work he might not have ordinarily accepted as a means of overcoming the burdens wrought by the pandemic, and also took advantage of the downtime to pursue other projects.

"It took me time to adjust to working on my shows and projects from the other side of the world," he says. "Normally, I am travelling constantly and like to be involved both physically and spiritually. After working on projects through Zoom calls, it made me realise how amazing my team has been and that you have to have a great team on the other side in order to deliver a great show or project. Especially when you can't be there physically."

One of his most recent projects is a new brew brand called Jajjah – his surname spelt backwards – which he set up after partnering with renowned tea maker Amine Baroudi in Marrakesh. The tea is produced and packaged in the city’s industrial area of Sidi Ghanem, where Jajjah’s tea room will be. For those drinking at home, he's also developing an app that will match mood music to the 10 types of tea he's created and the packaging will be made of prints by other Moroccan artists he wants to promote.

The project is very much in line with the ethos he has previously espoused of giving back to the city he calls home.

“It made me realise that if there's any opportunity you can take to make some kind of change for yourself and to also employ people then there's a nice satisfaction to it.”

The making of 'Brotherhood'

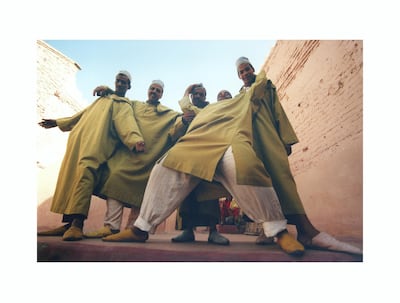

Hajjaj was also able to find that same sense of satisfaction when hiring a film crew to produce a project that has been 20 years in the making. His documentary, Brotherhood, is about the musical heritage of Gnawa, the Moroccan poetry, dance and religiously inspired music genre, and Capoeira, the Brazilian martial art that is similarly made up of dance, acrobatics and music.

By following a master in each of these forms, Hajjaj wants to give audiences a glimpse into the different ways these heritages of African slavery have travelled and transformed across the ages.

The first half of the film was shot in Morocco, and now Hajjaj is waiting for travel restrictions to lift before filming the rest in Brazil.

In the meantime, it has already been accepted to the next Sharjah Biennial.

Hajjaj says he's happy his creative juices kept flowing during the pandemic and is looking forward to showcasing what he’s done once the world goes back to "normal".

“I think it's good to kind of just, you know, believe in yourself and stay creative and try and finish off some projects,” he says.

While he's enjoyed his extended time in Marrakesh, Hajjaj says he's not quite done with London yet. Pandemic permitting, he will return to what he calls his "other foot" this summer. It is, after all, the home of his boutique, Larache, the creative hub from where his iconographic Moroccan clothing brand Andy Wahloo – also a play on the Arabic meaning "I have nothing" – is sold.

Nevertheless, there is little that can't be done online any more and Hajjaj sounds like a man who has enjoyed his life away from the big-city grind. He says he hopes to keep a connection to London, but ultimately spend more time in Marrakesh from now on.

“As I'm getting older, I'm realising I need to be back here,” he says of his homeland. “It's been nice for me to be in one place. It's been sometimes strange and you get the little moments you need to be up in the air and go somewhere, but in general you can plan things a bit better.”

That being said, he has also learnt to be adaptable amid the pandemic and is cautious about getting attached to any "best laid plans".

“You have to kind of be ready for the changes, you know, whatever comes your way.”