Last year, Beirut's Arab Image Foundation took receipt of a surprise package that was left on its doorstep. The delivery turned out to be a collection of classic photographs. "We didn't even know who brought it," says Marc Mouarkech, co-director of the AIF. "But, for us, it was a very important collection because it documented all the buildings in Beirut from the 1930s and 1940s."

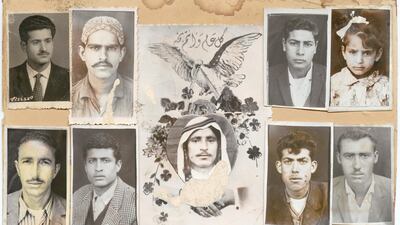

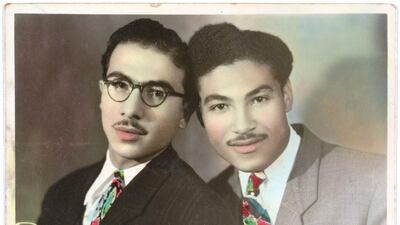

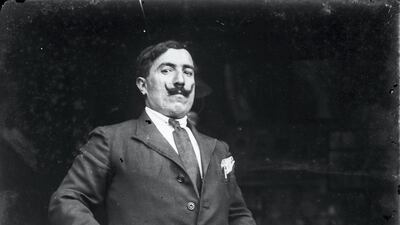

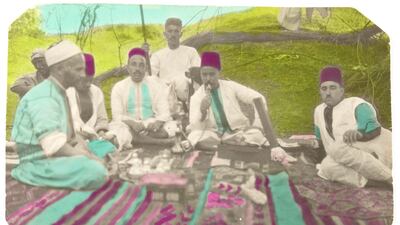

Look through the gallery above to see a few images from the Arab Image Foundation's comprehensive collection.

While this mysterious method of receiving images may not be an everyday occurrence at the foundation, the process of studying and archiving photographs very much is.

The Lebanese capital has been home to the AIF since 1997. Today, it has a 500,000-strong photographic archive, dating back to the 1860s, from much of the Middle East and its diaspora.

Last month, the organisation launched its new online platform which, according to its promotional newsletter, aims to provide "an enhanced user experience and increased accessibility to its online collections". The platform features four main sections and was two-and-a-half years in the making. It launched with more than 25,000 images and "objects" from 81 collections.

“The platform is a very important tool to start building a real community around the foundation,” says Mouarkech, 31. This new venture, he says, was borne out of a wish to engage fully with members of the Arab public so they “can interact with the images in a way that they see fit”.

"We want the people to feel that this material belongs to them," he adds of the AIF's large stock, a lot of which is well documented, some less so. "The collections come from families in the Arab region, studio photographers of the region and families that [emigrated] who are now part of the Arab diaspora. So, we want them to have an input, to actually add information."

With its sophisticated online presence, this non-profit organisation is a very different institution today than the one it was when it began more than 20 years ago. Lara Baladi was one of the very early members of the AIF. The photographer, archivist and multimedia artist recalls its modest beginnings. "When I became a member, there was no office and there was no director," says Baladi, who lectures in the art, culture and technology programme at America's Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

Forming a foundation

The Lebanese-Egyptian AIF former board member recounts introducing the founding members of the institution, Fouad Elkoury and later Akram Zaatari and Zeina Arida, to her cultural network and even to her own family as she moved back to Cairo from Europe and sought to “open doors to photographic practices in Egypt”. The shared desire to engage with the region’s history through photography was the catalyst that helped drive the institution to where it is today.

"The most obvious change that took place was that the foundation went from being a small initiative by artists and filmmakers to becoming one of the most instrumental, established institutions working in archives in the Arab world," explains Baladi, speaking from Cairo, where she resides when not teaching in the US. Indeed, the foundation presides over some of the most intriguing, playful and politically charged images and "objects" in the region.

The AIF kindly supplied The National with a variety of photographs from its bulging archive, including an image from Chafic Soussi (the reporter's grandfather), who captured a rally in support of then-Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser in Lebanon in 1956. Soussi, a professional photographer who owned and ran a studio with his brother, Anis, in Sidon, south Lebanon, assumed the role of something more akin to a photojournalist, documenting accidents, crime scenes and natural disasters, as well as political events.

This pro-Nasser rally was shot in a year when the Arab statesman caused international uproar by nationalising the Suez Canal in July 1956, followed by the invasion of British and French troops in a botched bid to re-take the canal in October. While the exact date of his photograph is not known, Soussi may well have captured public scenes surrounding the aftermath of one of these major global events during which time Nasser's political and personal popularity exploded exponentially across the region.

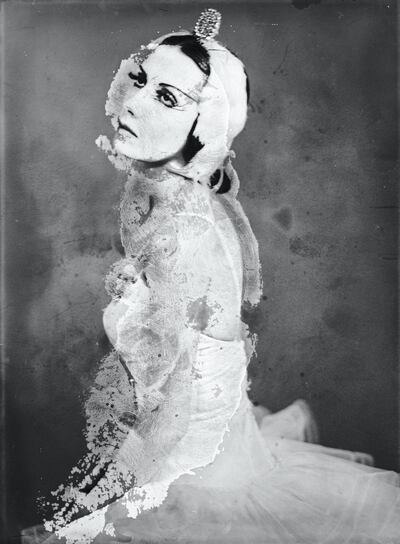

Another included image comes from Egypt's Armenak Arzrouni, shot some time between 1950 and 1960. Tamara Toumanova – a celebrated Russian-American ballerina and actress, who was nicknamed "the black pearl of the Russian ballet" – is captured by Arzrouni, a photographer of Armenian origin, who worked under the mononym Armand.

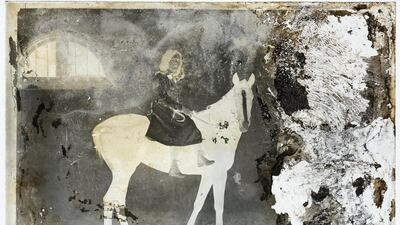

The Arab diaspora also features in a sizeable proportion of the AIF’s archives, elegantly illustrated by the inclusion of a 1950s portrait from Alfredo Yazbek in Mexico. Studio Yazbek, whose owners were of Lebanese descent, was a prominent portrait studio in Mexico City that opened in the 1930s and closed some four decades later.

It was a particularly poignant photographic project that saw Yasmine Eid Sabbagh get involved with the foundation. In 2007, the artist was working with Palestinians at a refugee camp in southern Lebanon. After engaging with the AIF for her project, A Photographic Conversation from Burj al-Shamali Camp, she found herself drawn into the foundation's inner workings. Today, she is president of the AIF board.

Yet, she explains, with no financial support from the Lebanese government, the organisation has had to function "with very little means".

“The foundation was an initiative that was driven by artists and practitioners,” says Sabbagh, who is of mixed Lebanese, Palestinian and German parentage. “It’s a self-determined project in a country in which this is really necessary.” Of the AIF’s comprehensive and stunning archive, Sabbagh says that her “passion is for personal and ‘vernacular’ photography”.

“There is something very sweet about these photographs from people’s everyday lives,” she states. “You have photographs that have a certain moment of intimacy, which is what I really enjoy when I look at these types of images.”

As alluded to by Sabbagh, financial constraints remain at the heart of the foundation's ongoing challenges. Mouarkech says that monetary support from international institutions "has reduced enormously" due to the likes of budget cuts. And although AIF has massively scaled down its own efforts to add to its weighty collection, he adds that the public perception of the art and photography market as a means for financial gain remains problematic for institutions like his.

"People now understand that photographic collections have value," says Mouarkech. "And this changes the way people perceive their collections. They think of them as moneymakers, and are not interested in [donating] a collection for it to be preserved – and are only interested in selling a collection."

The AIF's current projects include work on a Lebanese Civil War archive. While the platform itself was successfully launched in May, the foundation plans to upload about 12,000 images each year as it seeks to digitise its entire set.

Indeed, the AIF’s visible presence is its photographs. Away from financial and practical concerns, the institution sparkles through an archive that, as far as its more “everyday” images are concerned, all share a common humanity, argues Baladi. “What’s reassuring in the foundation’s collection is a universal sense of belonging, of recognising and identifying to others,” she says. “These are patterns that cut through social class and religious beliefs and institutions.”