I’m going to try to put my childhood into visual context: I grew up in what most definitely was a museum and what most certainly seemed like an endless vernissage with artists, intellectuals, cultural aficionados, wealthy patrons and journalists mingling in our home.

This ambiance was largely due to my legendary mother, Sherwet Shafei, whose foray into the art world began in 1960 with Egyptian television. She hosted a weekly show on modern Egyptian art. My mother fell in love with the genre, became a confidant to its artists and avidly collected their work (making her collection one of the finest in its field).

In 1989, she took over Safarkhan Gallery, founded in 1968 as a space that exhibited Islamic art, and which she baptised as one of Cairo's – and the world’s – preeminent galleries to explore modern and contemporary Egyptian art. So, my life was and still is replete with visual delight and intellectual stimulation.

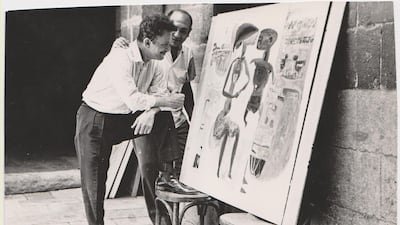

As a child, I remember staring in awe at the art around me. So intrigued, I was desperate to know what the artists were trying to say through their work. Amidst the sound of chatter, laughter, clinking glass and music, the five-year-old me remained oblivious to the many anonymous faces mingling in our home, save for one, a very gentle-looking one, and it belonged to Hamed Nada.

He smiled continuously and emanated a pureness and a warmth, as though there were an aura of kindness surrounding him. I guess he also stood out because of his height and the helmet of white hair on his head, which to me, made it seem as though he were glowing. Actually, he glowed because a light radiated from him.

Nada was always laughing; he laughed and talked at once, making him such a bubbly and pleasant person. Every time he showed up, I became giddy and just gravitated towards his energy.

director of Safarkhan Gallery

Nada was low-voiced because of a speech and hearing impairment, making it difficult to hear what he was saying, but it didn’t matter because somehow my parents and I understood. Nada dealt with it well, largely because he was a pure soul and one who accepted his fate.

He talked in such a cultured way, and always laced with humour. Very quickly, I got the impression that he wasn’t just an artist who frequented our home, but a sincere friend to my parents. I feel so honoured to say that he was my friend, too.

My mother, being her intuitive self, noted a strong connection between Nada and I, and in the name of further nurturing my art education, promptly arranged for weekly visits to his studio in Gamaliya, in Old Cairo, a Unesco World Heritage Site also known as Islamic Cairo.

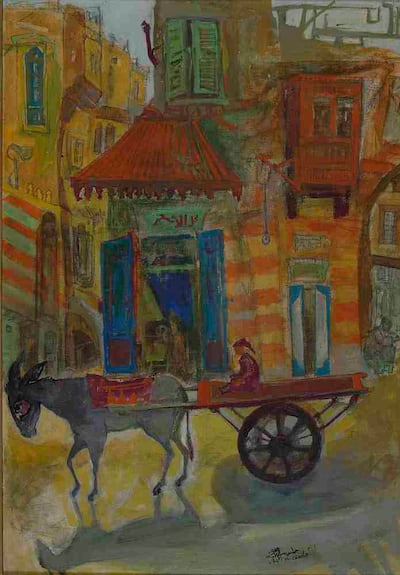

Nada was born in the nearby Al Khalifa neighbourhood and was brought up in a devout home to a father who was a sheikh. The everyday sights and sounds of different areas in this religious vicinity, including the Al Sayeda Zainab Mosque, came to have a lasting impact on him – it can be felt in the djinns, symbolism and superstition within his stylised figures of later works.

At school, Nada gravitated towards art, psychology and philosophy, and as fate would have it, met Hussein Youssef Amin, an artist, mentor and scholar, who gathered his proteges at his home on a weekly basis and encouraged them to speak for those less fortunate.

In 1946, together with fellow artists including Samir Rafi, Kamal Youssef and Abdel Hadi El Gazzar, Nada formed the Contemporary Art Group, which celebrated Egyptian-ness through socially realistic works that tackled popular tradition and folk symbolism.

Two years later, in 1948, Nada joined the School of Fine Arts in Cairo, and in parallel, worked as an illustrator and critic to Al Thaqafa, a popular periodical. After graduating in 1951, the Egyptian working class dominated his paintings, and in 1957, he taught at the faculty of fine arts in Alexandria University.

He was awarded a scholarship in 1960 to study mural painting at the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Madrid. He returned to Cairo where he taught at his alma mater, later heading its painting department and continuing to teach after his retirement in 1984. It was during this time that my visits to his studio began.

Where our home was a carefully curated, pristine and organised space, Nada’s studio was a chaotic, awesome expanse. Looking back, his bedlam reminds me of a verse in Shakespeare’s Hamlet: “Though this be madness, yet there is method in it.”

Immediately, I understood that his studio was his sanctuary; it was where he spoke through painting and where he reconciled the unkindness he’d seen outside. Washed with light, the space resembled an ancient Roman relic – at least that’s the sense I got because it felt packed with history and stories.

Being there was liberating for me on so many fronts: I could pick up brushes, dip my fingers in paint, open drawers and cupboards and never felt bored. In there, I felt like a friend, and he didn’t speak to me as a child. I wholly related to his paintings and why wouldn’t I? The cats, exotic birds, musical instruments, lamps, chairs and dancing people all looked like things I would draw.

The time between each visit felt like an eternity. As I yearned for the next trip, somehow, though it was palpable that his paintings oozed a rhythm and a prance, and transmitted an exchange between all elements, I started to feel like I could hear someone screaming, someone wanting to be heard.

I could sense there was pain, and I knew it came from Nada’s empathy with the plight of his countrymen, and his bad luck with women. He knew he was different [and so did we] and perhaps that made him feel like he had less to offer, meaning he struggled more.

The thing is, Nada contributed something that no one else did: a unique language, a Nada semantic, which he forced us to decipher. And once we did, we understood that painting for him was a healing mechanism, but it was an aide-memoire for us to really see the plight of our brethren. Some artists remain artists, others become great, and Nada was brilliant. I can still see him glowing.

Remembering the Artist is our series that features artists from the region