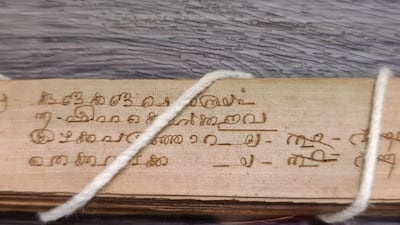

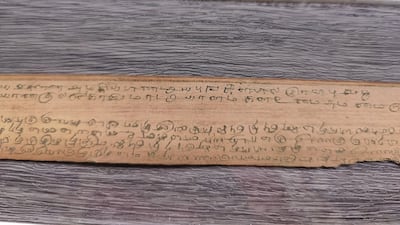

Deep incisions dance along a single palm leaf in a cursive, curly script that is inked and behind glass — this may look like any other palm leaf manuscript, although it is anything but.

This particular piece chronicles a battle that changed the fate of would-be Dutch colonisers in India. It was the storied Battle of Colachel, where the Travancore king Marthanda Varma defeated the Dutch East India Company, 20km from Kanyakumari, the land’s end of India, ending Dutch ambitions of expansion in the subcontinent.

This slice of history is being exhibited at the newly opened Palm Leaf Manuscript Museum, housed in a series of tiled roof cottages set around a quadrangle, at the renovated Central Archives Fort, in Thiruvananthapuram, the capital city of Kerala.

Touted as the world’s first palm leaf manuscript museum, it is a repository of records of various facets — from sociocultural to administrative — of the erstwhile Travancore state, straddling 600 years from 1249 to 1896.

A brief history of palm leaf manuscripts

India’s rich knowledge has been passed down generations, through various oral and written traditions, using materials including stone, copperplates, bark, palm leaves, parchments and paper. Palm leaf manuscripts were the earliest writing materials in India and South-East Asia, dating back to the fifth century BC.

Today, there are millions of palm leaf manuscripts in India in various languages and dialects from Malayalam and Sanskrit to Devanagari and Tamil. Many manuscripts are stored in temples, religious institutions and libraries across the country, and contain information on everything from land records to grammar, poetry and even philosophy. Many have been exposed to the vagaries of nature and deteriorated.

Usually dried and smoke-treated palm leaves of the palmyra palm or talipot palm were used. Two species of special palm leaves were selected, then boiled in hot water, dried in the shade and cut to one metre in length, and smeared with lemon grass oil to prevent them from deterioration and termites.

Palm leaf manuscripts were inscribed with a metal stylus and then inked. Each sheet had a hole through which a string could pass, and then they were tied together like a book, between two wooden planks. A palm leaf book could last for even as long as 600 to 800 years, unless it decayed due to moisture, insects and mould, for example.

Inside the Palm Leaf Manuscript Museum

The museum is curated by Keralam, the Museum of History and Heritage, and housed in a 300-year-old heritage building which once used to be a jail. The manuscripts stored here are in the ancient Malayalam script and some of them are displayed as a bundle, whereas others are just a single leaf. The team in charge of the project had to sort through as many as 15 million palm leaf manuscripts, from record rooms throughout the state, and restore those that were in poor condition.

The museum has eight galleries, separated by theme, and 187 rare and ancient manuscripts are stored here, in special aerated glass cases with controlled humidity and protection from pests, with a plaque explaining its contents.

The exhibitions are divided into themes such as the history of writing, land and people, administration, war and peace, education and health, economy, art and culture, and Mathilakom Records, which includes details of the famous Shree Padmanabhaswamy Temple and its vast wealth. Each display has a magnifying glass, making it easy for visitors to see the writing and script up close and come with QR codes that can be scanned for more information and videos. Each room also has a kiosk where you can download or print the entire transliteration of a palm-leaf manuscript.

One manuscript is from 1864, when the king wanted to empower the local women and gave them rupees 300, a princely sum in those days, to start an enterprise. Another points to how the kings tried to prevent sati, an old Hindu practice in which a widow sacrificed herself by sitting on top of her deceased husband's funeral pyre. One manuscript restricts travel between the regions that are now Tamil Nadu and Kerala states, during a smallpox outbreak, while another mentions officers fined for late attendance.

“The museum traces the history of the state and also the progress of the local Malayalam script which evolved from earlier versions,” explains archivist KS Nandakumar.

The History of Writing section traces the evolution of the Malayalam script, as well as talks about how history was recorded down the ages. There are styluses that were used to write on palm leaf and bamboo carriers that transported the bundles of palm leaf manuscripts to the palace for the king’s signature.

'Indians have woken up to these treasures'

For many decades, interest in these valuable manuscripts had faded, until on February 14, 2007, the National Mission for Manuscripts launched the National Database of Manuscripts, which contains information on more than a million Indian manuscripts. Now it aims to conserve, as far as possible, each document, whether in a museum, library, temple, madrassa or private collection. They work through 57 manuscript resource centres and trained conservators.

In Bangalore, the NGO Tara Prakashana was started in 2006 by PR Mukund, a renowned professor with a doctorate in electrical engineering, who divides his time between the US and India, and has a palm leaf digitisation project where they have patented a technology called Waferfiche to archive images.

The team also uses cotton acid-free archival paper that can last for 200 to 300 years, to copy and print the old manuscripts. They have also used silicon wafers to save the manuscript in digital form and the trust has so far preserved more than 3,000 palm leaf manuscripts.

“It's impossible to estimate the number of palm leaf manuscripts across South India that are in existence, as many families and scholars have ancient palm leaf manuscripts in their private collections, and many religious institutions and libraries have extensive collections not known publicly," says Mukund.

“The main problem in these manuscripts is the lipi, or script, as many of them are no longer used, or are understood by very few people. It’s a challenge to find a scholar who can transcribe them into a script that can be understood now.

“For hundreds of years, we have ignored this rich legacy, but suddenly Indians have woken up to these treasures and decided to preserve them and digitalise them for posterity. In these manuscripts, one can find an amazing amount of practical knowledge with great depth, that is applicable to all aspects of life from medicine to astrology. Rediscovering all this ancient knowledge and applying it to our lives today is going to be exciting."