As Expo 2020 Dubai draws to a close, it is the end of a chapter for architect Daniel Hajjar, the managing principal for HOK across Europe and the Mena region.

HOK was the lead design firm on the original master plan, which was submitted to World Expos in 2012, with Dubai winning the bid on November 27, 2013, against four other cities.

Mr Hajjar will never forget that moment.

“I was actually on a plane coming in to land in Dubai, and there were fireworks going off all around the city. So that’s how I knew they had won it,” he tells The National.

When the world’s fair ends on March 31, the 4.38 square-kilometre area will be repurposed to host 145,000 residents and workers.

More than 600 start-ups and small businesses from around the globe already want to be the first tenants of District 2020, the name of the legacy site, which will open in October.

The $8 billion Expo development forms a large part of Dubai's 2040 Urban Master Plan, with the area helping to house a projected population of 5.8 million.

“[An Expo] is a significant investment for Dubai to make. So, fundamentally, it’s the responsible thing to do to try to keep as much of it as you can,” says Mr Hajjar, who divides his time between the firm's London and Dubai offices.

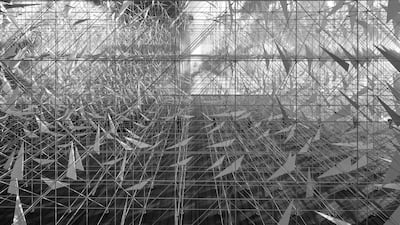

What is key about this transformation is that 80 per cent of the structures will remain in some form, with the aim of creating a sustainable development as a focal point of the original master plan, says Mr Hajjar.

It is also a fundamental difference between Dubai’s event and previous expos, when the majority of the pavilions were typically taken down at the end of the six-month event.

Mr Hajjar says that is done is in accordance with Bureau International des Expositions regulations.

“When expos are held, one of the rules is that the pavilions put up have to be taken down within six months of the completion of the expo,” said Mr Hajjar.

“You can appreciate, there was a fair amount of capital invested, there was a fair amount of infrastructure invested. So the question really was, how can we actually leverage what has been invested in terms of creating a legacy plan for the site?”

This formed one of two changes to the original master plan HOK put in place after Dubai won the bid.

The first was to accelerate building Dubai World Central – the airport at the heart of the project – and the second was tweaking the master plan to ensure the design was sustainable, with the site able to continue its life long after the Expo visitors left.

The HOK team visited other expo cities to understand their strategies after the events ended. In Shanghai, for example, they found 95 per cent of the pavilions had been removed.

“As a result, Dubai is one of the first Expos to change that rule fundamentally," Mr Hajjar says.

“Not only is [removing everything], an irresponsible thing to do from an environmental perspective, it also creates this gap within the city fabric.”

HOK came up with the first legacy plan, asking itself some key questions such as “how does the site transition into being part of your city because eventually, after the event, you're going to be relying on your citizens who live there to make it viable", says Mr Hajjar.

While the HOK initiative saw the site become the home of the Dubai International Exhibition Centre, other firms have since decided the main elements of that plan.

Last month, David Gourlay, director of architecture for District 2020, said the site would become the UAE’s first “15-minute city", with residents able to walk or cycle from end to end without the need for a car.

Meanwhile, the UK has already said it will open a hydrogen innovation centre with the UAE on the legacy site, while Italy will run a “renaissance” legacy project to preserve archaeological artefacts and art recovered from war zones.

Even before the world's fair began, chief experience officer Marjan Faraidooni said some of the largest buildings on site were built with the future in mind.

That is certainly what Mr Hajjar was asked to create, with the architect delighted to see elements of his original design during a visit to Expo in November.

“It was exhilarating," he says. "The fact that you remember either drawing the lines in the design or discussing the design and then seeing it come to fruition – that's why you're in this profession. That's what makes it exciting.”

That focus on sustainability was key from the outset, says Mr Hajjar. It formed one of its sub-themes along with mobility and opportunity, with the extension of the Dubai Metro central to making it all happen.

“How can you have a sustainable Expo, if people are going to get in their cars and drive there?” says Mr Hajjar, highlighting the necessity for the extension of the vital transport link.

The build and delivery of the event is also testament to Dubai and the UAE's wider commitment and drive when it comes to ensuring a project goes ahead.

“That's one thing I give the Emirates and region credit for – once they agree a plan and go forward, they execute it very well," says Mr Hajjar.

"And the way the site is structured, the way it's organised – not just the hardscape of the site, but the way they are dealing with people is admirable."

Other lessons his team learnt from examining previous expos included finding a way to keep visitors queuing at pavilions entertained.

“We knew there would be more demand on some of the more popular pavilions,” he says.

It was about “how you actually engage the public realm, the landscape, the physical structure of the plan, to keep people engaged, so they don't feel like they've wasted” time, he says.

While the master plan is one of HOK’s prouder developments for the Emirates, Mr Hajjar puts the total value on the megaprojects the company has worked on in the country at Dh4 billion to Dh5bn ($1.08bn to $1.36bn).

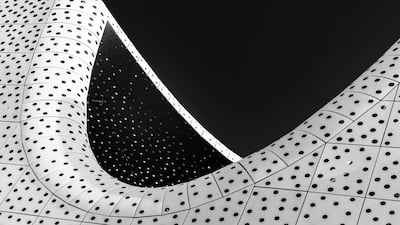

Notable projects within that figure include the design of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company headquarters on the Corniche in the capital, a project that was completed in 2014.

“One of the directives was to create a timeless symbol,” he says.

“That's a huge challenge because in the era of every building twisting or shouting, the more bizarre the shape, the better, I think the elegant portal of Adnoc will stand the test of time.

"It is simple, timeless, classic and yet still expressing itself in a modern manner as opposed to hearkening to the past.”

One of Mr Hajjar’s favourite projects because it "set the benchmark in terms of quality" in the country, is the six residential, high-rise towers and 64 villas completed in the first phase of the Dubai Marina community in 2004.

There is also the Etihad Arena on Yas Island, the Middle East's largest indoor arena, with other regional achievements including the 80-storey Public Investment Fund Tower in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, the Central Bank of Kuwait, and the Yiti and Yenkit residential and resort development in Oman.

While most of the company's Middle East work is now focused on Saudi Arabia, which is undergoing a rapid transformation as it strives to diversify its economy away from a reliance on hydrocarbons, one theme stands out across all of HOK's developments: sustainability.

“Sustainability for us is something that we've been doing pretty much since the founding of the firm,” says Mr Hajjar.

“HOK as a practice ... wrote the first textbook, to teach sustainability in universities and it's remained very much a fundamental mantra to whatever it is that we do."

This has helped spur the company's presence in the GCC to see the "level of consciousness related to sustainability really ramp up".

"In Abu Dhabi, in particular, when they introduced the Urban Planning Council and the Pearl Rating System for sustainability, it was the first government body in the region that formalised their sustainability protocols and goals," Mr Hajjar says.

"After that happened, you began seeing a lot more different areas or regions within the peninsula looking at implementing those."

Now the UAE is looking towards hosting its next mega event: the UN climate change summit, Cop28, in 2023.

“This is another important event,” says Mr Hajjar.

“It's one of these things where someone would say, 'Well, why are we having a Cop in the middle of the desert?'

“That is something that the world needs to tackle, because there's increasing desertification happening, globally and water resources are probably going to be more valuable than oil in the future.”

For the Cop28 organisers, Expo is an illustration of how successful a mega-event can be.

Not only has it succeeded on the sustainability front, it overcame the enormous challenge posed by the Covid-19 pandemic, which forced the organisers to delay the event until October last year.

Ultimately, there are two lasting messages that Expo will leave behind, Mr Hajjar says.

“One, it is the first Arab country to host an international event like this,” he says.

The second is that many wondered whether the expo concept “had had its day", he says, because anyone who wants to find out information can simply look it up on the internet.

But with the pandemic forcing the world to rely on remote working and video calls “Expo Dubai really created an environment where everybody realised how important it was for people to get together”, he says.

“To a certain degree, the Zoom and Teams' environment may have contributed to its success inadvertently, because everyone was fed up with being virtual all the time," he says.