DHEISHEH, WEST BANK // High in the sky above a narrow, noisy and congested street in this West Bank refugee camp is a veritable paradise of green, shade and quiet.

Throat-burning exhaust, blaring horns and clinging dust seem to choke the life from the Palestinians navigating the street below. But atop this overcrowded, dilapidated apartment block is a garden that bursts with cucumbers, bell peppers and strawberries - and hope.

With the help of makeshift greenhouses, more than a dozen Palestinian families have started to farm on the roofs to blunt the harshness of a financial crisis that has crippled the Palestinian Authority (PA) and drained the pocketbooks of the refugee camp's 13,000 residents.

Here they tend to their modest crops with remarkable dedication. Not only does rooftop farming mean less cash spent for food. For many, it is a remedy to the claustrophobia of camp life.

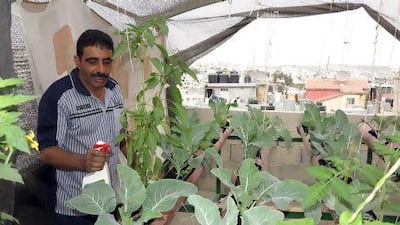

"I dream of this way of life," said Khader Najjar while watering rows of cabbage, spicy peppers and green beans in the garden on the roof of his four-storey building. From his vantage point, he looked across at the skylines of Bethlehem and Jerusalem.

Mr Najjar, a 46-year-old labourer, said his wife cooks the vegetables he harvests. They also give some to his brother, a teacher in a PA-run secondary school.

The funding for Mr Najjar's greenhouse was supplied by Karama, a Dheisheh-based non-profit organisation. It paid roughly US$900 (Dh340) for each of the first 15 greenhouses given to Dheisheh residents. Since the programme began in May, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) and Lush, a British company specialising in home-made cosmetics, have joined Karama in supporting it. An additional 85 greenhouses will be built in Dheisheh and another refugee camp.

"It has become wildly popular," said Loay Abdalghafer, the project manager for Karama.

The rooftop greenhouses consist of netting and metal staves, and four, 3-metre, heavy-duty pipes. The pipes are sheared in half lengthways and laid across the roof under the nettings. They are then filled with potting soil and connected to a water tank.

One of the aims of the programme is to teach skills to help Palestinians cope with regular crises resulting from life under Israeli occupation. But Karama also wants Palestinians to reduce their dependence on foreign-financed non-governmental organisations and activist groups, which it says often push confusing and competing political agendas.

Mr Abdalghafer does not exclude the PA, which is heavily dependent on foreign aid from this list. "Many of our problems come from all the conditions of this aid money, and so we teach farming to help people to learn to depend on themselves," he said.

One example of the ill-effects of this dependence, he said, was the US's withholding of some $200 million in aid last year as punishment for the Palestinian leadership's attempt to win statehood recognition at the United Nations.

Mr Abdalghafer acknowledged that an end of foreign support for the Palestinians was neither possible nor desirable. He called Karama's rooftop farming programme a "political message" aimed at encouraging self-reliance.

The initiative has direct humanitarian benefits, said Mustafa Younis, UNRWA's representative in Dheisheh. More than half of employed adults in Dheisheh are working for the PA, and its financial ills have led to a worsening of poverty and employment in the camp, Mr Younis said.

That is why UNRWA has agreed to fund the purchase of at least 50 more greenhouses. "Growing your own food can be very helpful," he said.

Earning about $70 a week cooking at a local restaurant, Hajjar Hamdan enthusiastically took up the offer of a rooftop greenhouse.

After her greenhouse was constructed, Ms Hamdan began planting everything from tomatoes and cucumbers to spinach and courgette.

Karama also gave her a class on the basics of farming and then, after weeks of careful cultivation, she began reaping the leafy benefits.

"I love greens, and I love to plant," said Ms Hamdan, 60, who lives with her mother and sister. "It's natural, no chemicals, no hormones, and when I need something, I just go upstairs and pick it."

Follow

The National

on

& Hugh Naylor on