NEW YORK // One hundred years before the uprising against Bashar Al Assad began in Syria, the Arab-American novelist Amin Rihani published a prescient novel addressing “Arabia’s spring”.

Drawing from his experiences in America’s diverse society, Rihani, who was from what was then called “Ottoman Syria”, warned that sectarianism instigated by foreign powers would divide Syrian Arabs of all religions and prevent them from attaining self rule.

Rihani, who was from what is now Lebanon, was part of an Arab literary milieu in New York at the turn of the 19th century that included Khalil Gibran and others. They were one thread of the rich social fabric of America’s first Arab enclave, Little Syria, that produced wealthy merchants, intellectuals and writers, and even the first Linotype machine to use the Arabic script, a Manhattan innovation that transformed communication in the Middle East.

The final physical remnants of this vital but oft-forgotten neighbourhood – and the role of Arab-Americans in the country’s formative history – however, could soon all but disappear.

Most recently, the historians and activists who have struggled to preserve the few remaining buildings on Washington Street in lower Manhattan, only blocks from the World Trade Centre site, have fought to push the September 11 Memorial Museum to include the area’s diverse history in its collection.

The museum, which has received tens of millions of tax dollars, is scheduled to open in April as part of the larger September 11 memorial site. Part of its mandate is to document the history of the area that surrounded the twin towers, but so far museum executives have refused to include Little Syria’s history or display any of its artefacts.

One of the dominant legacies of the September 11 attacks has been the rise of Islamophobia in the US as well as discriminatory, and many critics say unconstitutional, counterterrorism and surveillance practices that target whole Muslim and Arab communities without any specific suspicions.

By excluding Little Syria from its exhibition the museum is missing an opportunity to address this legacy by placing Arabs and Muslims at the heart of the great American narrative, as insiders, not hostile foreigners.

“It could be a valuable way to teach people about who the Arab Americans are and explain their long history here,” said Todd Fine, a historian and Rihani scholar who helps run the Save Washington Street preservation group. “The museum [curators] don’t seem to see why people are concerned about this and why including even a mention of Little Syria would be an elegant way to address that.”

The museum has refused, saying that the idea was posed too late to include in the final design.

“If you don’t want to include it in the museum, why not put up a quote from Gibran or Rihani on the wall, something about bringing different religions together?” said Mr Fine. “That was a non starter, they ignored it.”

Months after Al Qaeda hijackers flew two planes into the towers on September 11, 2001, killing more than 2,600 people, a crew clearing rubble from the site discovered the cornerstone of one of Little Syria’s original Maronite churches.

The museum has also declined to include the cornerstone in its permanent collection. But after months of pressure from Save Washington Street and others, the museum said it would consider including the area’s Arab history in a temporary oral-history exhibit at some point in the future.

“It’s a terribly missed opportunity,” said Moustafa Bayoumi, author of How Does It Feel to be a Problem? Being Young and Arab in America. “I can’t speak to what their exact motivations are, but it’s fair to say that in the climate that we live in today, it’s very easy for anything Islam or Arab-related to become politicised to an absurd degree.”

Mr Bayoumi lamented the continuing apathy of many Arab Americans that prevents them from organising to save the remaining structures on Washington Street.

“It’s a shame the Arab-American community is not as involved as it should be to retain and memorialise and use the site to educate about the long and deep history of Arab Americans in this country,” he said. “I think most Americans would be totally shocked to know the depth of the intellectual production that has come out of the Arab-American community for so long.”

But that lack of involvement is beginning to be reversed by young Arab Americans who came of age in post-September 11 America.

Carl Antoun, 22, a university student from Brooklyn, says his grandmother grew up in the heart of Little Syria on Washington Street. Her family came with a wave of other Arabs from what is now Lebanon, to escape increasingly harsh Ottoman rule as well as the withering of the local silk trade that was vital to the economy.

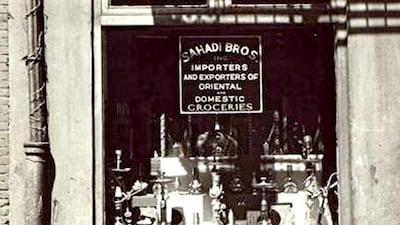

New York’s Arabs established a thriving enclave, with Arabic newspapers, grocers that sold spices and specialities from home, restaurants and cafes where people shared views on the politics of the rapidly changing societies they left behind, but refracted through their experiences here.

Eventually, as people prospered they moved to suburbs in Brooklyn, and in 1940, most of the area was destroyed to make way for a major tunnel. The rest was torn down in the 1960s with the construction of the World Trade Centre.

Today all that remains are three buildings huddled beneath tall hotels and offices. There is an Arab Melchite church, designated by the city as a historic landmark, as well as a building that was once an Arab community centre and an old brick tenement.

The church was used as an Irish bar for the past 30 years, but it is now a staging area for construction workers building a towering hotel next door. Mr Antoun, who helps run Save Washington Street, said he hopes that they can convince the city to designate the two other buildings as historic structures and save them from being demolished by their current owners.

The group is trying to raise money to buy the buildings and turn them into a museum that would celebrate the area’s Arab heritage, and its role in shaping the city and the world beyond.

While they have not managed to generate much financial support from the Arab-American community or those abroad, a city council member has for the first time agreed to ask the landmarks preservation commission to hold a hearing on the matter, something the commission had refused to do.

The group also helped refurbish a small park nearby that they hope to turn into a memorial to the renowned Arab writers and intellectuals such as Rihani who once called Washington Street home.

“Arab Americans don’t really have anything at all and they’ve been here just as long as the Jews, Italians, Irish. They started coming in the 1880s,” said Mr Antoun. “It’s very important for us to look back and say: ‘Wow, we’ve been here for a long time and we deserve a place in history.’ That’s why this is important for me, it’s personal.”

tkhan@thenational.ae