Consider the life of the nomad, who has no attachment to built forms. Belonging, for a nomad, is never to a place; his reference points are derived from his tribe. He has no “home”, and no accomplishment apart from his lineage and the proof that it has survived through time.

This lack of belonging to a place is something that modern societies have tried to overcome, since tribalism has perilous social consequences. Wise urbanism, especially in a country like Syria, must set out to overcome the pathologies that arise from tribal ways of thinking, and to generate in their stead a sense of belonging to a place, and being part of the community that has made its home there.

To do this, our architecture must pay due attention to the sense of beauty, and the social significance of built forms, as well as manifesting a healthy “national pride”. We should not be building our cities as though they were the temporary shacks of nomads.

Of course, the situation in Europe is in no way comparable to that in Syria and elsewhere in the Middle East. Nonetheless the so-called “advanced countries” are also struggling with problems due to mass immigration and the need to adapt to pressures that the infrastructure was not built to accommodate.

I read about the heterogeneous urbanism, involving zoning by race and religion, in the northern British cities, and in Paris and other major French conurbations, and I recognise the beginnings of the kind of instability we have witnessed so disastrously in Syria.

We might think we are different from each other, but the truth is that we are all human. Does it then follow that the European aversion to receiving more immigrants has no justification? If it is an expression of tribalism, then, yes, we need to be wary. But if it is in defence of a long-fought-for sense of accomplishment, then no one should argue with it.

Whether we like it or not, a significant number of immigrants are leaving behind places that have struggled with their accomplishments, and have no clear “point of departure” from which its citizens can orient themselves in the world. It is just such immigrants who are most likely to suffer from abuse and prejudice – not simply because they are different but because they no longer have a “back” to lean on. They are consequently much more likely to settle in marginal zones of cities, to live in cliques and thus prompt the wider society to increase their sense of isolation.

Without the collective accomplishment that would support them and invite respect from the world and from themselves, they will always be the underdog trying to find a “home”. And, if they cannot return home quickly, what of their children? The next generation would have to move towards a psychic state that has the relevant departure points. Will this new generation be able to dissolve into the new society, or will it always struggle for an accomplishment of its own? How long might that take? Would it happen as a smooth metabolic process, or would it be more like a chemical reaction with the experiment exploding at the slightest miscalculation?

Although so many people were compelled – in every sense of the word – to leave their homes in Syria, there were a considerable number who chose to migrate to “gleaming” Europe, dreaming of a ready-made future there, only to be culturally shocked because they had been accustomed to receiving much more for much less effort.

They remembered the generosity of their motherland. In Syria, you can literally throw a seed in the soil, forget about it and come back to find a sapling. Food is available the whole year round: every month – not just every season – an entirely new array of food grows out of the ground.

Its people have also accumulated expertise over the centuries on the Silk Road, compiling an invaluable repository of social understanding and practical experiences, in addition to the knowledge of craftsmanship, building, industry and trade, not to mention a wealth of cultural treasures and natural resources.

It would be naive to expect that those who have built their accomplishment with sweat and blood will share it easily with someone who is used to “being spoiled by his mother”. Of course I’m not saying that less “sweat and blood” has been shed in my country (it is sadly right now swimming in pools of it), but the truth is that Syria is a country with enormous human and natural capital, and that makes it relatively easy to accomplish things there, and so it has been targeted by considerable foreign greed. Yes, this country has been misused and misled, and, yes, countless people have been gratuitously wronged. But people don’t lose their homes, their cities, their accomplishments and their identity, as we have done, without themselves being in great part to blame for it. We didn’t lose all that in the final collapse that was aired on TV screens around the world. No, we have been losing it bit by bit long before that.

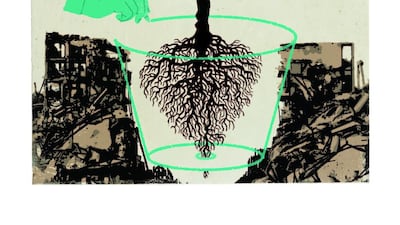

In Syria we have an aphorism: “One who has no old has no new.” I used to look at this as a nostalgic way of attaching oneself to outmoded traditions. Today I think I know better. Since we lost our “points of departure”, we have no longer been able to “orient ourselves towards the world”. All our accomplishments have been erased, starting with the built ones and ending with the living ones.

Our tenets have been shaken and our ground has been destabilised, so no matter how many homes those displaced Syrians try to build outside their country they won’t be able to integrate or feel less alienated. Because they have lost their back, their home and their identity.

Prior to this war, many brilliant young Syrians used to feel obliged to leave a country that oppressed their talents and ambitions through corruption and neglect, but still they struggled day and night to be successful wherever they were so as to buy a home back in Syria.

Although they might not visit for years, they couldn’t accept the idea of being uprooted. Less fortunate young people, meanwhile, remained trapped, scratching the high walls with their fingers in order to climb up and maybe have a home before the end of their lives. All were trying to hold on to a piece of an accomplishment, to grasp even an unravelling thread of their precarious identity, until it all collapsed. One can only wonder why this identity crisis was so prevalent.

And one can only ask: how is our identity to be rebuilt after such massive destruction? On what ground was it standing, and can it be re-established there? And the most important question addressed in my book: what role has architecture to play in all this?

This is an edited extract from The Battle for Home: The Memoir of a Syrian Architect published by Thames & Hudson

Marwa Al Sabouni is an architect based in Homs, Syria, and co-founder of the first and only architectural portal in Arabic, www.arch-news.net