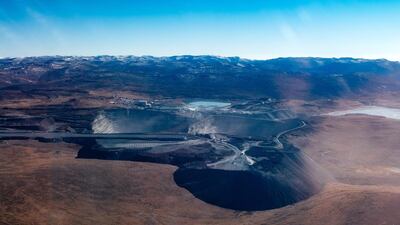

A black and yellow dump truck rumbles up from a giant pit in the mountains of southern Africa, carrying a load of freshly blasted slate-grey rock from the Letseng mine. With luck, it will contain a golf-ball sized diamond worth perhaps US$20 million.

With even more luck, the stone won’t get smashed.

Keeping giant gems intact during the mining process is a challenge for the two companies that account for most of the global production of these multimillion dollar whoppers. They’ve unearthed 15 of the 20 largest diamonds found in the past decade. Almost every one lost a chunk at some point in the process, including the Lesedi La Rona that is the largest found in more than a century.

“Since the time of the caveman mining hasn’t changed much. You pulverise the rock and take out what you want,” said Clifford Elphick, the chief executive of Gem Diamonds.

Gem Diamonds, which operates Letseng in the small kingdom of Lesotho, and Lucara Diamond, which opened its Karowe mine in Botswana in 2012, are in a very different business from De Beers, the world’s biggest producer. With large stones their core business, rather than an unexpected windfall, they’re trying new scanning technologies to reduce accidental breakage.

Back at the mine, Thaabe Letsie watches the truck ascend the opencast pit under a clear winter sky, pauses from directing four drilling machines and says the mining process is a long way from the glamour of the end product. “Somebody is over there in Hollywood or wherever shining with what I produce,” said Mr Letsie, 43. “But something has to start somewhere. It’s not pretty work.”

But it’s thorough. The diamond-bearing rock, known as kimberlite, is drilled, blasted with explosives, hoisted and hauled around the mine and plant and crushed repeatedly to pry the gems from inside rocks that can be up to a metre square in size.

The Letseng mine produces just 1.6 carats of diamond (a carat is 0.2 grams) for every 100 tonnes of rock. The things that makes it worth the hunt at Letseng are the size and quality of its stones. Its average value of US$2,299 per carat is the highest in the industry, according to Gem Diamonds’ earnings released in March. The De Beers diamonds sell for $207 a carat, on average.

The world’s biggest and rarest diamonds have proven to be more resilient than smaller stones. Prices for rough diamonds slumped by 18 per cent last year, the most since the financial crisis in 2008, amid lower demand and an industry-wide credit crunch.

Gem Diamonds resurrected the Letseng mine in 2006 following De Beers, which had closed it in 1982 amid a downturn in diamond prices.

Last year, Gem Diamonds introduced so-called XRT scanners, which can identify loose diamonds from a conveyor belt of rubble and move them to a secure area for processing.

Gem Diamonds is considering introducing XRT scanners earlier in the process, before the mined rocks are crushed, to minimise the risk of breaking them.

The company recovered a dozen diamonds bigger than 100 carats last year, compared with just four in 2012. Still, all its giant gems have had chunks broken off, including a 357 carat rock that sold for $19.3 million last year and this century’s third-biggest stone, the 603 carat Lesotho Promise, unearthed in 2006.

Some of those breaks can be fortuitous. Lucara says that had they not broken a 374-carat chunk off their 1,109-carat stone it would have been crushed to pieces in a plant not designed to take such big stones.

“When people say you broke a 1,500-carat diamond, I say we recovered an 1,100-carat diamond,” said William Lamb, Lucara’s chief executive. “The words ‘mining’ and ‘gentle’ don’t go very well together.”

business@thenational.ae

Follow The National's Business section on Twitter