The Turkish artist Fahrelnissa Zeid made a number of enormous canvases depicting explosive cosmogonies, but one seemed particularly important to her: Towards a Sky, painted in 1953, was one that she kept a picture of by her bedside. But from 1957 to 2012, the whereabouts of this painting were completely unknown.

“The last we had heard it was hanging in the garden of Lord’s Gallery in London,” says Elif Bayoglu, a Sotheby’s consultant who worked on bringing the painting to auction. Then it disappeared.

It re-emerged 55 years later when the owners got in touch with Sotheby’s to discuss a sale. It had been hanging in the corporate collection of an office furniture company in Michigan, its long canvas floating in the atrium of the company’s pyramid-shaped development centre.

“This has been the highlight of my career,” says Bayoglu. “Its size, the intensity of the composition, the vibrancy of the colours – and the fact that it had become a huge mystery.”

The work will go under the hammer at Sotheby’s 20th Middle East sale in April in London with an estimate of £550,000 to £650,000 (Dh2,457m to Dh2,904m). Then, if the new owner agrees, it will go to the Tate Modern in June, where the London museum is mounting a much-anticipated retrospective of the artist’s work. (A true-to-scale reproduction of the artwork is on view at Sotheby’s new exhibition space in Dubai.)

For the canvas, which experts believe Zeid painted in Paris in 1953 before ultimately moving to Jordan in the 1970s – she had married into the royal family there – it has been a rapid ascent from obscurity to international prominence. “They didn’t realise how important it was,” says Bayoglu, referring to the Steelcase furniture company, in whose sizeable collection the painting had hung.

While extraordinary in itself, the sale also highlights the role that the art market plays in bringing to light major works of 20th-century Middle Eastern art. Buoyed by a huge demand for modern Arab, Turkish and Iranian work, auction houses and dealers are racing to uncover still available, lost, or unknown works of the period.

The hunt has been on since the mid-2000s, when 20th-century Middle Eastern art became sought-after on the market side and institutionally. The number of major exhibitions focusing on the work has spiked even in the past five years: the Lebanese sculptor and painter Saloua Raouda Choucair at Tate Modern (2013), the Iranian abstractionist Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian at the Guggenheim in New York (2015), the Lebanese writer and painter Etel Adnan at the Serpentine Galleries in London (2016), the Modernist holdings of Sharjah’s Barjeel Art Foundation at the Whitechapel in London (2015–16), and Egyptian Surrealism at the Centre Pompidou in Paris (2016), to name a recent few.

-------------------------------

The late Saloua Raouda Choucair – a pioneer of abstract art in the Arab world

-------------------------------

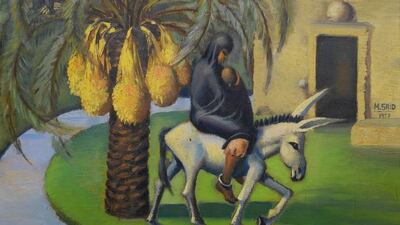

Auction prices are also climbing: a 1962 painting by Zeid, Break of Atom and Vegetal Life, sold for US$2.3 million (Dh8.4m) at Christie's in 2013, while in October last year, Bonhams sold a work by the Egyptian painter Mahmoud Said for £1.2m. These are still short of the incredible amounts commanded by 20th-century western work, but they've risen quickly. And, setting them all into one category of "Middle Eastern" art rather than the predominantly national scenes that existed before, the Gulf has emerged as the centre for their sale: Christie's set up a permanent space in Dubai in 2005, and Bonhams did so in 2008; Sotheby's established a presence in Doha in 2008, and this year in Dubai. The fair Art Dubai, which ends today, was launched in 2007.

“Modern art of this region is not a new ‘discovery’ for the Arab world,” says Salwa Mikdadi, a leading scholar and curator of Arab art and visiting associate professor at New York University Abu Dhabi.

“The art was valued and appreciated by a limited number of people, compared to the interest in the art today. A large number of modern artists were art teachers; they had direct access to the public through education, however, without a market and with few collectors.”

The reasons for the uptick on the market are many: in the Gulf, greater art education and appreciation has led many Arabs to seek out and collect their own art history. From a western perspective, the interest in the Middle East is part of an overdue acknowledgement of the art world beyond Europe and the United States. And the art market overall has experienced a tremendous expansion in the past 25 years.

At the same time, one problem with what auction houses call the “supply” is that there is incomplete information with regards to 20th-century Middle Eastern work. “Unlike the international market,” says Masa Al Kutoubi, a specialist and head of sale at Christie’s, “the Middle Eastern secondary market is still very new and in some ways uncharted territory. There are so many artists we don’t know about because there is not a lot of literature and documentation available. That makes our job – of finding these artworks – even more interesting and relevant.”

While most of the major figures in Arabic art history have already been bought by private collectors or museums, many auction specialists and dealers are doing the kind of primary research into past artists and art scenes that would be typically accomplished by art historians. In some respects, says William Lawrie, who helped establish Christie’s outpost in Dubai and who now co-directs the Dubai gallery Lawrie Shabibi, “the market has raced ahead of academia”.

“We read through whatever books, articles, and catalogues we can get hold of,” explains Al Kutoubi. “We visit a lot of private homes to examine, admire and evaluate collections as well as individual works. Word of mouth is such a strong suit for Arabs and Iranians. There’s a lot of generous and willing sharing of information.”

For families or individuals with suddenly valuable works, auctions are an accessible way to sell them, particularly in a field as closed as the art market. Al Kutoubi, for example, was recently approached by a former Iranian film star, Mary Apick, who has been living in Los Angeles since the Iranian Revolution. Her house in LA became a focal point for the Iranian cultural diaspora, and she is now selling some of the work she acquired during that period. Through this relationship with Apick, Al Kutoubi placed the painting Sahou Fassahah (1984) by Charles Hossein Zenderoudi, an established Iranian artist whose work is now hard to come by, at Christie's where it goes on sale today.

Steelcase, which owned the lost Zeid painting, approached Sotheby’s when they began to deaccession the work, due to the auction house’s history selling the princess’s work. Bayoglu flew out to Steelcase’s headquarters in Grand Rapids to see the painting, and then set to work authenticating it and establishing its provenance. “We knew of the existence of the work because of the photo she kept by her bedside. It was exhibited at the ICA in London in 1954 – it was so tall that they had to roll up one third of the painting,” Bayoglu explains. It was then at Lord’s Gallery in 1957, and Steelcase acquired it in 1987. What happened in the intervening 20 years is still unknown.

The perception of modern Arab art history as unknown territory partly owes to the fact there are few museums where a narrative of the period is publicly visible. The Museum of Modern Egyptian Art in Cairo has a strong collection of Egyptian Modernism – Cairo was the crucible for Arab Modernism – but has not had the resources to properly exhibit its works, and is currently closed. The Sursock Museum in Beirut, which focuses on Lebanese modern and contemporary art, only recently reopened after an eight-year hiatus. The largest collection of Arab 20th-century work is at Mathaf in Doha, which is built around the personal collection of Sheikh Hassan bin Mohamed bin Ali Al Thani (later bequeathed to Qatar Museums), but the vast majority of the work is not on view.

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, who has amassed a major collection of Middle Eastern 20th-century work for his private collection and his Barjeel Art Foundation, has deliberately made his holdings more publicly available, putting images of them online and showing them at other institutions. “Museums and collectors are still reluctant to put their art online for various reasons,” he says. “National archives that may contain interviews with artists have not been digitised and made accessible to the public, making it difficult to conduct research.”

Mikdadi concurs. “The resources are there,” she says. “They are just not digitised.” And while it is roughly true to say that the history of Middle Eastern art is still being written, this discounts major work by scholars such as Mikdadi, Nada Shabout and Silvia Naef. Indeed, largely because of language issues – much is written in Arabic or French – and the need for a fast turnover, there can be a tendency to rely on the scant information that exists online.

Another problem with accessing Middle Eastern art history of the past century is that, because of the wars in the region, many works have been destroyed, and collections dispersed. “So much was lost under the US occupation in Iraq,” says Bahaa Abudaya, formerly a curator at Mathaf who now teaches Arab modern and contemporary art history at the Paris-Sorbonne University Abu Dhabi. Iraq’s national museums were ransacked and many of their works later illegally traded hands. “Now this is happening with works from Egypt,” he continues. “You see a lot coming on to the international market.” Moreover, Abudaya adds, the lack of expertise makes the market more vulnerable to fakes and stolen goods, as few people have the knowledge to authenticate works.

This is another reason why auction houses play an important role: they are a safe bet. "It's a jury of thousands," says Lawrie. For example, in 2015, Christie's offered a version of Jamal Al Mahamel III (Camel of Burdens), a 1973 painting of a man carrying the city of Jerusalem on his back by the Palestinian artist Suleiman Mansour, who made a number of copies of the work. Muammar Qaddafi is said to have bought the second version, from 1975, and that one is believed to have been destroyed in a 1986 US air strike on Libya.

Christie’s listed its version as the earliest available – with a price tag to match – until a collector came forward from London with the original; the Christie’s version was actually from 2005. Christie’s dropped its estimate, along with an announcement saying they were delighted the earliest work had now been found.

“Auctions really bring experts out of the woodwork,” Lawrie says. Though a word of caution: auctions, and the market, can find the works, but can’t contextualise them; there remains a pressing need for proper research done in archives.

Melissa Gronlund is the author of Contemporary Art and Digital Culture (Routledge). She lives in Abu Dhabi.