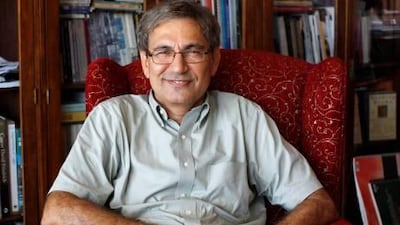

The Turkish Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk is getting closer to completing the real-life version of the "Museum of Innocence", a collection of everyday items described in his novel of the same name.

The book, which came out in 2008, tells the story of a man so obsessed with a married woman that he builds up a huge archive of objects relating to her, from lottery tickets to cigarette stubs, eventually buying her old flat to house them in, and justifying the collection with grand claims. "With my museum," the character says at one point, "I want to teach not just the Turkish people but all the people of the world to take pride in the lives they live."

Pamuk originally intended the launch of the real Museum of Innocence to coincide with the book's release, but according to the latest reports, he's now hoping to open it before the end of this year. Based in the Çukurcuma neighbourhood of Istanbul, it will house 83 wooden boxes, corresponding to each of the book's 83 chapters, containing objects bought or made especially for the museum. As the novel begins in 1975 and takes place over a 30-year period, the collection will not only provide food for thought on the blurry lines between fact and fiction, the nature of obsession and the fruitless attempt to stop time; it will also serve as a history lesson on modern Istanbul.

This isn't the first time a fictional place has become reality. In London, you can drop in on 221B Baker Street, which has been turned into an incarnation of Sherlock Holmes's house as described in the stories of Arthur Conan Doyle. Across town in Holborn, you can browse the Old Curiosity Shop, a 16th-century building that changed its name after Charles Dickens' novel was published, and which maintains a Dickensian air. And at Kings Cross Station you can find Platform 9 outside the building that houses platforms 9 and 10 - it's a reference to the place in the Harry Potter series of books from which the young wizard catches the train to Hogwarts.

While each of these installations is a homage to the work of fiction that inspired them, the Museum of Innocence is different in that it's an extension of the book's fictional world by the author himself. Pamuk told the German broadcaster Deutsche Welle in 2008: "The museum is not an illustration of the novel and the novel is not an explanation of the museum. They are two representations of one single story."

In the same interview, Pamuk admitted he had been collecting objects for the museum for almost six years, and had bought the house he is converting into the museum 10 years ago: he was writing the story and enacting it simultaneously. Perhaps Pamuk's project has less in common with the theme park-style recreations mentioned above, and more in common with what the Scottish artist Peter Hill dubbed "superfiction". Hill created a fictitious "Museum of Contemporary Ideas" in 1989: press releases were sent around the world describing the museum as if it were real and publications printed the story as fact. At a later conference, Hill explained: "I was not trying to create a hoax, rather to reflect a mirror image of the art world. My press releases were testing the art world's ability to tell truth from fiction."

Along with the text for this conference, there is an "Encyclopaedia of Superfiction" on Hill's website, which lists a story by the Argentine novelist Jorge Luis Borges among entries about art world fakeries. The tale tells of an extraordinarily detailed fictional world, snippets of which have been inserted into real (within the context of the story) reference books. Borges fans have run with this idea, inserting references to the world and its language on websites such as Wikipedia. The work encourages the reader to see their most deeply held beliefs in the same light as an elaborate fantasy.

The Museum of Innocence is not intended to be a mistaken for reality, as many superfictions are, but like the characters in Borges' story, it extends a fiction beyond the pages of a book and into the concrete world. The possibilities this suggests for authors in the future, and the ways they could tell stories that envelop real people and real places, are exciting and endless. An admission ticket for the Museum of Innocence is printed inside the novel, along with a map of the building. Talking about these touches in an art magazine interview, Pamuk said: "It was a joy to combine the real with the imaginary."