The true subject of science fiction is always the present. Its imagined futures are mirrors to today's hopes and fears. George Orwell's 1984 simply shifted the numbers of the year in which he wrote the book – 1948 – and made a metaphor of that time's dark politics.

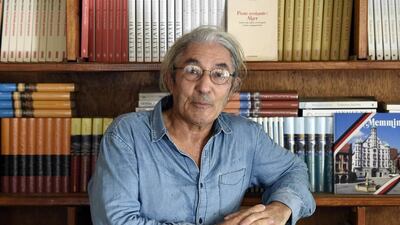

Likewise 2084, the latest from Algerian novelist Boualem Sansal, is addressed to, and in some way is part of, very contemporary woes.

Sansal lays out a fantastically detailed dystopia in complex and often elegant prose. Since the Great Holy War killed hundreds of millions, an absolutist theocracy has been founded by Abi the Delegate, servant of the god Yolah. Abi’s rule is secured by such institutions as the Apparatus and the Ministry of Moral Health, and displayed by frequent mass slaughters of heretics in stadiums built for the purpose. The nine daily prayers are compulsory. Women must cloak themselves in thick “burniqabs”.

Dissent, individuality and progress have been abolished. The future must be a strict replica of the past. All languages are banned save the state-invented “Abilang”.

Ati, the story’s vague hero, is sent to a sanatorium in the mountains to cure his tuberculosis. Here he hears rumours of a nearby border, a limit to Abi’s reign. The notion “that the world might be divided, divisible, and humankind might be multiple” sparks a crisis of doubt in him, and then a journey of discovery.

At times 2084 suffers from science fiction's most common pitfall: an unwieldy listing of technical or political information describing the imagined world outweighs and obscures the necessary human information. Sansal's characters are somewhat two-dimensional, and the plot can seem almost accidental. It is best, therefore, not to read this as a conventional novel but as a mix of satire, fable and polemic.

Abi’s creed – “Acceptance” – has developed from an “inner malfunction” in an ancient religion that “once brought honour and happiness to many great tribes of the deserts and plains”, but was broken by “the use that had been made of it over the centuries ... aggravated by the absence of competent repairmen or attentive guides”. It’s a parody, therefore, not of Islam but of contemporary extremist perversions of Islam. In their melding of religion, calculated barbarism and the totalitarian surveillance state, Abi and his Just Brotherhood are a future incarnation of ISIL.

2084 is a cry against obscurantism and scriptural literalism, a call to dethrone the notion of divinity as an organising principle in society. It is an Enlightenment text which fits in different ways into the tradition of Voltaire (who used the fable genre in Candide) as well as a secularising Arab prose discourse dating back to the late 19th century Nahda (renaissance).

The book is a statement rather than a question; this sometimes gives it the quality of a tract. Its central message – that religious dictatorship is bad while democracy and freedom are good – is somewhat repetitively delivered, and surely no challenge to Sansal’s liberal audience. But in this region, trapped in a vicious circle politically, urgent questions demand to be asked of the liberals. For example: how does the supposed Islamism of the masses become in some eyes an excuse for supporting dictatorship, which in turn nurtures religious extremism?

Strangely, Abi's capital is located not in Raqqa or Algiers, but in a future Paris. (Clues such as a hidden "Louvre" museum suggest so.) This narrative choice makes 2084 the second commercially-successful recent novel – after Michel Houellebecq's Submission – to imagine France under Muslim rule.

In Houellebecq's novel, extremists come to power through elections. In 2084, Abi's System, although nuclear holocausts precede it, seems to have been established by terrorism, "the absolute weapon which one does not need to buy or build, the conflagration of entire populations as they are filled with the violence of terror".

True, France is currently wracked by indiscriminate jihadist-inspired terrorism. Nevertheless, the imminent danger to the polity is not takeover by Islamists (Muslims are 7 per cent of French society, and most are as liberal as their non-Muslim counterparts) but by the Islamophobes and racists of the Front National.

2084 won the French Academy Grand Prize and was listed for at least seven other literary awards. Could this adulation result from the fact that it is easy reading, ideologically-speaking?

This is not to deny the novel's obvious strengths. Flawed it may be, but 2084 is always intriguing, and at its best when it strays off topic into observations on transience, for instance, or into sensuous lists, and long, ludic sentences. Sansal's playfulness is his most endearing writerly quality.

Robin Yassin-Kassab is a critic, novelist and the co-author of Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War (Pluto).