You'll know a Kobra mural when you see one. Kaleidoscopic, larger-than-life with harlequin patterns often woven in with portraits of people, some famous, others less so – this is the Brazilian artist's signature style.

His latest, and one of his largest works to date, bears all these elements, and it can be found right here in the UAE. Titled Tolerance (Tolerancia), the near-2,000-square-metre work stands out in Al Bateen, Abu Dhabi, where it envelops one of the district's buildings.

A self-described “street art soldier”, Eduardo Kobra is one of the most well-known graffiti artists in the world. His murals, of which there are thousands, have been showcased in more than 40 countries across five continents. He has a huge online fan base, too, with nearly a million followers on Instagram.

Born in the outskirts of Sao Paulo, Kobra started graffiti when he was 12 years old. But these works were not the vibrant and hyperreal visuals we know today. Back then, he was mainly into tagging, impulsively leaving his spray-painted signature across the city. He would often get into trouble for this, receiving warnings from his school and facing arrest for vandalism.

Now, at 44, he is being commissioned around the world to create his murals, and his work in Abu Dhabi is one of them. It is part of the Department of Municipalities and Transport's For Abu Dhabi initiative, which was developed with the goal of beautifying the capital's urban spaces and strengthening its liveability.

Among the number of public revamps planned as part of the drive, a series of street art projects is on the list. Over the next few months, artists including Elian Chali, MadC and Tarsila Schubert will be painting and drawing all over the city's walls.

Kobra's mural is inspired by an earlier campaign by the Department of Community Development called This Is Abu Dhabi. Featuring black and white portraits of people from different backgrounds, ethnicities and age groups, the images sought to highlight the city's diverse population. When Kobra saw this campaign online, he felt it resonated with his own ethos. "It is already part of my work to speak about peace and tolerance, about different cultures, ethnicities and traditions. This is a continuation of that," he tells The National.

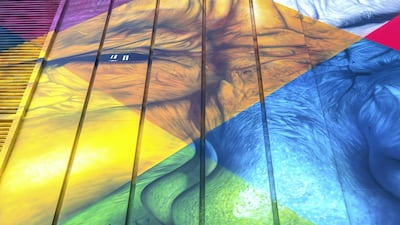

For example, his mural, The Ethnicities (Las Etnias), for the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro in 2016 celebrated indigenous groups from five continents, including the Huli (New Guinea), Kayin (Thailand and Myanmar) and Tapajo (South America) peoples. These portraits, stretched across an area of almost 3,000 square metres along the city's port, seem to appear through rainbow-tinted screens – Kobra typically paints his subjects in a photorealistic fashion, while the overlapping colours turn them into dreamlike visions.

The same effect is done in Tolerance, with the artist placing half-portraits side by side. From afar, the individuals seem to fuse together, a young Emirati boy's face blends into that of an older western woman, while an African girl and South Asian man appear "stitched" together by bright diamond shapes. Kobra used a similar technique for his older works, such as in his mural of artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, in New York. The two, who shared a complex and tumultuous relationship, appear as one.

Kobra also highlights cultural and historical figures in his work, including Martin Luther King, Albert Einstein, Mahatma Gandhi, Mother Teresa and Nelson Mandela. Typically, he tries to choose subjects who are most relevant to the area and the communities who will live with the work, such as his three-storey painting of Louis Armstrong in New Orleans, where the jazz musician was born and raised.

Though he's known for his use of colour now, the artist didn't always paint in his kaleidoscopic style. He made his name with his Wall of Memories project, where he translated 1950s photographs and postcards of Sao Paulo on to the city's walls in sepia and monochrome. Soon, he started to colourise these murals, as you would a photograph in Photoshop, and later he developed his distinct, vibrant palette. "I'm a self-taught artist," he says. "It's been my career for over 30 years, non-stop. I've always been very determined, persevering and experimenting."

With his success, Kobra's days of warning slips and hurried tagging on the streets are long over. He works with a team and is able to spend time perfecting his murals. On the ground, Tolerance took almost four weeks to complete, with the help of his two most-trusted assistants. His process involves long periods of planning, which includes considering the building's structure, sketching out the visuals and dealing with site-specific adjustments later on.

Have these sanctioned and big production projects made graffiti lose its edge? Kobra doesn't think so. "The fact of whether an art is legal or illegal doesn't make it good or bad. It's not an issue of judgment," he says. "What I try to do is use these invitations and ensure that they're in line with my convictions, my artistic vision, the idea of connection, tolerance, peace. As an artist, this is my ultimate objective."

He says graffiti art need not be seen as purely belonging to the street, citing legendary figures such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, who both started out as graffiti artists and eventually made their way into prestigious galleries.

"This transition is not new. I'm not the only one doing it," says Kobra. "The problem is when the artist stops doing what they believe in for money. You need sponsorship to exist, and I needed a sponsor for Tolerance to be realised."

Outside of his commissioned projects, Kobra wants to bring art education to communities in Sao Paulo. He has recently received approval to set up an arts centre in the city, where underprivileged children can learn drawing, painting and other forms of art. Having grown up relying on himself and his own grit to make it, he says he wants to give budding talents the opportunities he didn't have. "I see myself in them."