Children's books can be scary. Roald Dahl's The Minpins, with its nasty creatures, such as the Spittler and the Gruncher, lurking in the forest, terrified me. It still does, really. For other people, perhaps it was Maurice Sendak's Where the Wild Things Are or Mercer Mayer's There's a Nightmare in My Closet.

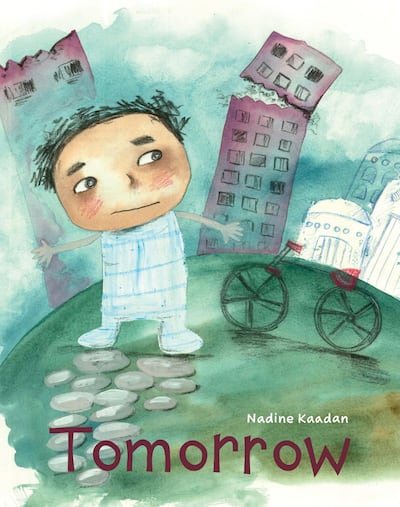

Syrian author Nadine Kaadan's Tomorrow is unsettling for entirely different reasons. Her words and illustrations do not conjure up elaborate monsters or spooky goings-on; instead, they depict the very real concerns of a young Syrian boy called Yazan, who is no longer allowed to go to the park. He's not quite sure why but, as Kaadan writes, "Everything around him was changing."

'Children’s books are the best way to introduce any sensitive topic'

In a note on the final page of Tomorrow, which was published in 2012 but translated from Arabic into English earlier this year, Kaadan adds: "The situation continues to worsen for Syrian children, especially those who are living away from their homes and who have missed years of school. Today, we wait for a time when 'tomorrow' can be a better day for all Syrian children."

Tomorrow represented a significant departure for Kaadan, 33, who has published more than 15 children's books. The dreamy, rainbow-like watercolours that smudge the pages of her other books were here replaced by a grey, foreboding palette. This shift was unexpected. "I didn't think that a style [of painting] could change so quickly," she says. "The war in Syria proved me wrong. The shock of what was going on must really have affected my personality and infected my mood."

Tomorrow does have a happy ending of sorts. Yazan's mother paints a park on the walls of her son's bedroom featuring "everything you've ever dreamed of". The book, for all its ominous implications, will still delight young children – there are bicycles and paper planes and annoying parents. But the impact of the war is what stays with you, the broken buildings, the falling debris, the worried faces. It is a radical, courageous thing for Kaadan to have created.

"I've always believed that children are smart enough and curious enough to not hide anything from them," she says. "Children's books are the best way to introduce any sensitive topic. It is important for [Syrian] children to see their story in a book, to open up the conversation. It helps them to know that many children are going through what they are going through and that they are not alone."

What children can learn from in the English translation

But what about the children reading Tomorrow in English? How have they responded to a war they may know nothing about? "The first time I read it aloud in the UK, I was very nervous," says Kaadan. "What was interesting, though, was that they were able to relate on a personal level. The sadness and the anxiety of the little boy [in Tomorrow] is something all kids can learn from."

Kaadan then tells me a story about a little girl who came up to her after the reading and announced that she, too, had been through the same thing as Yazan. “I said, ‘Really? How come, you live in the UK?’ She replied, ‘Well, we wanted to go to the park and it was raining and I got stuck at home all day and I felt so sad, just like him in the story.’ It was really beautiful to see this connection.”

'Damascus is just a magical city'

Kaadan was born in Paris in 1985, but grew up in Damascus. Her mother taught French literature and Kaadan and her sister, who is now a filmmaker, were raised in a liberal environment, encouraged by their parents to have a go at everything.

When Kaadan was eight years old, her mother bought her a set of paints. The shopkeeper kept telling her: "[Those are] for professional artists, not children." To which Kaadan's mother replied, "Well, that's what she'll be one day." The author wrote and illustrated her first story soon after and began producing a children's magazine, which she photocopied and distributed at her school.

She went on to study fine art at university in Damascus and in 2012, following the start of the war, moved to London. There, she studied for an MA in illustration at Kingston University and an MA in Art and Politics at Goldsmiths.

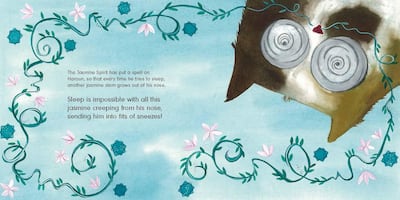

Kaadan still lives in London today, but it is her memories of growing up in Damascus that have inspired her books, including the irresistible tale, The Jasmine Sneeze. Published in English in 2016, it follows Haroun, "the happiest cat in the world", who has one problem: the smell of jasmine makes him sneeze so much that he can't sleep. The colours are rich – inky blues and sunrise pinks offset great puffy balls of white – and the tone is bouncy and joyous. It is a love letter, really, to her home country.

“Damascus is just a magical city,” says Kaadan. “I would be surprised if an artist lived there and wasn’t inspired. I spent my childhood playing in the courtyards, running after pigeons or enjoying the magnificent architecture.”

Her love for the Syrian capital is infectious, The Jasmine Sneeze a visual hullabaloo, which, Kaadan says, children love because "suddenly Syria is not just war and conflict". In many ways, The Jasmine Sneeze is Kaadan's counterbalance to Tomorrow. "When [western] kids meet a child who is a refugee from Syria, then their interaction will be different just from this one story," she said in an interview last year. Her next book will surely have the same effect. Due to be published in 2020, Bassel & Stella tells the story of a Syrian refugee trying to reunite with his dog.

'Have you ever seen someone in the Arab world sitting and reading a book?'

We have all experienced the hit-and-miss nature of giving a child a gift – an expensive toy discarded for the wrapping paper. How does Kaadan know if her characters will entertain children? "I always question myself during the creative process," she says. "Is it going to be interesting? Are kids going to relate to it? If I love the story and it makes me laugh, it will make children laugh."

The reading habits of people in Kaadan’s home country and across the Middle East, however, mean that a worryingly small number of children will ever experience this. “It is a catastrophe,” she says. “First of all, have you ever seen someone in the Arab world sitting and reading a book? We don’t have that culture unfortunately and children don’t grow up watching their parents read.”

_________________

Read more:

Netflix to adapt Roald Dahl classics to small screen

The Emirati engineer who became an author, and then started a publishing house

A new children's book character introduces the community to Emirati tales

_________________

Added to this, for many people in places such as Syria, children's books are just too expensive. "How many can buy a picture book that costs $10 [Dh36]?" says Kaadan. "One of the problems is that reading is [perceived as being] for the elite." Although there are an increasing number of publishing houses specialising in Arabic children's books, Kaadan concedes that "she doesn't have the answer".

The situation is so dispiriting because it is in books such as Kaadan’s that children in the Arab world will see people and places they recognise. “When my books are distributed [for free], I see the reaction of the children,” says Kaadan. “It helps them to relate.”

They need these books now more than ever.

Tomorrow and The Jasmine Sneeze are published by Lantana